The government has been accused of wasting taxpayers’ money on its flagship free school project after an investigation found more than half of new places were in areas they were “not needed”.

The National Audit Office found that 57,500 of 113,500 new places in mainstream free schools opening between 2015 and 2021 will create ‘spare capacity’ in the immediate areas of some of the institutions.

Of those free schools which opened in 2015, 52 could have a “moderate or high impact” on the funding of any of 282 neighbouring schools, the report says.

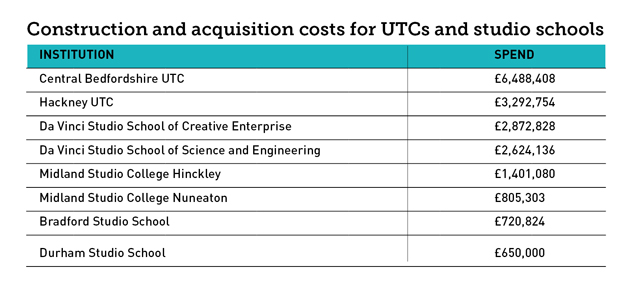

The watchdog is also warning that a scarcity of land for new free schools is pushing the capital spend on some institutions into the tens of millions of pounds – with four sites costing more than £30 million each.

Capital spending on schools reached £4.5 billion in 2015-16, but the NAO says the forecast deterioration in the condition of the school estate is a “significant risk to long-term value for money”, and has questioned the government’s approach to school places planning.

This is taxpayers’ money that could be used to fund much-needed improvements in thousands of existing school buildings

Meg Hillier, the Labour MP who chairs the parliamentary public accounts committee, accused the government of “choosing to open new free schools in areas which do not need them and are failing to fill places”.

“This is taxpayers’ money that could be used to fund much-needed improvements in thousands of existing school buildings,” she said.

The NAO report also calls into question the way school places are currently planned, with councils ultimately responsible for ensuring there are enough, but unable to open their own free schools or compel academy trusts to take on or expand existing schools.

The pressure on local authorities is expected to continue, the NAO says, with the government predicting it needs a further 231,000 primary places and 189,000 secondary places between 2016 and 2021.

This lack of alignment between the responsibilities and powers of councils has also been blamed for a dearth of information on how the condition of schools are changing over time.

The government “does not currently know with certainty how the condition of the estate is changing over time”, the NAO says.

The watchdog also describes the availability of suitable free school sites as the “biggest risk to delivering buildings for new free schools”, and warned the government often enters into “complex commercial agreements and pays large sums to secure sites in the right places”.

While the average cost of the 175 sites bought in recent years is £4.9 million, 24 of those cost more than £10 million each, and the cost of four of those sites exceeded £30 million. Of the 24 sites that cost more than £10 million, 22 were in London.

But Toby Young, the director of the New Schools Network, pointed out that report had found that free schools offered “better value for money than previous school building programmes”.

“They are the most cost effective way to create the 750,000 new school places we need between now and 2025. They are also more popular with parents and more likely to be rated ‘outstanding’ by Ofsted than any other type of school.”

The NAO has recommended that the government improve its understanding of the costs of capital projects run by councils and evaluate the quality of buildings provided through its main capital programmes.

Whitehall should also continue to improve its understanding of the condition of the school estate and consider how it can get “more value” out of the next property data survey while working more closely with local authorities to understand and meet need in local areas, the report said.

Applications for new free schools should also be assessed on whether the value gained from increasing choice and competition outweighs the “disadvantages of creating spare school places in a local area, including the impact on the financial sustainability of surrounding schools”.

A Department for Educations spokesperson said: “As the NAO acknowledges, we have made more school places available, and in the best schools.

“The free school programme is a vital part of this – more than three quarters of free schools have been approved in areas where there is already demand for new places and the vast majority are rated good or outstanding by Ofsted.”

I notice that Toby Young, like Nick Gibb on occasions, is using just Outstanding to compare FS against other schools.

Why?

Because if you use the standard – which is Good or Outstanding – the picture isn’t quite so good for him. 84% of FS are Good or Outstanding against 89% for all schools.Not significantly different but it really is tiresome to see him try and mislead people.

The number of free schools inspected isn’t large enough to reach a reliable conclusion about the effectiveness of free schools as a group. The NAO report recognises this. It says the DfE has tried to ‘assess whether creating free schools is having the intended effect of improving educational standards through competition but the sample size is currently too small to draw meaningful conclusions’.

Just found a DfE briefing paper dated December 2016. It says: ‘the number of free schools inspected so far is still quite small and so provide little firm evidence on performance so far.’

(Can’t provide a link but an internet search should find it. Its title is BRIEFING PAPER Number 7033, 2 December 2016, Free School Statistics’.

Toby Young says free schools are the ‘most cost effective’ way of supplying new school places. It is actually the only way since the Government decreed that all new schools should be free schools. But the NAO said there ‘can be an inherent tension’ in how far free schools can provide the programme’s aims ‘cost-effectively’.

The NAO said the DfE estimates that 57,500 of 113,500 new places in mainstream free schools opening between 2015 and 2021 will create spare capacity in some free schools’ immediate area.’ That’s nearly half of the estimated extra places resulting in surplus places locally. This can hardly be described as ‘cost-effective’.

Free schools were never going to work. Most are run by a bunch of amateurs with their own convenience in mind rather than that of the children. Teachers did not need full qualifications and the schools were sited mostly where there were already surplus places. The only sensible answer is to turn them over to local authorities when they could then become first choice schools for those who live nearest.