Hundreds fewer schools have been given cash for repair work as soaring building material costs mean static government funding does not spread as far, Schools Week analysis suggests.

The government yesterday published the 2023-24 funding outcomes for its Condition Improvement Fund.

The £450 million pot for repair works including new boilers and repairing roofs is available to just over 4,500 academies in small trusts, sixth form colleges and voluntary-aided schools, who have to bid for cash.

Large trusts and council schools get capital funding allocated automatically through a separate route.

Here’s what you need to know about this year’s funding round…

1. 25% drop in successful repair bids…

A total of £456 million has been handed out this year, compared to £498 million last year.

There was a drop of a quarter in the number of projects getting the go-ahead, from 1,405 last year to 1,033 this year.

It means overall this year, just a third of the 3,061 bids that were submitted were successful.

Nearly 300 fewer schools have also benefited – down from 1,129 last year to just 859 this year.

This comes despite government officials last year escalating the risk level of school buildings collapsing to “very likely”.

Of the 4,547 eligible schools, just under half (2,076) applied for cash.

2. …as building costs rise

The average project cost rose from around £350,000 last year to £440,000 this year.

This is likely because the CIF funding pot remained static against a backdrop of rising material and labour costs, said academy funding consultant Tim Warneford.

The price of building materials rose by 10.4 per cent in January compared to a year earlier, government figures show.

This followed an increase of 11.2 per cent in December 2022 compared to December 2021.

3. Which schools were most successful?

For the first time, government has provided information on bids by geography, phase of education and type of project – meaning we have lots more detail this year.

Of the 1,033 successful bids this year, just over half were primaries (56 per cent), roughly a third were secondaries (36 per cent) and five per cent special schools.

Nationally, primary schools make up just over three-quarters of all state schools and secondary schools account for around 17 per cent, government statistics show. However, secondaries are generally much larger buildings.

The CIF phase of education statistics show secondary schools were more likely to apply for cash (56 per cent of those eligible), with 45 per cent of those applying successful.

This was higher than primary schools (which had a 39 per cent success rate) and similar to special schools (45 per cent).

4. South west schools least likely to get cash

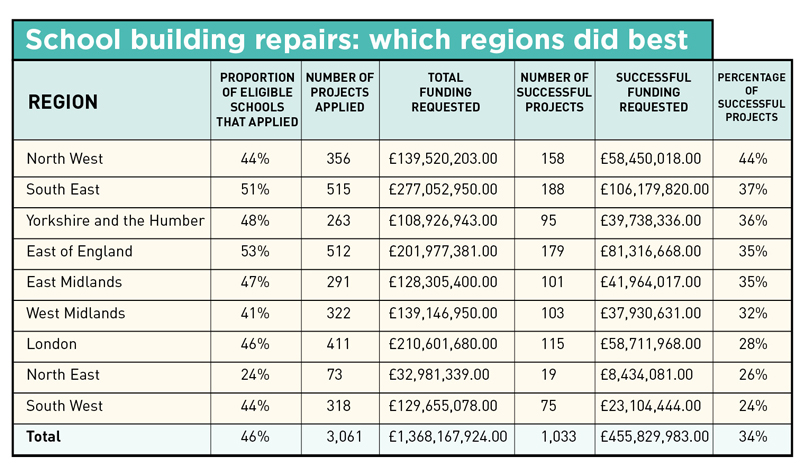

Schools in the south west were least likely to win funding with just 24 per cent of bids from schools in the region successful, followed by the north east (26 per cent).

The north west saw the largest proportion of bids successful (44 per cent).

By funding amount, schools in the north east got £8.4 million while schools in the south east got £106 million.

5. Repairs ‘won’t make major contribution’ to wider landscape

Schools Week searched popular building work terms to get an idea of what the cash was going towards.

Projects seem to be named based on what was written on the application, so there isn’t uniformity. But it still gives us an interesting insight.

For instance, 373 projects (36 per cent) had the word ‘urgent’ in them. Nearly 200 were for work to repair roofs. Schools Week reported in 2019 how two-fifths of schools had buckets catching drips from leaky roofs, a survey suggested.

Around 200 related to boilers and heating, and 219 related to ‘fire safety’. Just six works had the term ‘RAAC’ in them.

Building experts have called RAAC – which stands for reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete – a “ticking time bomb” leaving schools “liable to collapse”.

Our investigations found nearly 200 schools had or were suspected to have it. Government officials have urged schools to check for the material.

“The focus, in terms of the types of awarded projects, addressed risk to life, through fire safety and safeguarding, risk to school closure for life expired heating and hot water systems and key fabric, such as roofs,” Warneford added.

While this will “make those schools safe, warm and dry, it will not make a major contribution to the wider school estate landscape”.

Repairing or replacing all defects in England’s schools will cost £11.4 billion, the Department for Education said in 2021.

6. 1 in 8 awards for schools which coughed up lots of cash

Government has also published how many projects were successful based on the size of the financial contribution they pledged.

Schools can only get full marks on the funding section of their bid if they pledge to pay more than 30 per cent of the work either out of their own pocket or via a loan, rather than relying fully on grant funding.

However, interest rates for loans, via the Public Works Loan Board, have shot up from around 1 per cent to around 5 per cent for this year.

The DfE stats show that around one in eight successful bids were where schools were willing to stump up over 30 per cent of the costs themselves.

Of the successful bids, 22 per cent had contributed between 10 to 15 per cent while 21 per cent had contributed under five per cent.

Warneford said the drop in awarded projects also reflected a “reduction in trust’s financial wherewithal to support their bids and for the ESFA to cross subsidise other applications that meet their most urgent criteria but where there was no financial contribution”.

He cited the rise in interest rates, including inflationary spending pressures like energy costs alongside reduced school budgets and reserves impact schools’ ability to meet the affordability criteria.

Your thoughts