Female Ofsted inspectors are more likely to hand out harsher grades for primary schools than their male counterparts, new research suggests.

A study by the University of Southampton and UCL also shows higher grades handed out by freelance inspectors – mostly people who also work in schools – than those who work for the watchdog full-time.

It is the first independent research into how school inspection outcomes are linked to characteristics of lead inspectors, authors said.

Academics looked at overall Ofsted grades awarded by 1,376 inspectors across 35,751 inspections between 2012 and 2019.

Dr Sam Sims of the UCL Centre for Education Policy, who co-authored the report, said the analysis showed “characteristics of the lead inspector can influence the Ofsted grade awarded to the school”.

Inspections since the education inspection framework’s (EIF) introduction in September 2019 – which were disrupted by Covid – were not analysed due to a lack of data.

Ruth Maisey, programme head for education at the Nuffield Foundation, which supported the study, said the framework was “arguably more subjective” than its predecessor.

“As a result, we might expect differences between inspectors to be greater. We would like to see Ofsted reflecting on these findings and seeking ways to improve the consistency of inspections.”

But Ofsted has emphasised that because inspections are “human judgements and not a tick-box exercise so there will always be a small unavoidable element of variability between inspectors.”

It also added that it was “pleased” to see the research “shows broadly that our inspectors reach consistent conclusions.”

Below is a roundup of the research’s main findings.

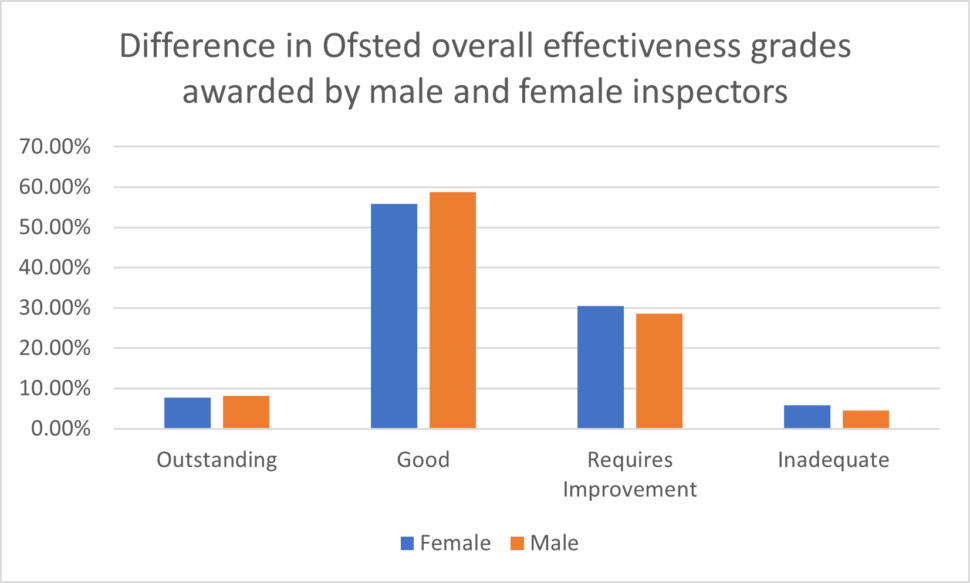

1. Male Ofsted inspectors more lenient at primary …

Analysis of the distribution of overall grades given to primary schools by male and female inspectors suggests the former tend to be more lenient.

Most strikingly, 36.4 per cent of primary inspections led by a woman resulted in ‘requires improvement’ (RI) or ‘inadequate’ ratings, compared with 33.1 per cent of those led by men.

Researchers say that while the three percentage point difference is “modest”, the large sample size means it is “statistically significant”.

This particular analysis looked at 22,754 inspections – 11,056 of which were led by women and 11,698 of which were led by men.

The distribution of different types of schools inspected also looked similar for both male and female inspectors.

For example, 8 per cent of primary school inspections led by both genders were previously ‘outstanding’, while 4 per cent were previously ‘inadequate’.

