Prime minister Rishi Sunak has outlined vague plans for all pupils to study maths until the age of 18. But can he honour an ambitious promise that Labour calls “a reheated pledge”?

Schools Week takes a closer look…

What’s being proposed?

Rishi Sunak’s “ambition” is for all school pupils to study “some form of maths” until the age of 18.

He “does not envisage” making maths A-level compulsory, instead “exploring existing routes” – such as core maths and T-levels – or “more innovative” choices.

This would make numeracy a “central objective of our education system”, giving people the ability to do their jobs better and “get paid more”, he said.

But that was it for details.

The prime minister also only committed to starting work to introduce the policy in this parliament, meaning any reform would not be achieved until 2025 at the earliest.

With the Conservatives tanking in the polls, it will likely be down to a new government to decide whether to implement the policy.

How many pupils will it affect?

The government said only about half of 16 to 19-year-olds studied any maths, warning the problem was “particularly acute for disadvantaged pupils”.

It’s not clear how this has been worked out, and whether it includes other A-level subjects in which maths is a key component.

Ofqual data shows that about 580,000 16-year-olds in England took GCSE maths last year, with just shy of 90,000 entries this summer to A-level maths – the most popular A-level subject. Another 15,000 took further maths and 12,000 sat core maths.

Meanwhile, roughly 145,000 pupils who don’t get a grade 4 or above at GCSE continue to study the subject post-16 until they pass.

How could the policy work?

The vagueness of the announcement gives the government huge flexibility on what it could look like in practice.

Jonathan Simons, the head of education practice at Public First, said: “At one end, this could mean an enrichment club.

“It could be a qualification like general studies where you have to sit an exam but no one counts it, or it could mean having to pass a qualification that counts in league tables.” He suggested 2030 as a feasible date for such reforms.

Sir Adrian Smith, the author of a government-commissioned study in 2017 into the feasibility of maths to 18, said it should be part of a “wider reform” to post-16. He wants a baccalaureate style system that will give a broader education than A-levels.

During his first leadership bid, Sunak pledged to introduce a “British baccalaureate” that would involve compulsory maths and English to age 18.

In a statement this week, Smith said such “radical” changes would not be easy and would take time. “We need to get started now and build a cross-party approach with support from teachers, students, parents and employers.”

Labour did not respond to a request for comment on whether it supported baccalaureate reforms.

What are the barriers to compulsory maths?

We’ve been here before. In 2011, a report for the Conservative party by Carol Vorderman, the mathematician and TV presenter, recommended all pupils should study maths to 18.

Michael Gove, the education secretary, said at the time he would like the “vast majority” of pupils to do so within a decade. But it never came to pass.

Smith’s 2017 report concluded there was a “strong case for higher uptake of 16-18 mathematics” and that the government should “set an ambition for 16-18 mathematics to become universal in 10 years”.

But the lack of maths teachers is a huge problem. The Smith report admitted teacher supply challenges were significant and that it was clear when there would be enough specialist staff for universal maths to become “a realistic proposition”.

