Julian Drinkall took on the biggest trust turnaround job going. Here he talks about constraints, innovation, bravery – and why he removed every single chair of governors

Julian Drinkall, departing chief executive of Academies Enterprise Trust, was asked to hurry the heck up and start his post early. He was scheduled to begin in March 2017, and instead was told by the Department for Education to get into the trust for December.

“I literally stepped red-eyed off a plane from New York […] I walked into Sanctuary Buildings and got a bollocking. They said it was an absolute shambles,” he tells me, referring to the then-failing trust, the biggest in the country and a terribly awkward symbol for the government’s flagship academisation policy. “I thought, I’ve got to get in fast – this thing could collapse.”

Drinkall was leaving a seemingly different world behind him. As CEO of private schools chain Alpha Group, he’d just been in Manhattan opening a school based on one in London that has Princes William and Harry as alumni. Now he was taking on a trust widely regarded as having taken on too many struggling schools in the most deprived areas of England, too fast.

Nor was he a straightforward educationalist. His CV is a crash course in change-making at big organisations before moving on. Highlights include head of financial and commercial strategy for the BBC for three years; a director of strategy at Boots for two years; CEO at Macmillan, the education publishers, for three years; and at Alpha for two and a half years. It will be four and a half years when he steps down at the end of this year – AET has demanded his attention.

Drinkall is heading off to lead Aga Khan Schools, part of Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), which works across Asia and Africa. He will oversee 250 schools and wants to turn it into a “super global education agency”.

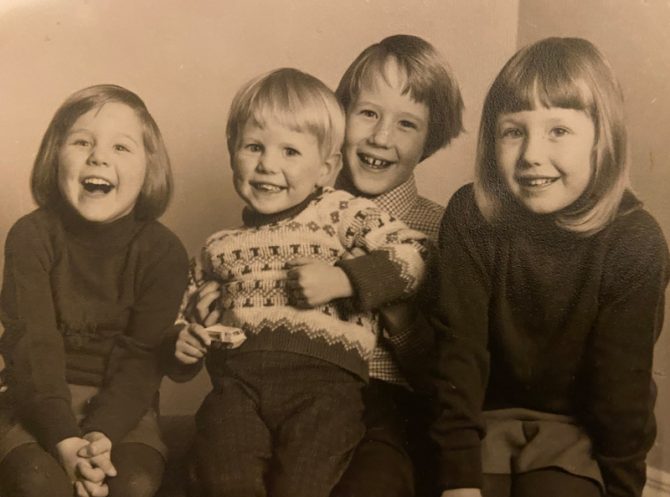

With parents in the Foreign Office, Drinkall has the kind of restless-yet-focused, horizon-scanning energy of someone who’s not spent their entire professional life in England. His mother was born in Morocco, his father in Myanmar, his two sisters in Cyprus and his brother in Brussels, and he, the odd one out, in London. Having seen plenty of continents and contexts, he talks, talks, talks – ideas and stories spill out from him. Given this, it’s surprising in some ways Drinkall hasn’t had a bigger national profile as a mega-MAT leader. But in other ways, it makes sense – it’s not a system he appears hugely impressed by, or desperate to ingratiate himself with.

“I don’t think we’re terribly bold about education in this country,” he explains. “For me personally, I’ve felt very constrained… I don’t think there’s enough boldness, innovation, R&D, trying to do new things. There’s not enough value placed around practitioners, teachers and educationalists, and I worry because the sector is backward when it comes to finance, HR, technology. I think the whole thing is quite conservative. It’s wrapped up in its own language.”

Perhaps only someone with this kind of relish for dismissing creaking, ineffective approaches would have dared to take on AET in 2016. It could have been career-ending. An Ofsted trust-wide inspection in 2014 to then-chief executive Ian Comfort said progress at all phases was below national levels and disadvantaged pupils were “well behind” their more affluent peers. By 2016, another inspection warned only 59 per cent of academies were ‘good’ or better, with eight schools having actually got worse since joining. The trust had been banned from taking on new schools and 90 per cent of schools were operating deficits.

Drinkall moved fast. “I changed the whole management team, just one person stayed. I found a lot of smart, clever, junior people and I elevated them to the top table. A lot of the old deadwood, they went. The finances were horrible, and the local governing bodies were awful.”

