The government will use the UK’s position in the international PISA tests taken by 15-year-olds to judge the success of its extensive exam reforms, the Department for Education (DfE) has confirmed.

The department’s support for PISA was unveiled in supplementary evidence sent to the education select committee after education secretary Nicky Morgan was pushed to give details of how the changes would be measured.

Questioned in a committee meeting last month, Ms Morgan (pictured) was unable to pinpoint how government changes to GCSEs and A-levels would be measured but said: “I am happy to write to you with some thoughts about how we can measure things.”

The DfE last week responded with clearer details of its plans in correspondence to the committee, later published on the committee’s website.

On measures for effectiveness the department wrote: “We will be listening carefully to the views of employers and universities to assess how successful the reforms have been in preparing students to succeed in life in modern Britain.

“We will also measure the increased performance of the school system as a whole by reference to international tables of student attainment, such as PISA.”

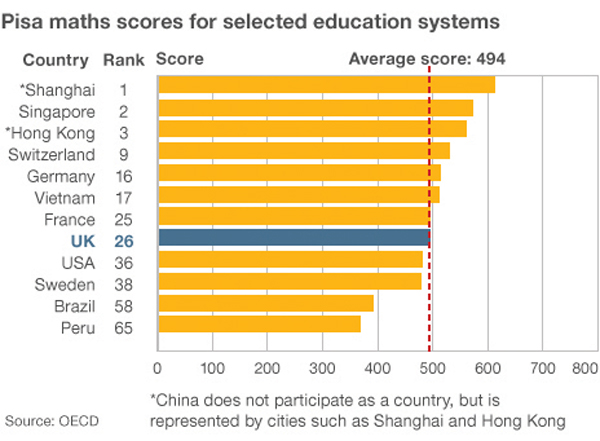

In the last OECD PISA league tables, published in 2013 and based on tests taken by 15-year-olds in 2012, the UK was ranked 26th in the world, with Shanghai topping the list of 65 countries and regions. The OECD carries out the survey every three years, with one scheduled for this year.

However, the impact of the exam reforms will not be able to be measured until the 2018 survey.

Ms Morgan agreed to write to the committee after the chairman, Conservative MP Graham Stuart, asked how the government was planning to make sure its reforms had “delivered”.

Ms Morgan said that a range of factors such as the feedback from universities and employers would be considered, but that she was “not going to set out” how the government would measure and review success.

Asked about PISA, Ms Morgan agreed that it was one way to measure performance, but did not say that it would be used as a target. Instead, she offered to write to the committee.

The far-reaching reforms, introduced by her predecessor Michael Gove, include the decoupling of AS-levels from A-levels this September and, at GCSE, schools will no longer be measured based on the number of pupils achieving five A*-Cs, including English and maths, but rather on the Progress 8 measure.

Pisa: or International League Scores for 15 year olds,

The areas of testing are: Mathematics, Science and Reading.

Shanghai Singapore and Hong Kong have the highest scores across all three areas in 2009. The 2015 results out today show little change at the top.

Mathematics Science Reading

Germany 16 12 19

Ireland 20 14 7

United Kingdom 26 20 23

United States 36 28 24

The above table gives the positions of each of the 3 countries in a list of 65 countries arranged in a hierarchy of academic ability. Two things stand out. One is the amazing consistency of the top 3 countries over recent years. The second is the radical differences between the 4 countries in the table, and within the 4 countries.

Firstly, the three winners from Asia have been celebrated for their success. High teacher pay, and high levels of training are praised. Also, problem solving is praised over rote learning.

Secondly, the differences within Germany fit the national stereotype for Maths and Science; but not Reading. The scores for Ireland put it only 5 places below Germany for maths. For Science the score is even higher, and for reading it has the same score as Canada and Finland. The first 5 scores for reading are all from Asia. The United Kingdom scores are closer together for each of the 3 subjects than any of the other 3 countries. The United States scores are significantly worse than the other 3 countries for all subjects

.

This raises the following questions:

1 Why is Germany so poor at reading? Pisa claims that reading is not about word recognition or spelling; but is about reconstructing, extending and reflecting on the meaning.

2 Why is Ireland so good at reading? Does the high score imply that Irish schools are more focused on the meaning of words, and literature?

3 Why has the United Kingdom roughly similar scores across the 3 subjects? Does this imply a government’s view that each of the 3 subjects are equally important?

4 Why is the United States in the bottom half of the 65 countries of the world? The scores in reading and science are much better than in mathematics. Is science a smaller part of the overall curriculum in the schools?

Critics have pointed to the multiple choice part of the assessment. How appropriate is this for reading, or science? Also not all parts of the full assessment are done by all of the 5,000 plus students in each country. Has Ireland benefited from the “fuller” answers allowed for some of the reading? It is not clear whether practical experiments are present in the science assessments at all, or even for some students , but not others. What is claimed to be important in science is identifying new questions from existing research.

Finally, the concerns of British employers for maths and English from 16 year old students can be quite strident. But Britain is well into the top half of the 65 countries on this evidence. So illiterate and innumerate students are not the main problem.

27 May 2015.