XP and XP East sit like tiny pods on a giant lot in a Doncaster retail park.

I’ve just been given a tour by a couple of year 8 students who’ve explained how they learn everything through half-termly “expeditions” (projects), don’t wear uniform “because they don’t want us to look all the same”, and find it perfectly normal that someone should apologise publicly in front of the entire school if they’ve done something wrong.

“You feel more safe,” says Alfie. “Bad things don’t go unnoticed.”

All 250 students participate in the weekly community meeting, where they can make “appreciations, apologies and stands”. Stands are issues you want the community to address, which could be anything from racism to single-use plastics.

Bad things don’t go unnoticed

Public appreciations are used in many schools – popularised by the US-based Knowledge is Power Programme, which is in some ways the ideological antithesis to the Expeditionary Learning (EL) model on which XP is based. Apologies and stands just evolved, explains trust CEO Gwyn ap Harri, a former edtech start-up founder who believes the tech process of iteration and continuous improvement can easily be applied to school design.

Alfie and Courtney are in the same “crew” – a team of 12 or 13 pupils that is basically a tutor group where they spend 45 minutes each morning. Crews form the bedrock of XP’s pastoral system. “If there’s something wrong, you can speak to your crew and your crew won’t tell anyone,” Courtney assures me.

Staff crew is a parallel concept. The initial start-up staff first met when they went on a camping trip together prior to their September 2014 opening.

Trust between pupils is built from day one of year 7, when they are packed off in their crews to employ the tried-and-tested techniques of map-reading and abseiling to build character and forge bonds. “One crew even slept on a boat!” Courtney tells me with delight.

Alfie enthuses about their first “expedition”, which was called What does our community owe to the miners? “We had lots of experts who came in, like former pit nurses who’d worked in the mine, and they’d tell us their own stories.”

“Expedition” in this context is similar to project-based learning. Each one takes half a term; is driven by a guiding question, such as “Am I responsible for my own thoughts and deeds?” or “When is it right to make a stand?”; and ends with a “product”, such as a book or an art exhibition, which must be “meaningful, beautiful work”. In this case it was a book, which is now sold in their local Waterstones.

Other expeditions have celebrated the NHS in Doncaster and explored the issues facing asylum seekers in their community. Staff plan the content collaboratively, making sure the entire academic curriculum is mapped to the expeditions. Anything that doesn’t fit in – quadratic equations or foreign languages, for example – is taught separately in traditional classes.

Both schools are strictly limited to 50 kids in a year, 25 in a class, and are run like tech start-ups, bootstrapping their way through the early years and being creative with the curriculum. “The model is affordable and fully costed. And it is replicable,” says Ap Harri.

Teachers teach cross-subject, making use of their interests as well as the subjects in which they are academically trained. Ap Harri teaches business and computing GCSE in the same classroom.

There are no departmental budgets, or even departments – but each expedition does have a budget to pay for materials, expert speakers and trips. The students I meet are preparing to go to see Romeo and Juliet in Blackpool as part of the Rebellion expedition.

But do they know at any given time whether they are learning English, history or geography? “It’s a bit mingled, to be honest,” Alfie tells me.

Ap Harri, a former computer science teacher, set up the XP free school (then a second one, XP East) with Andy Sprakes, a headteacher of 15 years, after being impressed by a visit to High Tech High in San Diego – a school that follows the EL approach.

“It was more than just an interesting way of delivering the curriculum; it was a whole ethos, a whole school. It was based on design principles. And, yes, it blew me away,” he recalls.

EL schools are small by design; learning is cross-curricular; and the aim is to inspire students to take ownership of their learning, prioritising self-discovery and service to the community.

