Schools Week can today reveal how the toxic legacy of costly PFI contracts threatens to derail the government’s promised “academies revolution”.

Our three-month investigation has uncovered how cash-strapped, failing schools are seeing potentially transformative takeovers hit the buffers as academy chains baulk at taking on lengthy contracts to repay the private firms who built the schools.

Senior reporter John Dickens investigates…

In 2007, then prime minister Gordon Brown stood on the spotless corridors of the £24 million Bristol Brunel Academy and proudly declared that under his government “no child will be left behind”.

In a YouTube video – still viewable on the official 10 Downing Street channel (pictured) – Mr Brown was opening the first school to be built by the £50 billion Building Schools for the Future project.

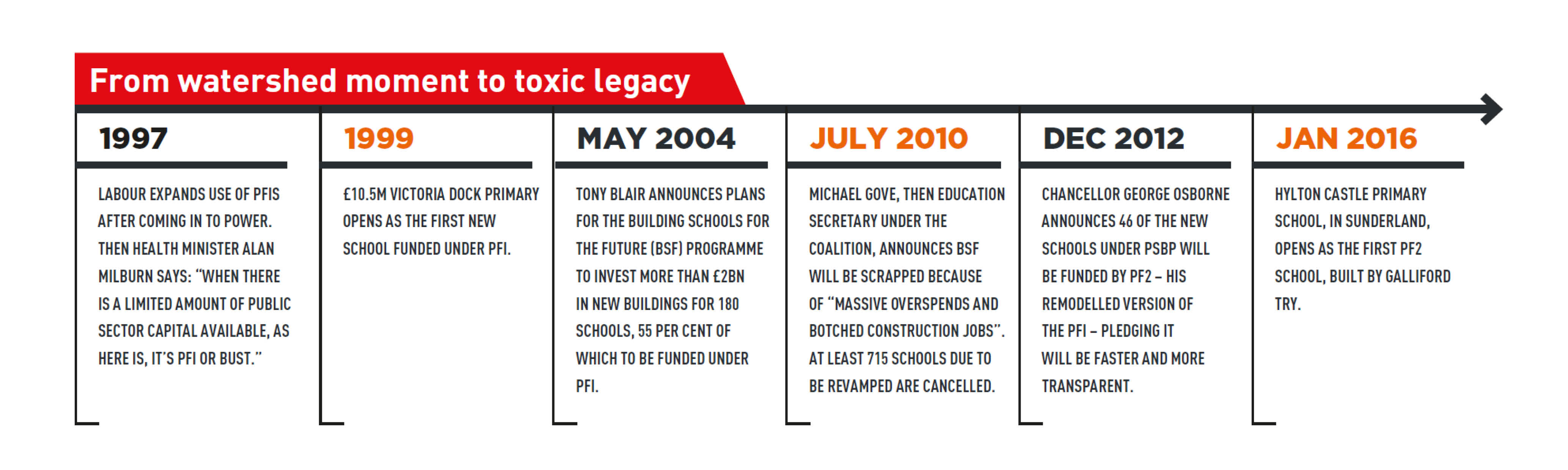

It was part of Tony Blair’s pledge to rebuild or refurbish every secondary in England over 15 years after New Labour swept into power in 1997.

But the unprecedented investment relied on schools being paid via private finance initiatives (PFI) in which private companies paid to build the schools. The investment is then recouped – with interest – by leasing buildings back to the government on 25-year or longer contracts.

It was buy now, pay later. Debts were kept off the government’s balance sheet and to be picked up by future taxpayers. The scheme took off and the Department for Education (DfE) took on 168 PFI projects of varying size – the most of any government department.

But less than 10 years on from the opening of Bristol Brunel, the promise to transform schools has instead soured into a toxic legacy.

It now threatens to stop the Conservative government’s vision of an “academies revolution” – in which failing schools get new super-bosses – as experienced academy trusts turn their back on struggling schools because of the hefty PFI costs that come with them.

The findings of a three-month investigation by Schools Week lay bare the consequences.

What’s going wrong?

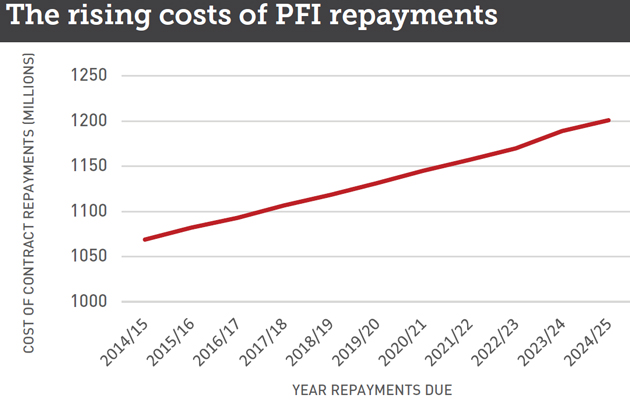

When local authorities originally signed off the PFI deals, they knew how much had to be paid back. They knew their contract repayments would rise slightly each year, linked to the rate of inflation or the Retail Prices Index.

