The number of surplus primary school places is set to soar by up to 140 per cent in some areas of England as the population bulge created by the 2000s baby boom moves into secondaries.

Councils are already reducing school capacity, with empty classrooms being repurposed into SEND units. Staff cuts are also expected.

The number of primary and nursery-aged pupils in England is projected to fall by around 300,000 over the next five years (6.5 per cent), from about 4.6 million this year to 4.3 million in 2026.

We know that in certain parts of the country, including in some inner-cities, this is already beginning to have an effect on school budgets

However, objections from parents forced councillors in Brighton to shelve controversial plans to reduce the published admission number (PAN) of seven schools, showing the difficult task faced by decision-makers.

To complicate things, councils only oversee admissions for maintained schools. Academy trusts are their own admissions authorities. About four in ten primary schools are academies.

‘Falling numbers already impacting budgets’

James Bowen, the director of policy at the leaders’ union NAHT, said falling pupil numbers were “certainly a concern” for heads.

In some inner-city areas, this was “already beginning to have an effect on school budgets”.

But he said that rather than allowing primary school budgets to contract, the government should maintain funding so that schools could maintain existing staffing levels and provide “smaller class sizes and more targeted support for pupils”.

All councils have some surplus places to deal with unexpected influxes. But large surpluses cause financial problems for schools.

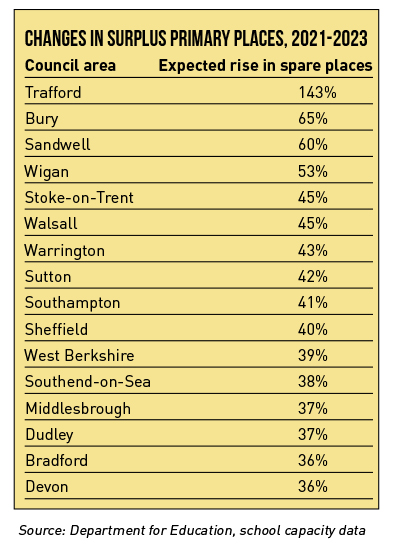

Government data shows more than two thirds of council areas face an increase in surplus places over the next two years. Schools Week approached the 23 local authorities that expected rises of more than 30 per cent.

Fewer staff and repurpose empty classrooms

Middlesbrough said it expected schools to “find it necessary to employ fewer teaching and support staff” over the next eight years.

The council is also exploring alternative uses for primary school accommodation, including SEND units.

In Luton, admissions numbers have been reduced at six schools and a further two are consulting on the change. The council said it was “likely” more reductions would follow.

Southend council has a “primary school reduction plan”, and the capacity of seven academies and one maintained school has already been reduced by 270 places.

And Walsall Council said it would be “undertaking conversations with primary schools in the spring term of 2022 to look at the impact of reducing demands”.

Nottingham is also reviewing its primary surplus capacity, but said closing schools was “not a favourable option” because the pupil population was likely to grow again.

West Berkshire council said it kept admission numbers under review, “and have reduced some, in agreement with schools”.

“Natural wastage” was the most common way to lose staff, it said.

Protestors force council to shelve admission cuts

However, Brighton councillors recently abandoned plans to cut the PANs of seven primary schools from 2023.

The city faces a 24 per cent increase in surplus places in the next two years.

Campaigners argued that the proposals disproportionately affected smaller schools in disadvantaged areas, after attempts to downsize four larger schools were thrown out by the Office of the Schools Adjudicator last year.

Leila Erin-Jenkins, a campaign organiser, said the “burden of the cuts needs to be distributed across the city”.

Councillor Zoe John said decisions from the OSA left the council working “with our hands tied behind our backs”.

Academy trusts also face tough decisions. The Elliot Foundation academy trust has had to close one school and reduce the PANs of several others in recent years.

Chief executive Hugh Greenway said the decline in pupil numbers “has been coming for some time”.

“If you don’t reduce the PAN, you get forced into a position where you have to maintain staff in a school that you don’t have funding to support. You burn through reserves maintaining staff for children who might join you in-year.”

The Reach2 Academy Trust said it too had reduced a “small handful” of PANs in areas where there had been a “significant reduction” in the birth rate.

“But overall across the trust we have seen an increase in our pupil numbers.”

Surplus spaces for housing boom

In some areas, rises are a result of planning for rises in pupil numbers.

In Trafford, the number of spare primary places is due to rise by 143 per cent between this year and 2023-24.

A spokesperson said surplus places were needed to “accommodate the large numbers of families who move into our area during the school year”.

The council is also expanding some schools to create additional places from next year.

Bury’s surplus places will rise 65 per cent. A spokesperson said the picture was “complicated”, with some schools more affected than others. They also pointed to “high demand” from outside the borough, and plans for “thousands of new homes”.

Sandwell, in the West Midlands, is facing a 60 per cent rise. But the council’s predicts an overall 5 per cent surplus across the primary school estate”.

It said some schools “may choose to make redundancies”, but surplus space would initially be used to expand key stage 2 provision.

The DfE said councils should be “reducing or re-purposing high levels of spare capacity”, in order to “avoid undermining the educational offer or financial viability of schools in their area”.

Town halls can also set aside some schools funding for “falling rolls funds” to support schools that need to maintain surplus places.

I know this is stating the obvious, but in the current situation for primary schools it’s vital now that they listen to their community and make sure they stand out from others so parents choose them. Once schools start being known as not full there’s often a knock-on effect and major consequences. And a top OFSTED rating isn’t enough. A real challenge at a difficult time.