A government review concluded that extending the school day would involve “significant delivery considerations” including teaching capacity, new legislation and accountability measures to ensure quality.

The Department for Education has finally published a five-page summary of its review of time spent in school, which ministers had promised to publish before last week’s spending review.

Last week’s funding settlement for schools included no money for a longer school day for most pupils, instead allocating £800 million for more funded provision for 16 to 19-year-olds, and a £1 billion extension of the recovery premium.

The Department for Education said at the time that it had decided the measures prioritised would be more effective for catch-up, but did not commit to publishing the findings of the review.

However, a short document was released tonight setting out the evidence ministers considered when making their decisions.

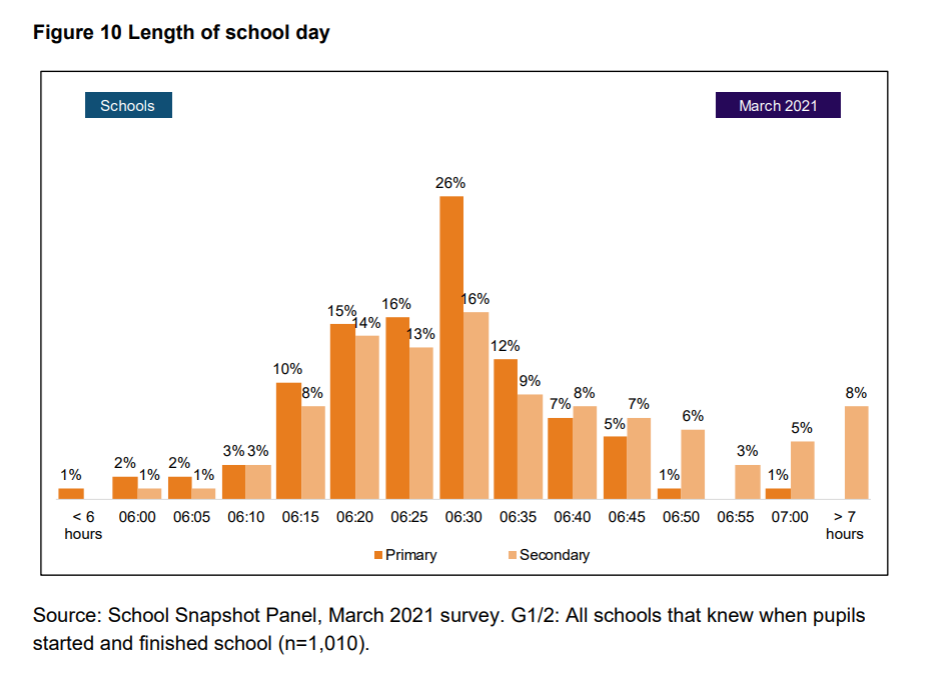

It reiterates the findings from a March school snapshot survey, published last week, which found that pre-pandemic the average school day was 6.5 hours. However, this was only based on a survey of 1,010 school staff.

It also stated that “initial analysis” suggested little or no difference in length of school day based on school characteristics, such as free school meals eligibility, urban vs rural settings and maintained schools vs academies. However, there was no reference to where this came from.

Among academic studies and international comparisons, the DfE quoted a Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) which found the average number of instructional hours per year in English primary schools is above the median for pupils in year 5 compared to “participating countries”.

At secondary schools it is “broadly median” for year 9 pupils.

Concluding the review, DfE said “any universal change” to the length of the school day would involve “significant delivery considerations, particularly how to realise the additional teaching capacity required in order to facilitate delivery within existing legislative, contractual and workforce supply constraints”.

The challenge of ensuring that any additional time is “not only delivered, but also used well, would require legislation and accountability measures sufficient to ensure quality”, the review added.

As teaching hours in 16 to 19 are lower than pre-16, an increase is “much more feasible” particularly “as the legislative and accountability frameworks to do so are already in place”, the DfE added.

“Generally too, the structure of teaching and learning time in 16 to 19 education (for example, free periods) provides opportunities to more fully utilise a ‘standard’ day or week.

“Given international practice and engagement with the sector we have a high degree of confidence that there is capacity to deliver quality additional time in 16 to 19 education.”

James Bowen, director of policy at school leaders’ union NAHT, said it is now “important” the sector “moves on” from the “unhelpful debate and focus on things that really do make a difference”.

Education secretary Nadhim Zahawi was pushed this week by education select committee chair Robert Halfon on whether a pilot could be launched, as suggested by former catch-up commissioner Sir Kevan Collins.

But Zahawi wouldn’t commit, and instead repeated called for schools operating below the 6.5 hour average to move towards that, but without any extra funding.

He said there are “great examples already” of MATs that have chosen to have a longer day, adding: “I want to look at what they’ve done and encourage a spread of good practice.”

A recent study of around 100 schools by charity Impetus, one of five involved in the set up of the National Tutoring Programme, found that there is “not a cut and dried case of extending the school day to improve outcomes”.

While there was a “strong relationship” at GCSEs between longer school days and results, it “all but disappeared” when other schools were added into the sample.

But it added that all the findings “must be taken cautiously” because “they appear to conceal what is really happening within the schools and the impact this is having on their pupils”.

The Education Endowment Foundation found that extending the school day could held children catch up by three months – but “are expensive and may not be cost-effective for schools to implement”.

6.5 hours per day and yet our youngest children in non-statutory spend 7 hours per day.

A 3 year old time compared to a 16 year old is a staggering admission that the younger you are the more hours you must spend in school.

Then you reflect on the 2 year old who enters nursery at 7.30am and then has a 10 hour day.

I would prefer to not count the hours but actually consider how effective is a typical day for every key stage. If children were not rushed through dinner times they could develop conversation. If children had reasonable time they could enjoy an art class or a music class. If children had lots of short breaks they would concentrate better. If children were allowed to relax they might foster the relationships they need to thrive with key workers during a school day. My list is endless.

As for school staff they need greater non contact time to support well-being but also develop with quality CPD.

While few admit, the real reason none of this working is that school staff provide hours of unpaid time and if the status quo is relying on goodwill of unpaid time asking for more hours is unworkable.