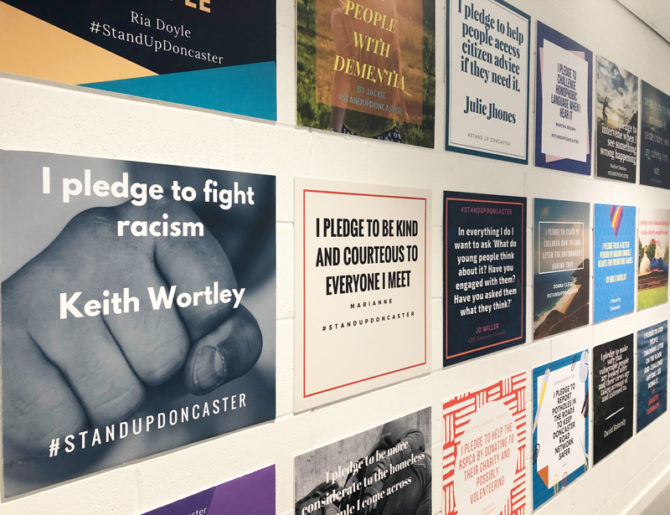

What seems to be running through the XP schools like words in a stick of rock is citizenship education, although nobody uses that phrase. The walls are covered with posters they’ve created with the local NHS trust, maps of refugee pathways peppered with words from the asylum seekers they’ve met, and quotes from community members who’ve made pledges that they’ve since followed up on.

Rather than create an educated elite who’ll head off to London once they’ve got their degree, Sprakes wants to create engaged community members. “We’re about, ‘Well, if you say Doncaster is a dump, why? And what are we doing about it? What are we doing to make the place where we were born a better place? And what’s your responsibility? Or is it somebody else’s problem?

“That’s why we connect with the community so much. That’s why we work with Age UK, environmental groups, the NHS, you name it. To create things that make Doncaster a better place.”

Careers are embedded in everything they do, but they don’t give two hoots about the Gatsby benchmarks. “That’s where the country’s going wrong!” says the head of XP East, Jamie Portman. “That’s the pressure of the accountability system that we’re under, which is ‘How can we show others that we’re doing careers?’

“We get experts in from the local authority, from business; we’ve had published authors in. Imagine being a kid where frequently people come in and they see, ‘Actually, you’re just like me. You might look posh, but you started out just like me, so maybe I can go to university too.’”

I choose one class to sit in on at random, a GCSE history class where the teacher is introducing a new expedition. As she coaxes a recalcitrant teen into focusing on the task at hand, I can’t help thinking how much less efficient the persuasion approach to behaviour is than, say, the SLANT approach, where students are trained to sit up straight and track the teacher with their eyes at all times.

Ap Harri says their approach is to create “deep and purposeful relationships” and he frames XP as the antidote to Outwood Grange and Delta – two local multi-academy trusts that have attracted media attention for their strict behaviour policies and high fixed-term exclusion rates. His claims that they are permanently excluding high levels of pupils with special needs aren’t backed up by the data, however.

XP has, he admits, permanently excluded one child since they opened. “We shouldn’t have had to but we didn’t have the support from the local authority. That kid’s now accessing the mental health pupil referral unit. We haven’t since,” he says.

“Because you don’t have to!” says Sprakes, who’s worked in challenging schools in ex-mining communities. “You’ve got to try to find an environment or a situation where that kid’s needs will be met.”

This doesn’t mean they go soft on behaviour, insists Ap Harri. “We’re really hard on the kids. You ask the kids about the difficult conversations they have to have when they’ve got to put things right.

“It would be easier for me to say, ‘Right, here’s a set of rules. If you transgress any of those then you’re out and you become somebody else’s problem.’ The difficult job is when you’ve done something wrong, how do you put that right now? And then how do you show that sincerity?”

XP were able to start from scratch and sell their vision to new parents. Could they have held to their values if they’d inherited an existing school – one with a history of low aspirations and under-performance?

Why not just bulldoze it and build some more of these?

“With primary schools, yes,” says Ap Harri. “We’ve got one in our trust. We’re hopefully going to be joined by a few more this year. One is a struggling primary school that we’re turning around.”

Ap Harri seems less enthused at the prospect of turning around a secondary. “Why not just bulldoze it and build some more of these? Because it works.”

The school’s first Ofsted report, in 2017, was glowing, with outstanding in every category. Whether they will also produce good grades is yet to be seen – their first cohort of year 11s will sit their exams this summer.

Ap Harri knows the survival of his school depends on getting good results, but doesn’t believe it should be his sole focus. “We see results as a consequence of what we do – rather than the reason, the purpose.

“If you come to school every day, work hard, be kind, produce beautiful work and become a better person, you’ll achieve academically – that’s our narrative for success.”

Your thoughts