From California’s Death Row to school governance, the Confederation of School Trusts’ Samira Sadeghi explains how the roles are more linked than you might think.

When Samira Sadeghi is delivering training to support sector leaders getting governance right, she explains how insights gleaned about human fallibility from her time working as a lawyer on death row can help.

The eight prisoners Sadeghi, director of trust governance for the Confederation of School Trusts, represented during her twelve-year legal career on California’s Death Row “almost without fail” had one thing in common. They had all experienced “pretty major traumas” before the age of three – the most important time for brain development.

The trauma left their prefrontal cortexes “severely compromised”, she says, meaning their “impulse control was gone, and they were left on edge and stressed”.

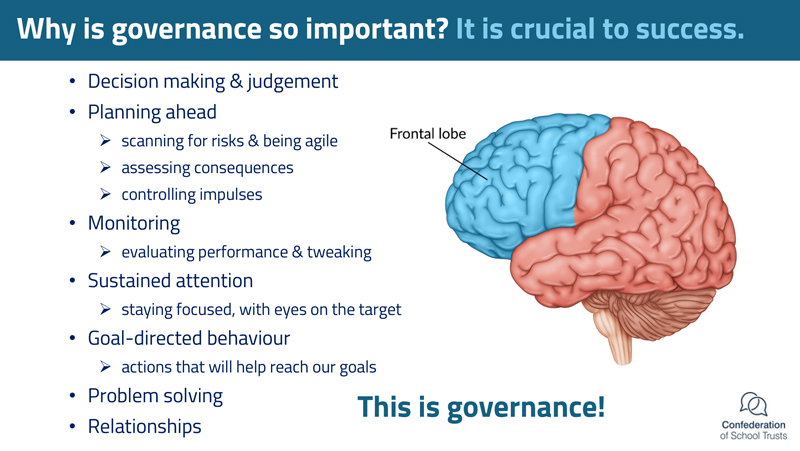

There’s a “direct parallel” between the prefrontal cortex and school governance, Sadeghi adds, as both are where “decision making, monitoring your performance, problem solving, planning ahead, and goal-directed behaviour come from”.

As with governance, when these elements “function poorly”, it becomes “very difficult to succeed”.

Human rights passion

Sadeghi’s desire to work in human rights came after two of her uncles and an aunt were imprisoned for attending political rallies in Iran, where she lived as a child for six years.

Her extended family are well-educated (most of them are doctors) which meant when revolution broke out in 1979, they were able to “rebuild their lives abroad”.

Her immediate family returned to America, where Sadeghi was born, and settled in Los Angeles.

Studying political science at the University of California, she spent a year at the UK’s University of Exeter, where she met her future husband.

She stayed to complete an international history masters at the London School of Economics, before joining human rights organisation Amnesty International on an internship. Tasks included sifting through “horrible” photographs of torture and extrajudicial killings in Guatemala and writing posts about political prisoners – many of whom were Iranian.

After moving back to San Franciso with her partner, Sadeghi studied law and joined a project working with prisoners on Death Row at the city’s San Quentin prison.

She became “fascinated” with her task of telling the “incredibly rich, powerful and compelling” life stories of those she represented.

“When you humanize someone by telling their story, people feel they understand them and it’s a lot harder to kill them.”

Life stories on Death Row

Three of the prisoners had spent their entire adult life incarcerated. To extract their stories faithfully, she had to learn “how to be comfortable with silence, and ask open questions” (she normally “talks nonstop”).

She would take in popcorn on her prison visits. “Any treat they got came from us. They loved being able to interact with another human.”

Her first case was an 18-year-old jailed for three murders in quick succession, two of which were drug related. Two days after her last day in the job, the court finally granted him a hearing for a claim on the grounds of intellectual disability. But four years later, he was resentenced to life in prison.

“There are no winners in Death Row work … It’s such a painful thing to imagine someone living in a 8ft by 4ft box for the rest of their lives, as a result of having … experienced such horrendous acts of violence against them as a child that it warps their ability to behave within our societal norms.”

Identifying the path from trauma to criminal behaviour prompts Sadeghi to worry whether teachers are being “trained enough on how to spot trauma induced behaviours”.

“When a kid comes across as not having any remorse or impulsivity, there could be a trauma basis for that”. She cautions that “an authoritarian attitude” will “just make that behaviour worse”.