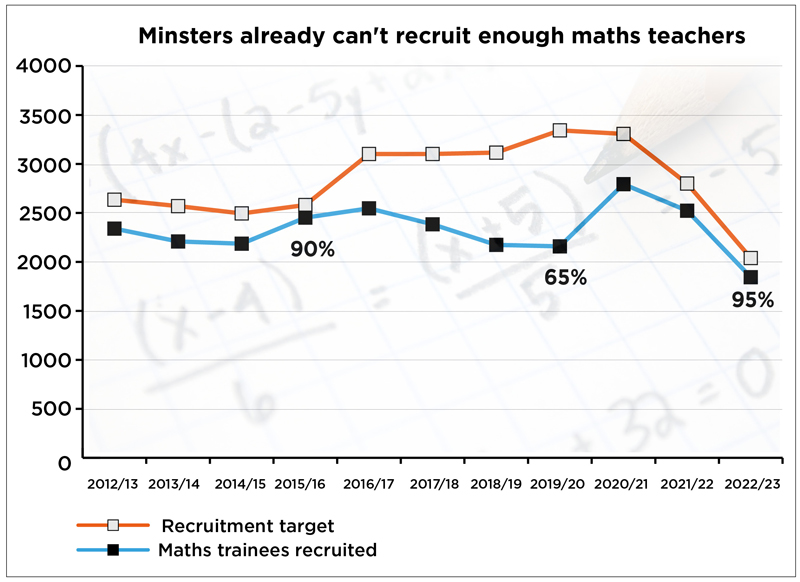

The government has missed its recruitment target for maths teachers every year since at least 2012. A National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) study last year found nearly half of secondary schools already used non-specialists for some maths lessons.

In 2020, 8.3 per cent of maths specialists left teaching, the second highest attrition rate of any subject.

Bridget Phillipson, the shadow education secretary, said the prime minister needed to show his working. “He cannot deliver this reheated, empty pledge without more maths teachers.”

Jack Worth, the NFER’s school workforce lead, said it was not clear how the government intended to meet current targets, “let alone how the additional teachers required would be attracted into the profession and retained”.

Schools Week understands the issue is being viewed by policymakers as part of a bigger workforce problem that will get wider focus.

Do we already have a suitable qualification?

In 2014, Nick Gibb, the schools minister, announced new core qualifications for pupils with at least a C in GCSE maths to continue to study the subject without taking a full A-level.

It focuses on using maths skills in business and personal life – for instance understanding investments and mortgage loans.

Gibb said the ambition was that by 2020, the “great majority of young people will continue to study maths to age 18”. While take-up has risen quickly, just 12,000 pupils sat core maths last year – way below Gibb’s promise.

Core maths is available in just 30 per cent of schools and colleges that offer A-level maths, according to Mathematics Education Innovation, leaving “large numbers of young people” who cannot access it.

Tom Richmond, a policy expert and ex-DfE adviser, said lower levels of per-pupil funding in post-16 meant there was no money left “so schools and colleges often can’t afford the ‘nice to have’ stuff. So what was government expecting to happen?”

Another sticking point is that an A in core maths attracts just 20 UCAS points when applying for university, less than half of an A-level value.

In January last year, the Royal Society and British Academy issued a rallying call to make sure “the potential of core maths is realised”. They demanded additional funding for schools to provide the qualification, with universities encouraged to incentivise take-up.

But Catherine Sezen, the education director at the Association of Colleges, said a “thorough” review of maths from age 14 was needed, given the “unhelpful cliff-edge nature” for those “forced to resit their exams”.

Can tech provide a solution?

The government funds the advanced maths support programme to help schools and colleges expand their post-16 maths curriculum, with more than 3,000 schools taking part since its launch in 2018.

The Smith review found there was potential for massive open online courses (MOOCs), but cited an earlier government study that said such courses had “high rates of failure” and were “likely to remain viable options only for motivated pupils”.

Simons said a certified MOOC could be an option. He said it was “entirely possible” that the Oak National Academy quango could commission such courses that students would have to complete before 18.

Exam boards back technology, too. Sharon Hague, the managing director of Pearson’s school qualification division, said that utilising technology to deliver new curriculum content, digital resource innovation, and developing flexible assessment approaches, could support the proposed policy.

But for others, it misses the point. Professor Becky Francis, the chief executive of the Education Endowment Foundation, said a better focus would be supporting “more young people – particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds to achieve a good grounding in maths by the age of 16”.

Has anyone taken into account pupils with discalculia?

Like dislexia, it really does exist. I know as I have it. I cannot do maths for maths sake, though I later discovered that I could if it was applied, as in chemistry. Numbers to me are meaningless otherwise.

To this day I am not sure that educators are helping pupils with discalculia, or even acknowledge it’s existence.

.