More than 100 Conservative MPs have pledged to campaign for a wave of new grammar schools, reigniting the decades-long debate on the issue of selection.

The opening of new grammar schools, which require pupils to pass the 11+ test to gain admittance, was banned by Tony Blair’s government in 1998.

But following the appointment of Theresa May – a supporter of grammar schools – as prime minister, and the confirmation by new education secretary Justine Greening that nothing is off the table, politicians are hoping to see that ban reversed.

The push is being led by Conservative Voice, an activist group launched by David Davis and Liam Fox, two former backbenchers who have gained new prominence in May’s cabinet, and more than 100 other MPs – many of them grammar school alumni – have signed up their support.

The question of whether or not grammar schools are a good thing is one of the most divisive in the education policy sphere, so we have fact-checked some of the recent claims made by those who want to see a return to the selective system set up by Butler’s education act in 1944.

Do they improve social mobility?

Don Porter, the founder of Conservative Voice, has told The Sunday Telegraph that he believes the return of grammar schools will form a “fundamental part of social mobility”. Boris Johnson is another prominent politician to have made such a claim.

But do they really improve the life chances of the disadvantaged? The short answer: not at the moment, no.

Ofsted chief inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw (right) has previously said grammars are “stuffed full of middle-class kids”, and the data does seem to back up this claim.

Research by Policy Exchange shows that, as of 2012, just three of the 164 remaining grammar schools had 10 per cent or more pupils eligible for free school meals. 42 grammars had between 3 and 10 per cent of pupils eligible for free meals, while 98 had between 1 and 3 per cent, and 21 had less than 1 per cent.

And an investigation by Newsnight policy editor Chris Cook when he was at the Financial Times shows that poor children perform worse in terms of their GCSE results in areas where there is selection.

Do they raise educational standards?

Graham Brady, a Tory MP and chair of the influential 1922 backbench committee, has said we “should only be concerned with what works not with ideology” when it comes to the drive to raise standards in education.

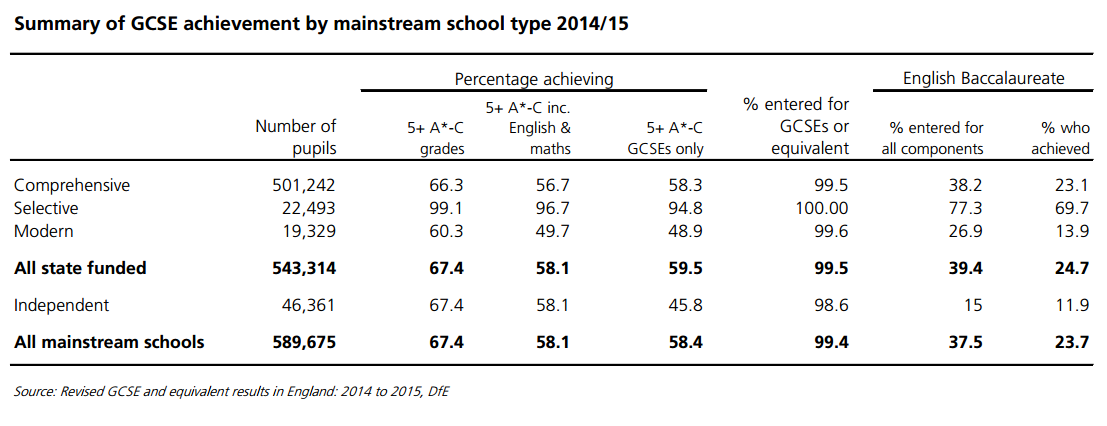

While it is correct to say that grammar schools do produce better exam results (see image below) than their comprehensive counterparts, they do not raise standards across the state education system across the board.

In 2014-15, 96.7 per cent of pupils at grammar schools got five or more GCSEs between grades A* and C, including English and maths, compared to 56.7 per cent at comprehensives.

In the same period, 77.3 per cent of grammar school pupils were entered for all components in the English baccalaureate, compared to 38.2 per cent of comprehensive pupils.

Of those entered for the EBacc, 69.7 per cent of grammar school pupils achieved the measure, compared to just 23.1 per cent of those at comprehensives.

