A government crackdown has revealed the extent of financial mismanagement, deficits and fraud among maintained schools nationwide.

More than one in three councils reported school funding fraud over two years, and eight councils stripped schools of budget powers because of financial issues in 2020-21.

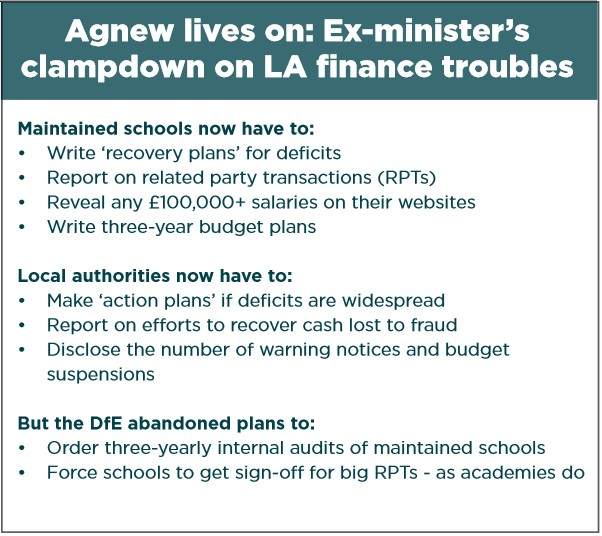

Schools Week has seen data that local authorities are now forced to hand over to central government following ex-academies minister Lord Agnew’s crusade to bring transparency and accountability in line with academy rules.

Yet some experts suggest the Department for Education should go further, claiming controls remain weaker than for academies.

Ghost of ministers past

A “clampdown” on academy financial mismanagement – triggered by multiple high-profile scandals – has been extended to maintained schools, with the DfE saying it had now fully implemented Agnew’s reforms.

Local authorities have to disclose dedicated schools grant (DSG) fraud reports and any interventions over financial challenges.

Those figures, obtained by Schools Week, provide some of the most detailed national data yet on maintained school finances.

They show more than a third of councils (58) reported fraud involving day-to-day school funding between 2019 and 2021. The 185 fraud cases totalled £2.4 million.

Cheshire and West Chester schools had the most cases (32), while Buckinghamshire saw the highest-value estimated losses at £1.51 million.

Separate figures show the government received less than half as many fraud and irregularity allegations (71) involving academies over the same period – despite them educating more pupils. Confirmed fraud, irregularity and theft totalled £2.1 million.

LA controls ‘weaker’

Andi Brown, co-founder of consultancy SAAF Education, said current controls over maintained schools varied by authority but were “significantly weaker” than academies, with regular audits less common.

Multi-academy trusts typically applied “more scrutiny” and had greater financial expertise because of their accounting and auditing duties, size and budget powers.

While many early academies “fell foul” of unfamiliar funding rules, restrictions have since tightened. Regulators recently praised a more “mature” sector, and an ongoing review could even loosen requirements on trusts.

Trusts also still typically face greater transparency over financial problems, with detailed accounts and any government “notices to improve” published online. Thirty-nine trusts received such notices in 2021.

Councils only publish authority-wide accounts and do not routinely publish their similar school warning notices.

Some schools stripped of budget powers

Twenty-six authorities issued 94 notices in 2020-21 for schools not meeting funding rules. These are similar to academy improvement notices, also issued when funding rules are breached.

However, each council sets its own rules on finances and intervention, whereas the government sets academy rules nationally – and academy notices only relate to trusts, not individual schools.

On council notices, Liverpool issued the most (18). Eight councils even stripped 23 boards of budget powers.

Meanwhile, more than two-thirds (109) of councils ordered at least one school to write “recovery plans” to tackle deficits, another Agnew-initiated requirement. More than one in five (34) had 10 or more schools on such plans.

But Brown said suspension levels were “tiny” and that several high-deficit schools were not stripped of powers. Guidance says substantial or persistent rule breaches can trigger suspensions.

‘Greater scrutiny’ needed

The DfE ditched further reforms in 2020 to mandate three-yearly maintained school audits, however.

This was despite Schools Week having revealed in 2018 that 2,200 maintained schools were not audited for more than five years.

Brown said “greater scrutiny” was needed – potentially through a planned scrutiny and transparency drive by the new “Office for Local Government”.

Trust chiefs have previously suggested councils’ interventions amounted to marking their own homework. One trust leader said all schools needed “the same regulatory rules and high standards”.

Steve Edmonds, director of advice at the National Governance Association (NGA), said boards should “prioritise obtaining capacity” to oversee finances effectively. The NGA supports “the principle of intervention” where necessary.

Julia Harnden, a funding specialist at the school leaders’ union ASCL, said the “vast majority” of schools were well-run. Council controls “should be regarded as sufficient unless there’s clear evidence to the contrary”.

Councillor Louise Gittin, the Local Government Association’s spokesperson on children, also said schools and councils needed extra support amid soaring costs.

Super-head pursued over lost cash

The figures come in the same week school business manager Debra Poole was convicted of abusing her former position at Hinchley Wood Primary School in Surrey by stealing more than £490,000. She was found guilty of four counts of fraud.

Surrey Police detective constable Lloyd Ives said her “elaborate deception…afforded her luxury holidays and cars”, but the conviction showed criminals they would “get found out”.

A Surrey council spokesperson said it had supported the since-academised, now-“thriving” school and welcomed the verdict, but added: “Wrongdoing went undetected for too long”.

Meanwhile Dudley is currently seeking to recover funds after David Bishop-Rowe, a former special school “super-head”, was jailed last December.

His conduct “ranged from defrauding HMRC…to taking advantage of [an individual’s] disability …to personally benefit from salary enhancements to which he was not entitled”, according to a previous disciplinary tribunal. He bought a second home in Spain around the time of his offences, according to the council.

Cash had not been recovered in more than three-quarters of council-reported DSG fraud cases in 2020-21, although the process can be lengthy. A whistleblower first reported Bishop-Rowe in 2013.

A Buckinghamshire council spokesperson said it had “zero tolerance” of fraud, with seven of 10 reported cases “closed with appropriate sanctions and redress pursued”.

A Liverpool council spokesperson said notices were issued to support schools plugging deficits, including guidance and monitoring.

The DfE said supporting and monitoring maintained schools was local authorities’ responsibility.

Your thoughts