I found a lot of smart, clever, junior people and I elevated them to the top table

Here Drinkall made his first more controversial decision: The Times quoted him as saying “playground bully parents” would no longer be allowed to sit on school governing bodies. Instead, only people with expertise in education would. The National Governance Association said removing parent governors was an “own goal”; but, undeterred, Drinkall had removed all 64 chairs of governors by his seventh month in post. “That allowed us to exercise more control of the schools. It meant we had a management team doing school improvement, and a governance team making sure that school improvement was landing.”

Parental engagement is important, he says, but governors who aren’t educationalists don’t always act in the best interest of a school. For instance, when the trust was allowed to accept a primary school in Essex in 2018 (its first new school in five years), “the governing body only agreed because the parents and staff put so much pressure on them that the old bufter-tufters had to agree”.

A hugely energetic and engaging streak in Drinkall must have helped him get away with it – he can carry people with him. With educators on his governing bodies, he now persuaded some of the biggest names in education to the top table. It reads like an edu-royalty list: last year, former national schools commissioner Sir David Carter became a trustee, as did Jane Ramsey, with a background in health and care and wife of former permanent secretary to the DfE, Jonathan Slater; Adam Boddison, national special educational needs leader; and Professor Becky Francis, CEO of the Education Endowment Foundation. They joined Matthew Purves, deputy director at Ofsted for curriculum.

Drinkall also managed to persuade the biggest heavyweights: the DfE. “The DfE used to send a person to every single board meeting, they didn’t trust us an inch, and we managed to get them off us after a year,” he chuckles. He’d presented then national schools commissioner Carter and then academies minister Lord Nash with a five-year plan, which had cut the mustard.

By April 2019, the ESFA had agreed to provide up to £16.1 million to the trust. To MPs’ great annoyance, ministers wouldn’t say exactly how it would be spent. Lucy Powell on the education select committee pointed out for local authority schools, “it would be forced academies like that [she clicked her fingers]. There would be no turnaround time, no cash injection.”

With the mob baying, next month the education unions accused Drinkall of failing to listen to staff over proposed restructuring, and called for a motion of no confidence in the trust. The 2017 accounts show £2.5 million was spent on staff restructuring costs and £1.4 million last year. At the same time, staff numbers fell from 6,380 in 2017 to 4,962 last year. Meanwhile, Drinkall’s salary was £285,000-£290,000.

However, the vote of no confidence was called off – likely because many of the changes were working.

“We didn’t draw down half the amount,” he says of the ESFA cash injection, adding the actual loan drawdown came to £5.7 million, a “good value offer” given the crisis his team averted. The accounts show a £1.4 million operational surplus and no in-year deficits.

Meanwhile, 72 per cent of academies are ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’, up from the 59 per cent in 2016. Not every measure is mindblowing: three schools are still inadequate, and the progress 8 score across the trust remains just below average at -0.33.

But perhaps this is why Drinkall is interesting: he didn’t pour all his energies into boosting government-sought scores. He appears to genuinely want his students and staff to look into the outside world, like he does. The trust launched an unusual goal: for every child to “choose a Remarkable Life.”

“I’m keen on traditional education measures, but I’m much more interested in, where are our children going?” he says with force. He’s brought in careers expert Ryan Gibson, who helped implement the Gatsby benchmarks, and wants destinations data on alumni collected. There are weekly “pulse” surveys of staff to gauge job satisfaction, which once only ten per cent used to fill out but now two-thirds do so, he says.

So many school leaders play it by the book. The obsession with the rules, it’s ridiculous

In a way, the AET story, through Drinkall, reveals a few things. First, any schools can probably improve if you bring in a brilliant thought-leader, the best minds in education and a cash injection: in other words, if the DfE is keen to save you.

Secondly, the system itself remains too constrained to keep someone as interesting and internationalist as Drinkall. He’s off to Geneva, to headquarters beside the World Bank and the United Nations.

“Many school leaders here, so many of them play it by the book,” he says. “The obsession with the rules, it’s ridiculous.

“Education is old as humanity, and most of the rules have only come from the last ten years. We should remember that.”

Your thoughts