England’s largest school management information system (MIS) provider is “radically” cutting prices and undercutting long-standing local authority partners in a fresh bid to stop schools ditching it.

Schools Week can also reveal that Education Software Solutions (ESS) suffered a write-down of £36 million on an abandoned version of SIMS – and how this contributed to controversial contract changes widely seen to have fuelled a record exodus of schools last year.

Experts and trust leaders say schools now have more choice of systems than ever. But they have also become “bystanders in a turf war” between suppliers, which is spilling into legal battles and sparking regulator intervention.

MIS = SIMS

For decades, management information systems (MIS), sometimes called the “backbone” of schools, have been near-synonymous with School Information Management System (SIMS).

Developed by Bedfordshire teacher Phil Neal in the 1980s, SIMS was the first software to collate all pupil data, and its obvious value saw it quickly spread.

Outsourcing giant Capita bought the company in 1994, and SIMS has remained the most popular pupil and staff data platform since. ParentPay Group has owned it since 2021.

The market was “stagnant for decades”, according to one trust leader, although Neal told Schools Week many companies “tried to break into it but didn’t succeed”.

Neal claimed it once benefited from local authorities not “going out to tender when they should have”. They appreciated SIMS’ benefits, and baulked at full procurement given high costs and few alternative suppliers.

In 2012, 18,051 English state schools – 84 per cent – were using SIMS, analysis of DfE data suggests.

Market shake-up

A decade on, the market has been “shaken up”, according to Joshua Perry, an edtech entrepreneur who runs the MIS blog Bring More Data.

By last autumn, ESS was used in about 12,281 schools, meaning it now holds 56 per cent of the market, official data obtained by Perry shows.

Arbor, another MIS provider that launched in 2011, now boasts 3,500 schools.

James Weatherill, its chief executive, said cloud-based alternatives emerged just as academisation was encouraging schools to review council-negotiated deals.

Covid fuelled further demand for cloud products, offering remote access when staff could otherwise only access data via on-site servers.

Arbor said teachers and leaders found its systems intuitive and easy-to-use.

Meanwhile Ali Guryel, the founder of another fast-growing challenger, Bromcom, attributed its expansion to “comprehensive functionality” and cost savings too.

A recent poll suggested three-fifths of UK schools now have at least partly cloud-based systems.

£36 million write-down of ‘shelved’ SIMS 8

ESS has launched cloud services, but only 40 per cent of its schools use them, despite Capita unveiling a “next-generation, cloud-based” MIS five years ago.

ParentPay Group also said in 2020 that its looming takeover would “accelerate innovation…including the roll-out of ESS’s cloud-native SIMS 8”. The current version is SIMS 7.

But new ESS documents show a review under Montagu Private Equity, which briefly owned ESS in 2021 before it joined ParentPay Group, found “significant issues with the technological feasibility” of SIMS 8 – reportedly making it “not commercially feasible” by late 2020.

Developer Neal called it a “great shame”, saying he’d hoped it would take SIMS “to the next level”. He left in 2017, and said he even advised some organisations not to buy the company he started.

SIMS 8’s stated value was slashed by more than £36 million and the latest accounts highlight its “retirement”, removing it from balance sheets altogether.

ESS halted investment, deciding to “instead invest in a new cloud proposition”. It subsequently pledged £40 million towards SIMS Next Gen, with some features released last year.

In October ParentPay also appointed Lewis Alcraft as chief executive.

He said the decision to shelve SIMS 8 was “correct”. ParentPay instead would use its experience developing cloud-hosted, SIMS-integrated applications to offer “a raft of functionality” due via Next Gen this year.”

‘Whoever steals a march could be new SIMS’

But Duncan Baldwin, a former headteacher and SIMS employee who now works as a consultant, said the “hanging question” was: “Will they get it right next time?”

One trust leader told Schools Week the pace of ESS’ cloud rollout had allowed rivals to pounce, but they only had a “narrow window” given ESS’ three-year Next Gen investment.

“Whichever rival steals a march could position themselves as the new SIMS.”

Perry agreed there was “something of a gold rush”, estimating schools spent up to £200 million annually on MIS.

ESS recorded profits of £22.4 million in 2021, and its sale netted Capita £343.5 million.

The Key Group plans to buy ESS’ competitor RM’s Integris and finance businesses for up to £16 million this year, after buying Arbor for £28.1 million in 2020 and another rival ScholarPack for £13.2 million in 2018.