But with the change of government in 2010 came a new era of austerity.

Now, schools’ budgets are squeezed. Together with increased pension and national insurance costs, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has predicted per-pupil funding could fall by 8 per cent in real terms by 2020.

Schools are slashing costs however they can, with some making redundancies. But they cannot easily cut the costs of PFI.

The pressure is pushing some schools deep into the red. Schools Week has previously revealed that repayments at Birches Head Academy, in Stoke-on-Trent, have soared by more than £125,000 in four years, up to £380,000 a year.

The school was – until last month – in special measures. But talks for a takeover by Ofsted-rated outstanding St Joseph’s College have been delayed because governors are reluctant to take on a financial liability.

St Joseph’s College headteacher Roisin Maguire said: “Without PFI, the school would have been converted by now. But it is being held back.”

Yet Nicky Morgan said when launching her landmark education bill to speed up intervention in failing schools: “We think a day spent in a failing school is a day too long when education is at stake.”

The PFI legacy is thwarting that commitment.

Delays hinder transformation

Ofsted has attacked “repeated delays” over the potential transformation of one PFI school: Sandon Business and Enterprise College, also in Stoke-on-Trent, which is in special measures.

Ormiston Academies Trust, which has a track record of turning around struggling schools, has been named as the preferred sponsor but the takeover has hit the buffers.

In an Ofsted report earlier this month, inspector Alun Williams said the “ongoing saga” was an unhelpful distraction to

school leaders.

“It is to their credit that it does not appear to have slowed down the school’s progress, but it has meant them expending valuable time and energy on issues that are not central to seeing Sandon improve.”

Ormiston has written to schools minister Lord Nash about the issue and said this week it is doing all it can to complete the conversion without further delay.

But other academy chains are reluctant to take on PFI schools. The country’s largest chain, Academies Enterprise Trust, has already spoken about its issues with PFI, while Schools Week has been told by leaders of several other chains they are concerned.

A spokesperson for the DfE told Schools Week that where necessary it was happy to work with partners “to overcome any issues facing schools with PFI contracts wishing to become academies, to enable them to enjoy the benefits this status brings”.

But Jonathan Simons, the head of education at thinktank Policy Exchange, said: “As a multi-academy trust there is no way in good fiduciary duty or conscience that you could take on a school with a big PFI debt that you didn’t get sufficient funding for. Academy chains say the money they get for PFI does not cover the costs.”

Unable to become a multi-academy trust

And it’s not just struggling schools experiencing problems. Three schools in Newham – Lister Community School, Rokeby School, Sarah Bonnell School – want to form a multi-academy trust.

However, two of the schools have PFI contracts, both said to be costing more than £1 million a year. The council has asked the schools to raise their contributions by a combined £400,000 a year, but the schools have said they simply cannot afford to do that.

Talks are reportedly in deadlock more than a year after the schools announced they would convert. A spokesperson for the schools said they need to convert to go from “good to great” and called the delay “frustrating”.

Whole regions unable to resolve financial issues

Schools Week has uncovered PFI problems in regions across the country.

Schools in Barnsley have raised concerns over the financial challenges facing those with PFI contracts. Schools Week understands academy chains have walked away from takeovers because of the large repayments associated with some schools.

Barnsley council said schools pay £3 million towards their PFI funding gap – where budget cuts and rising PFI costs have created a gap between the money coming in to pay the contract and the amount actually going out. It acknowledged this was significant, but said the contributions had secured state-of-the-art facilities that had enhanced standards for pupils.

A spokesperson said some sponsors may have reservations taking over the schools, but said it has not prevented nearly half of the PFI schools from already converting. The council said it recognised the strain of the schools’ PFI contributions and is reviewing the contract to make savings.

A spokesperson for the Barnsley Governors Association added: “In time, the decision to build them will be seen as a turning point for Barnsley’s students.”

Cutting costs to plug PFI blackholes

Some local councils – who manage contracts on behalf of schools – are trying to plug the funding gap by taking cash from their dedicated school grants, meaning less cash is available to hand out to schools.

