Paul Gosling, new president of school leaders’ union NAHT, tells Jess Staufenberg the government must prioritise getting exhausted headteachers back on side

Primary school headteacher Paul Gosling, the incoming president of school leaders’ union NAHT, says the title of his debut conference speech next week is “Humanity, Compassion and Solidarity”.

Noble ideals, by any standards. But during our interview, there is one word he says again and again, and it’s none of the former. Instead, he keeps talking about “agency”.

His predecessor, fellow primary school head Tim Bowen, made the focus of his one-year presidency “wellbeing”. No wonder.

The Covid pandemic has put leaders and staff through unprecedented stress and even trauma (a Teacher Tapp survey in October found almost three-quarters of heads had witnessed a colleague cry last year).

But the vice president, who officially takes up post on Friday April 29, wants to trace the crisis of poor wellbeing right back to its source. “Tim has been focusing on wellbeing, which is great. But the focus on wellbeing was dealing with the symptoms, and I want to deal with the cause.

“Rather than pulling bodies out of the river, let’s look at where the bodies are going in and why.”

The statistics on school leadership are stark.

In March last year, an NAHT report stated 75 per cent of assistants and deputies said that concerns about work-life balance were currently preventing them from seeking a headteacher position.

A union survey also found 53 per cent of deputy and assistant heads and middle leaders did not aspire to headship – significantly up from 40 per cent five years ago.

Headteacher vacancies rose by 18 per cent in the first three months of this year, compared to the same period in 2020, up from 957 to 1,125, according to teacher vacancies website TeachVac.

It’s the first noticeable rise in headteacher vacancies since Covid hit – suggesting the relentless toll of leading a school through the crisis is starting to bite.

The government’s insistence that things are back to normal again doesn’t match with the experience of leaders on the ground, who are still battling huge staff and pupil absences.

And post-Covid norms such as free testing have been ditched, while pre-Covid norms such as league tables back.

This month, the NAHT’s head of advice Kate Atkinson, warned “there is a real sense now it has all got too much”.

Gosling is clear who’s to blame. “I do think some of the low wellbeing is being driven by the way we’re treated by government. Poor mental health often comes from a loss of choice.

“Schools are humane and compassionate places, but we’re often not treated like that.”

Poor mental health comes from a loss of choice

A failure to protect the agency and autonomy of school leaders has been on the downward spiral for some time, he says, pointing to “intervention at the classroom level”, such as the numeracy and literacy hour brought in under New Labour.

But the arrival of Michael Gove as education secretary in 2010 heralded a “work harder, jump faster” approach which has “burnt people out”. It’s worse when leaders have to implement changes they don’t themselves agree with, says Gosling.

He was forced into drastic action at his own school – exactly the kind he didn’t want to implement – to meet funding challenges.