But the same data also serves as evidence of one of the biggest problems with grammar schools – they only benefit pupils who pass the 11+, and in some circumstances they adversely affect those who don’t.

The same data shows that the attainment of pupils at secondary moderns – which are non-selective schools that exist alongside grammar schools in areas which still have selection – is lower than that of comprehensive pupils.

In 2014-15, 49.7 per cent of pupils at secondary moderns met the five A* to C including English and maths benchmark, while only 13.9 per cent of those entered for the EBacc achieved it.

By admitting the brightest pupils in a geographical area, selective schools can also have the effect of “creaming off” academic talent, leaving nearby non-selective schools with less able intakes than those of similar schools in areas without selection.

Fears have also been raised about their impact on the finances of non-selective schools.

In Gloucestershire, the heads of several comprehensive schools have expressed serious concerns about the impact of the proposed expansion of grammar schools in the area.

Could they target pupils in socially deprived areas?

The Telegraph reports that the Conservative MPs pushing for new grammars will suggest that the first 20 new schools are created in “socially deprived areas to challenge the image they are targeted at the middle class“.

This is technically possible, and one of the stated benefits of grammar schools is that they admit pupils based on ability, not where they live.

One of the biggest criticisms of the current school system is the “postcode lottery” created by school choice and catchment areas.

Although some grammar schools do have catchment areas, these tend to be wider than those of nearby comprehensives, and as a result being able to send your child to a grammar school is less likely to depend on your ability to afford to live nearby, especially if it’s in a more expensive area.

In 2014, research by the University of Bristol Centre for Market and Public Organisation, the University of Cambridge and the Institute for Fiscal Studies showed that basing admissions on how close a pupil lives to a school was a big driver of inequality between rich and poor.

BUT…

We will have to wait and see the proposals for how these 20 schools could operate. Even if they open in the most deprived parts of England, it will be difficult to establish catchment areas which do not include wealthier suburbs, especially as some of the poorest areas of the country exist within larger cities and metropolitan regions where deprivation can vary greatly between postcodes.

Skegness Grammar School is in one of the most deprived coastal towns. Yet only 11.3% of its intake in 2014/15 were eligible for free school meals in the last 6 years (FSM6). The national proportion is 29.4%. By contrast, Skegness Academy (non-selective), had 50.1% FSM6 pupils.

It does not follow that creating selective schools in disadvantaged areas that they will primarily serve disadvantaged pupils.

It also does not follow that because only 11.3% of the intake in Skegness Grammar School in 2015 was eligible for free school meals then we should just carry on with the failed comprehensive approach that has resulted in a marked drop in standards across society and a caste like system in which 7% of the population dominates. This ‘fact check’ should be examining what intake to the top universities was like before grammar schools began to close when Thatcher was Secretary of Education to Edward Heath.

Even if grammar schools could increase the number of working class children attending them a policy of reintroducing secondary modern schools for the other 80% is wrong. The statistics and anecdotal evidence regarding a system which fails children at 11 years old shows clearly that such divisiveness does not aid social mobility or enable working class children to achieve their potential.

Lets refer to the Conservative idea as “reintroducing secondary modern schools” not ” reintroducing grammar schools” as this would be the reality of selection for most of our children It would also result in an expansion of the independent sector as middle class parents paid to keep their children out of secondary modern schools.

FSM representation at Reading’s grammar schools is < 1.2% compared to 18.2% in the LA killing dead any theory that a large catchment can promote socially inclusive but it's not hard to see why. The annual child season rail ticket from Slough to Reading alone is about £1k. Add a bus journey and you double this. Reading's grammar schools accept children from all socioeconomic backgrounds; Slough, Newbury, Basingstoke, Guildford etc. but only those who can afford it! Reading School told the Adjudicator that families on benefits can claim travel costs but the LA confirmed this is only to the nearest *suitable* school and would not cover parental choice to send children further to school.

Do you have stats for a comparison between performances of poor children at comprehensives in fully comprehensive areas, and poor children at ‘non-selective’ schools in areas where there is 11-plus and grammars, e.g. Kent?