Meanwhile, 22 per cent of primary schools inspected by females were in the highest quintile in terms of free school meals, versus 20 per cent of those inspected by males.

2. … AND in short inspections …

Schools given short inspections can retain their grade, receive a new judgment or be given a full inspection within the next year due to either progress or concerns.

More than half of all school inspections between September 2016 and August 2019 were short inspections.

During this type of inspection, men were found to be more lenient than women.

Of those led by men, 9.6 per cent led to a “negative outcome” – either an immediate downgrade in the school’s overall effectiveness or a recommendation that a full inspection be conducted due to concerns.

This compares with 12.1 per cent of those led by women.

“In other words, short primary inspections are about 25 per cent more likely to result in a negative outcome if it is led by a female inspector,” the paper stated.

The analysis looked at primary school inspections only, due to having a larger sample size. Data was also controlled for differences in the background of schools.

3. … But no clear cut differences among secondaries

There was less evidence of a gender difference in secondary school inspection outcomes.

Of those inspections led by women, 10.9 per cent were rated ‘outstanding’, compared with 10.1 per cent of those led by males.

The difference between the percentage of grades given out by both genders was also less than one per cent for ‘good’ and RI.

The analysis found that 10.5 per cent of inspections led by men resulted in ‘inadequate’ ratings, versus 9.1 per cent of those led by women.

But researchers said the “much smaller sample size means we have much less confidence in this difference being a genuine result”.

Researchers looked at 2,188 inspections led by women and 2,813 led by men for the analysis.

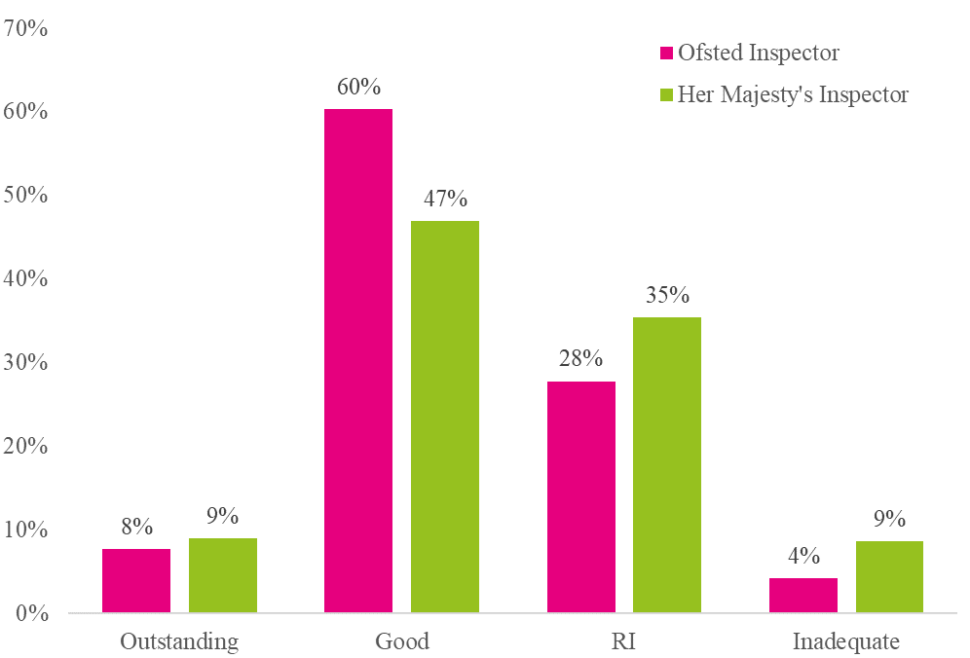

4. HMIs might be harsher than part-time inspectors …

The study also looked at the distribution of grades given out by Her Majesty’s Inspectors (HMIs) and Ofsted inspectors (OIs).

HMIs are civil servants who work full-time for Ofsted, while OIs work for the watchdog on a freelance basis and often hold a job elsewhere in the sector, such as as a headteacher.

The study found HMIs were less likely than OIs to judge a primary school to be ‘good’ (47 per cent compared with 60 per cent).