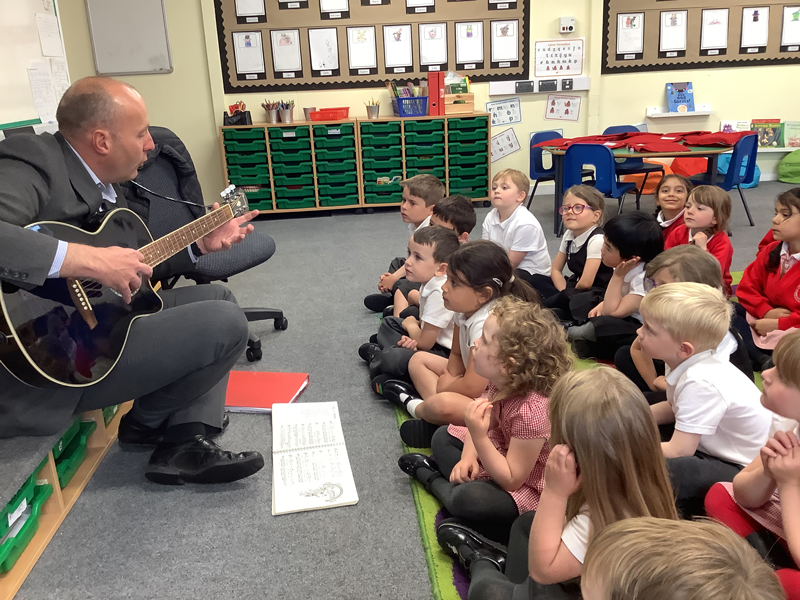

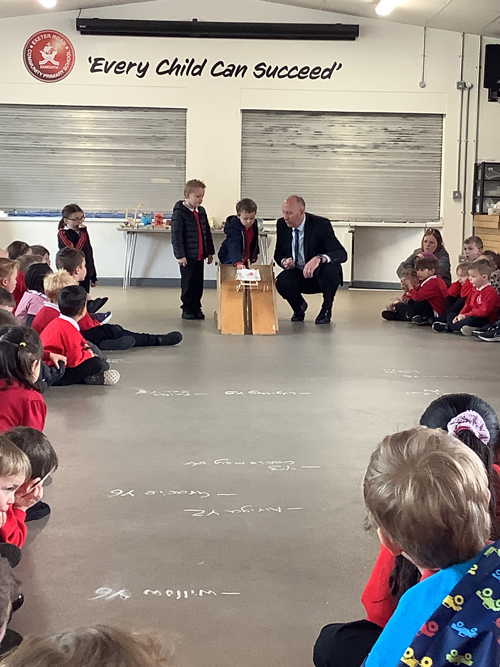

He has been headteacher at Exeter Road Community Primary School in Exmouth for 13 years now, taking it from the old ‘satisfactory’ to a ‘good’ in 2012, a grade he kept at a short inspection in 2017.

But he had been running at budget deficit for seven years.

“The local authority was very supportive. But then they said at one stage, ‘This is going to get picked up’.”

Nearly nine per cent of pupils at Gosling’s school are on an education, health and care plan, and 45 per cent receive free school meals – both well above the national averages. As a result, he was “running a very hot budget”.

“We used to have a policy that every teacher had a teaching assistant. But the high-needs money wasn’t coming in to cover the costs.” The school had to lose ten of its 24 teaching assistants. “That’s ripped the support out.”

Gosling adds: “We lost a specialist reading recovery teacher, and a maths support teacher, who did one-to-one work with children who were falling behind.

“Having those people would have been so useful during the pandemic.” He almost throws his hands up in despair. “And now the government is talking about one-to-one tuition!”

The school now has a balanced budget, but is “not the same school as it was in 2017. Is it as good? You lose that many people…”

Gosling’s frankness is all the more powerful because he comes across as a fundamentally optimistic and energetic person. None of it comes across as a whinge – he’s too good humoured. But his concerns all feed into the wider retention problems.

“You are receiving guidance and laws from the Department for Education which sometimes you don’t support totally, and you’ve got to do it even though you don’t believe in it sometimes, and that puts people off the job.

“We tend to suffer in education from neoliberal ideas of running businesses dating from the 1970s and 80s,” he shakes his head. “Look at Google today – it’s all about working with the ingenuity which comes from releasing people’s potential properly in the organisation.

“If you take away people’s agency, you take away the joy of the job and why they’re doing it.”

Compounding the problem is that a headteacher or principal can usually only turn to their deputy or assistant for support on a day-to-day basis.

“Deputies are very close to the pressures of the job. They see those frustrations, and they may think, I don’t want that responsibility myself,” he adds.

Deputies are very close to the pressures of the job

It’s what makes supportive colleagues so important for encouraging staff up the ladder – and why it is so frustrating for Gosling that he’s had to cut staff.

Despite attending a pretty “horrible” secondary school himself as a child, he was inspired to train as a teacher in Devon after doing work experience at the school where his mum was a secretary.

Meanwhile his father had left school at 15 to sell carpets on Rathbone Street Market, in Canning Town. The family was religious (although Gosling is not), and a bishop in church spotted his dad’s leadership potential.

Gosling explains with admiration that his dad eventually became a probation officer, working with young offenders caught up in the criminal gangs of east London in the 1970s and 80s.

Gosling returned to his own school, Ravenscroft Primary, in east London, for his first job, before later moving back to the west country. He became head at Exeter Road in 2009.

During his tenure, Gosling says he has experienced the government failing again and again to properly consult, or consider, the profession it oversees.

He says this includes everything from guidance arriving at 7pm on a Friday, or Ofsted claiming it would run inspections even if a headteacher had died (the statement was quickly retracted).

He says the new academisation target (for all schools to be in a strong trust by 2030) won’t happen without “proper partnership”. Will the DfE listen?

“I was involved in a roundtable with [former schools minister] Nick Gibb a few years ago, and I mentioned agency. He wrote it down in a little book. But it runs into the sand if they don’t fully understand the message.”

His advice?

“Come and talk to NAHT. We will help you understand how people are thinking and feeling. We’ll help you finesse your message. We want the best for the country, and you do too, so let’s do it.”

If the government wants to avoid an exodus of exhausted headteachers, the new secretary of state should take note.

Your thoughts