But the trust source said changes to the market had made schools “innocent bystanders in a turf war”.

Three-year deal controversy

ESS itself sparked major controversy in late 2021 over its handling of a move from one- to three-year contracts.

The company said it needed “certainty of revenues” for SIMS Next Gen, which in turn was vital if it were to compete and meet demand.

But hundreds of schools sought to take legal action, and the CMA launched an investigation.

The watchdog’s preliminary finding in November was that ESS “unilaterally” imposed “unfair terms”, with regulators not persuaded that the investment required justified the “limited opportunity” for schools to switch.

ESS maintained its conduct was not anti-competitive, but the CMA closed the case without ruling either way after ESS offered further extended break clauses. Schools have until Friday to apply to adjudicators.

ESS undercuts partners

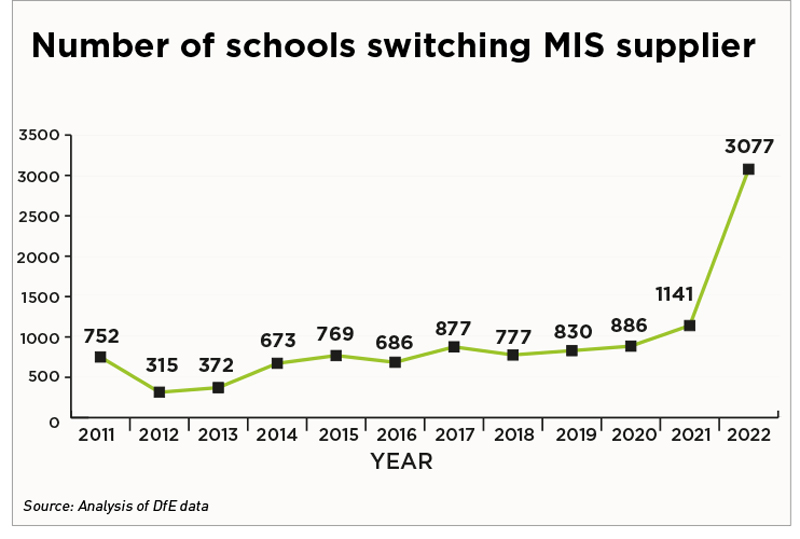

ESS told adjudicators last month that “large numbers…were able to switch”, acknowledging up to 3,000 schools abandoned SIMS within a year.

Documents reveal “the loss rate occasioned by the move…was on a monthly basis over six times the rate experienced in the previous three years”.

ESS is now trying further tactics to stem the tide.

In the 2000s, a government review found its licensing costs had roughly trebled in three years.

But a December letter seen by Schools Week offered some customers a 16 per cent price cut on SIMS, and said it would “radically reduce” in-house support costs to almost half of the prices offered by so-called “SIMS support units”.

The company once encouraged councils to launch these units. Many still run them, although some have been spun off.

Alcroft said he expected attractive pricing to win over “many more schools”, and “we very much hope” support units would match or even better ESS prices.

But Somerset County Council dubbed this “another sudden and significant change”. A spokesperson said it was “exploring the implications”.

One support unit employee questioned how ESS could afford to cut costs, and how units would survive if many schools moved to SIMS’s in-house support.

Fears of fresh legal battles

The “turf war” has also reached the courts. Bromcom recently sued United Learning and Academies Enterprise Trust over deals with Arbor.

The AET case is ongoing, but a judge last month said United Learning breached procurement law and he would award Bromcom damages.

Guryel said Bromcom sued to promote “best practice”, but United Learning hopes to appeal, warning that other schools risked “repeated litigation”.

Paul Wareing, who once worked at the defunct government edtech body Becta, said the organisation could have provided guidance and limited this risk had it not been culled in the 2010 “bonfire of the quangos”.

ESS: Competition ‘keeps us focused’

Alcraft noted new entrants to the market were launching “all the time”, and welcomed increased competition that “keeps us focused”.

He said some schools had even returned to SIMS as they had “not been able to get rich functionality” elsewhere.

He said SIMS offered an “unrivalled range” of products via partners. Any rival attempting to offer everything themselves risked doing things “not very well”.

A Department for Education spokesperson highlighted DfE guidance and information on choosing MIS suppliers, and said schools should conduct “due diligence” on suppliers, follow their legal obligations and “get the best value”. But they added: “The decision is ultimately one that sits with schools.”

Ultimately, as Baldwin noted, “the market will decide”.

Your thoughts