Others councils are exploring other means of cutting costs. Wirral Council axed swimming lessons for pupils and special educational needs budgets to meet its

£2.3 million PFI shortfall last year.

Frank Field, Labour MP for Birkenhead, said: “The council should make it clear to the PFI contractors that it isn’t paying them another penny … The alternative is that some of Wirral’s most disadvantaged children will suffer a worse education.”

Conversion costs mounting up

Legal costs of converting are also rising. Sir John Colfox, an Ofsted-good rated secondary in Dorset, had to wait more than two years – from January 2013 to April last year – to convert into an academy. It was one of the first schools in the country to open under PFI funding in 1999 and now pays more than £1 million every year in repayments.

Dorset County Council said it spent more than £35,000 on legal fees on the conversion, with the school stumping up even more. A legal expert told Schools Week the average cost of conversion is between £6,000 to £10,000.

Who is responsible?

That very much depends upon who you ask. Media reports often paint private firms as the baddies. While some firms are making million-pound profits, the repayments were agreed with local authorities. The yearly inflation rises were also signed by both parties.

Private firms say they delivered projects on time and at cost – an improvement on the government’s record.

Some schools are happy with their PFI. Steve Taylor, chief executive of the Cabot Learning Federation, which now runs Bristol Brunel, told Schools Week it has a new, state-of-the-art school which provides a “fantastic learning environment” for pupils – although he says the longer term benefit is more difficult to anticipate.

Speaking to Schools Week earlier this month, Lord Storey (pictured right) said he was proud of his education achievements while leading Liverpool City Council, which included PFI deals. “PFI is very controversial and very expensive, but looking back on it, it was the only option in town.”

Local authorities ultimately hold the key to ensuring a contract runs smoothly and have faced criticism for poor management. But councils relied on experienced staff to run the contracts. Now, in many cases, those well-paid experts have been let go to meet funding cuts.

PFI was concocted by the government and many would argue the buck stops with it. The deals have come under heavy scrutiny by various government inquiries in 2011, leading to spending watchdog, the National Audit Office, concluding PFI is not best value for money.

The government has since scaled down its PFI plans. With cutting the deficit still top of the political agenda, a revamped version of PFI – called PF2 – has now risen from its ashes. While the government claims the scheme will address many of the problems caused by PFI, experts warn there is likely to be trouble ahead.

In the 2007 video, Mr Brown breaks into a smile while speaking to pupils on his tour around the Bristol Brunel Academy.

Pupils are later told by then chancellor Ed Balls that they were witnessing a “watershed” moment that “sets the standard for future generations”.

But now something needs to be done to ensure those future generations – today’s pupils – are not left paying the cost of picking up the PFI tab.

OTHER STORIES FROM OUR PFI INVESTIGATION:

Revealed: The true scale of school PFI debts

The future: Fair Funding Formula could be toxic for PFI schools

The future: Will schools get a better deal under PF2

The PFI firms: Multi-million pound profits from flipping contracts

The PFI firms: The low-key investment firm that owns 260 UK schools

It would probably make sense for the government to buy these contracts back and bring them into public ownership. The government can get the finance for these at negligible interest rates. Refinancing would likely save a lot of money. See page 12: http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06007/SN06007.pdf

Although, there seems mainstream political preference for private finance because it appears that government is not spending.

Perhaps an article Schoolsweek by economist Ann Petifor might be informative.

https://mobile.twitter.com/annpettifor/status/517661910104559616

Well it is an ill wind is it not, that blows to halt academisation. And it cannot not be a factor that “struggling” schools with their inevitably less money for enough TAs etc would find life difficult. It must be unbearable. As a peripatetic teacher I frequently visit schools built with PFI and, while they are expensive to repay, they were most definitely built on the cheap. Science colleagues have talked to me with dismay about inappropriate storage for equipment. A TA from X said, yes we had extensive conversations with the builders and then they did as they pleased. Music rooms are okay as long as you buy nice gleaming electronic keyboards from the nice gleaming keyboard selling factories. Heavens help those of us who recognise the benefits of a steel pan, or a few djembes! Gamelan anyone? [Ours from my Special Needs Music charity is in permanent storage. It should be in permanent use.]

And I could write a book on the “flexible space”. This is the hall, dining hall, sports hall, dance hall, drama hall, music room, which can only be used for the one when it is not used for the other. And I love sliding on disintegrating cauliflower as I set up some steel pans.

PFI was a scam from the start, bleeding dry schools [and hospitals and I think theft should be punished by law, not encouraged. The silver lining that it stops even a few greedy little businesspeople from getting their paws on yet another public institution can however only raise a small smile.