Love him or loathe him, Nick Gibb was made for the job of schools minister, says Jonathan Simons

For students of history, the Long Parliament sat from 1640 to 1660. It marked the period during which the legislature wrestled with the executive and the monarch over who governed Britain. And, although lesser known, it was also the first time Nick Gibb was appointed minister for schools.

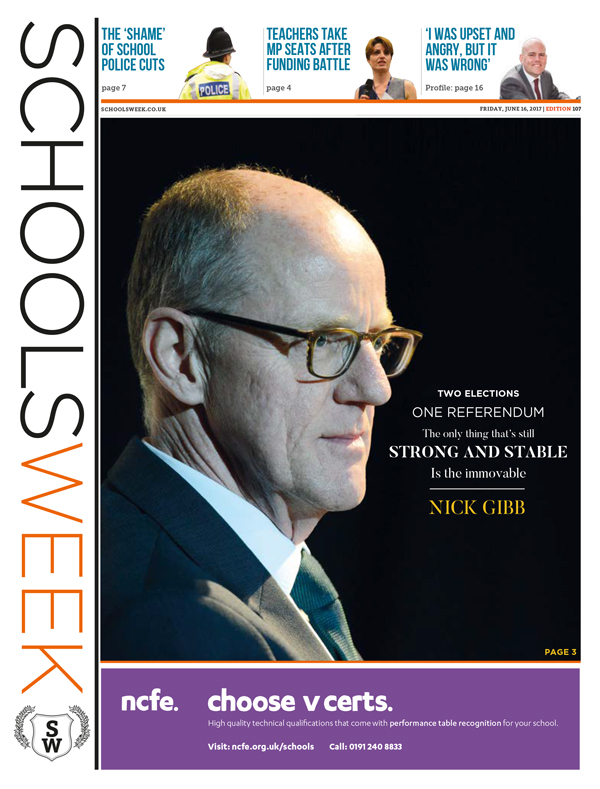

In retrospect, we should have known. Each of the 28 previous reshuffles while he’s been in office have been marked by frantic discussions of “what will happen to Nick Gibb”? And as the famous Schools Week cover makes plain, he was the great survivor. The immovable. The inevitable.

On Wednesday night, there was confidence. A new secretary of state had been appointed. But the reshuffle was not that radical. Surely Nick Gibb would continue. And yet.

For those who have made it this far – teachers especially – there may be bafflement and, perhaps, rage at those who regret his sacking. For every defender, there is an attacker. Let’s be honest, more than one.

This was a minister who, say his detractors, took a deliberately selective approach to evidence, and used it as cover for a highly ideological drive to remould English education in his own eyes. Good riddance to the man.

Read: Nadhim Zahawi appointed education secretary

In numbers: 12 facts about the new DfE boss

I’m not going to argue about phonics, or a legacy that includes ITT reform, curriculum change at all key stages, support for better textbooks and resources, or tougher exams. Really, I’m not. But my view is clear. Love him or loathe him, Nick Gibb was made for the schools minister job.

A good junior minister does a multitude of often contradictory things. He or she has to do all the unglamorous things their boss doesn’t want to – parliamentary debates at 10pm, speeches to obscure events, sitting in detailed committee stages to do line-by-line review of legislation, signing endless letters, dealing with MPs’ queries about their constituencies.

They have to appear on the media at a moment’s notice. They have to do the hard work of sweating the small stuff with officials. They are the first person who angry lobby groups go to scream at. And for most of them, they have zero – I mean none, nada, zilch – power to change anything. Most of the time, though, that’s OK, because they don’t really care about the policy area. Serve 12 months, don’t wind up No 10, move on.

Nick was not like that.

He was a rare combination of someone who cared deeply about his brief, and worked it. He outlasted secretaries of state, officials, and lobby groups. He had a clearly articulated theory of change. And he wasn’t shy about defending it. When it would have been easy to dissemble, or to brush off a question, he wouldn’t waver.

That steeliness of spirit – a belief he was right – is what drove many of his detractors mad. Was he too unbending at times? Perhaps. But taken from the other perspective, if you believe in what you’re doing, why would you bend?

Ultimately, people ought to go into politics to make a difference. And as the poet Charles Mackay said: “You have no enemies, you say? Alas, my friend, the boast is poor. He who has mingled in the fray of duty that the brave endure, must have made foes. If you have none, small is the work that you have done.”

Nick had enemies. Small is not the work that he has done. Those of us who continue the cause for education reform will be poorer for his absence.

Your thoughts