They were also more likely to award an RI or ‘inadequate’ grade.

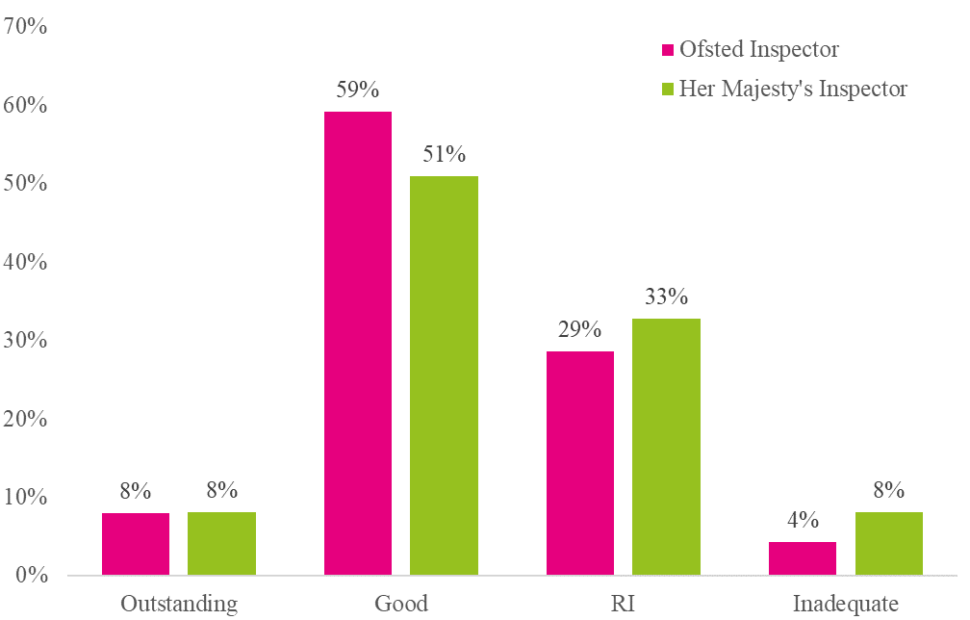

Researchers said the “magnitude of difference” was smaller at secondary level, “though a similar pattern emerges”.

Meanwhile, outcomes in short inspections led by OIs also tended to be more lenient than in those led by HMIs.

5. … But HMIs more likely to inspect worse schools

But there is also evidence that HMIs disproportionately lead inspections of schools with lower levels of performance in national exams and that were judged to be ‘inadequate’ in their last inspection.

Of the schools inspected by HMIs, 31 per cent were in the lowest quintile in terms of key stage 2 maths achievement. This is compared to 22 per cent of the school inspected by OIs.

Meanwhile, 14 per cent of schools inspected by HMIs were previously rated ‘inadequate’, compared with 2 per cent of those inspected by OIs.

Schools previously rated ‘outstanding’ made up 13 per cent of those inspected by HMIs and 7 per cent of those inspected by OIs.

Researchers said, however, that even after “controlling” for differences in the types of inspections both HMIs and OIs conduct, there is still a gap.

“Ofsted may select HMIs and OIs to lead inspections in ways that we cannot observe – and thus are unable to control for in our analysis,” the paper stated.

“At the same time, we believe it unlikely that further differences in HMI and OI deployment would explain all the remaining gap.”

6. Transparency call over inspector deployments

Based on their findings, the report made two recommendations to the inspectorate.

They urged Ofsted to publish details about how inspectors are deployed to different inspections.

“This is important because, if different inspectors award slightly different grades, we need to know which types of schools are likely to be disadvantaged by this,” they said.

A call was also made for Ofsted to make an inspection-inspector linked dataset accessible to researchers in order to facilitate further analysis of inspections.

As public data does not include such information, researchers used coding to predict the gender of inspectors, based on their first names.

In instances where an “ambiguous” result was produced, they manually inputted genders.

While they admitted the method was “imperfect”, the co-authors said it would not influence the outcomes of their analysis given the sample size.

Your thoughts