Moving upstream

Death Row work was “never a 9 to 5 job” and she quit to “make up for lost time” with her two children, then three and six.

After they moved to London in 2010, Sadeghi became a governor at her kids’ school, Ark Academy. It led to a job as Ark’s regional governance officer.

She sees the career move as akin to a quote from Desmond Tutu: ‘There comes a point where we need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they’re falling in.’

During four years at Ark, she noticed how the “traditional school governance model that worked for a single maintained school has been superimposed on trusts”.

Academy trusts have a board of trustees who, like maintained school governors, set the strategic vision and look over financial performance – but across the wider trust instead.

However, each academy still has a governing board, and the sector still seems to be grappling with exactly how these should operate most effectively.

Sadeghi believed back then, and still believes now, that governance needs “to be completely reimagined”.

When she joined Academies Enterprise Trust as its head of governance in 2020, she set about doing just that. Then one of England’s biggest trusts, AET had been in “really bad shape”, which Sadeghi blames partly on it being “too big” and “so spread out” geographically.

The then new chief executive, Julian Drinkall, who hired Sadeghi, had controversially removed all local governing boards and brought in paid chairs, declaring that “playground bully parents” would no longer be allowed on boards, only those with educational expertise.

Sadeghi understood his motives for the “command and control” approach. “He had to turn things around quickly, and needed educationalists monitoring the situation.”

Academy councils

But, she started to overhaul the model after new chief executive Rebecca Boomer-Clark took over the trust in 2021. They launched 56 new ‘academy councils’ in six months, reinjecting boards with a community focus that included two elected parents, up to two employees and a council representative.

Sadeghi believes at the trust local level, it’s “really important to get rid of the word governor, which is outdated because it’s not about governing … we are conveying that their role is the same as in a maintained school, which it isn’t”.

Some trusts are doing this. Examples include advisory board members, council members, and champions.

Sadeghi says those in the role can help trusts “understand that school’s community, so we can contextualize our strategies to make sure they’re anchored in that community.”

At AET, those who had previously sat on governing boards were invited to join the new councils. Although “some chafed because they were used to being able to make certain decisions”, the ones that AET retained were mainly local people who “bought into the idea”.

Governance image problem

Sadeghi joined CST in September to run one of its ten professional communities, with hers representing trustees and governance leaders. She loves the role which involves “getting to indulge in fascinating things” from local governance to attendance, and ethical leadership.

The ‘reimagining governance’ sessions she runs encourage attendees to “throw everything you know out the window”.

She believes doing so can help with governor recruitment, which is in dire straits (a record 77 per cent of governor boards told the NGA last year it was an issue).

Governance “suffers from an image problem [of] a bunch of old white men sitting around a table with agendas and minutes and policies”.

Some governor descriptions also sound “boring – I wouldn’t want to do it. But if you posted a job role that involves partnering with the community and developing relationships with organisations, that would really appeal to me.”

She believes that trusts, including headteachers, should be out headhunting in their local communities for board members. That could mean asking “the guy who owns the business across the street from the school. We need to be recruiting in a totally different way for different people.”

There are signs the DfE agrees on the change agenda. Last week, it published two separate governance guides, tailored separately for maintained schools and trusts. “Hallelujah!” Sadeghi says.

And getting governance right is more important than ever, she adds, given that relationships with parents have “gone completely sideways”. CST has warned that the recent rise in complaints is “not sustainable”.

Governance culture shift

Sadeghi says if she can help enact culture change in the education sector, it will overtake her work on death row as her proudest achievement.

She believes progress has been hindered by “too much thinking about reputations … The focus should be on what is good for the children and adults in your organisations.”

She adds the sector more generally needs to be “less adult-centred and more child and community-centred”.

For example, she questions whether, “when schools cite ‘loss of autonomy’ as the reason they don’t want to join a larger trust, is that decision based on the children or the adults?”

But she thinks the sector is working hard on that shift.

She was on the steering group behind the Academy Trust Governance Code, launched in October 2023 to “enshrine principles around how to behave – to be open, transparent, collaborative, and meaningfully engaged with your community and stakeholders”.

She believes that the code, which is “voluntary and aspirational”, will bear fruit where it is implemented, providing “a voice for all stakeholders at all levels, greater public confidence in our schools, and enable trusts to reclaim their role as institutions anchored in their communities”.

Your thoughts