More than one in three Teach First recruits are now either career changers or school support staff nominated to join the scheme, as the charity shifts its focus away from targeting elite university graduates.

The teacher trainer’s new strategy, seen by Schools Week, also outlines a push into professional development to help its alumni into school leadership.

Set up in 2003, Teach First was tasked by the government with recruiting “exceptional graduates with high academic ability” who might not have considered a teaching career to work in schools serving the most disadvantaged communities.

Speaking to Schools Week, CEO Russell Hobby says that recruiting “the top talent in the country who maybe are not convinced of a career in teaching” is still Teach First’s unique selling point. Narrowing the attainment gap remains its core mission.

But “it’s not just about top graduates”, Hobby insists.

Rise of the Teach First career-changer

While the new strategy document setting Teach First’s direction for the next six years continues to refer to recruiting “high potential future teachers”, it makes no reference of graduate recruitment.

The previous strategy talked of recruiting “large numbers of new and recent graduates”.

Almost a quarter of the latest cohort were career-changers, up from 21 per cent last year. More than one in 10 were teaching assistants or others known to schools who were nominated to join the scheme.

The shift comes as Teach First aims to reduce reliance on its hefty government contract, worth around £39 million per cohort, or £22,000 a teacher.

Five years ago, it was responsible for over two-thirds of its income. Now it forms less than half.

But some ambassadors privately fear that the new direction – and broader definition of “high potential” teachers – will dilute its justification for the higher level of government funding it gets compared with other teacher trainers.

Oxbridge degree no ‘cast iron predictor’ of good teaching

The charity has also faced criticism for elitism over focusing on “high potential” applicants from top universities such as Oxford and Cambridge.

But Hobby says: “I don’t think you can reliably say that a first-class degree from Oxbridge is a cast-iron predictor that that person will be an absolutely stunning teacher down the line.

“I’ve got nothing against people with first-class degrees from Oxbridge universities, I’m one of them.

“But you’ve got to know that that’s just a proxy for what you are looking for – which is smart, energetic, dedicated, believing in that subject area. You can find that in all sorts of places as well.”

He adds that “academic knowledge and subject specialism is a key foundation of being a great teacher”, but said it was a “mistake to believe that you can only find those [attributes] in top grads from elite universities”.

But there are still “plenty” of top graduates in recent Teach First cohorts. Those recruited directly from university still make up the majority. The proportion with first or 2:1 degrees has remained constant at between 95 and 97 per cent since 2008.

‘It’s healthy not to be complacent’

But withdrawal of the contract is “always a possibility”, Hobby says, adding that it is “quite healthy as an organisation to accept that possibility and not be complacent around it, too”.

“I think there are some really unique things that we bring to bear as an organisation. That brand on campus, that knowledge.

“People join Teach First. They don’t apply to the ‘high potential ITT’ programme. That has been built up over 20 years of investment. I think that’s very powerful.”

Since launch, Teach First has trained 16,000 teachers. Alumni include charity founders, senior civil servants and even MPs.

Hobby believes there will “always be a need for what we do. It’s up to us to demonstrate that we are the right people to do it.”

He adds: “We would hope we always have a relationship with the government on what we’re doing here. But there are many ways of preparing people to teach.”

‘We don’t have to do everything’

When Hobby, a former general secretary of the NAHT school leaders’ union, joined Teach First, he took the controversial decision to slim down the organisation’s focus to concentrate on teacher training.

It closed the widening participation schemes Futures and Oxbridge, and cut loose organisations it had previously “incubated”, such as the Fair Education Alliance and its Innovation Unit.

He believes this was “absolutely the right thing to do”.

“Take the FEA… It’s thriving now. We don’t have to do everything.”

Changes to the organisation have continued. Last year, Schools Week revealed that the charity had made half of its eight-strong executive team redundant. In February it began consulting on a second round of redundancies.

The organisation said at the time that it had “grown rapidly” to offer things like NPQs and the ECF, and “to consolidate this growth, and prepare for the future, we are proposing changes to how we operate”.

New leadership push

Despite cutting its cloth, strategy documents reveal some big targets. On top of its recruits via the “high potential” route, the charity aims to recruit 4,000 teachers by 2030 through its new, school-centred initial teacher training (SCITT) programme, which opens in September.

But Hobby does not believe Teach First “will ever be a standard teacher training provider because we’re just not needed for that. There are good teacher training organisations out there.”

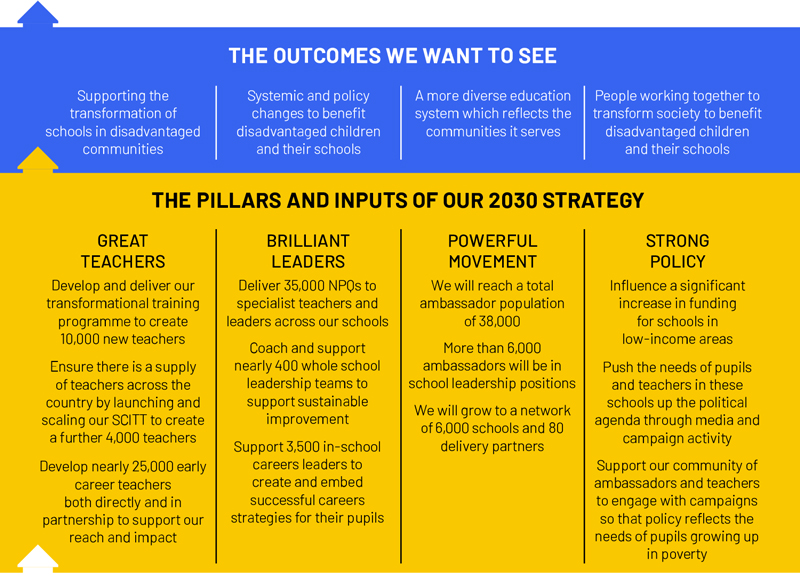

It also wants to swell its ambassador population to 38,000, with 6,000 in school leadership positions, and to grow its network to include 6,000 schools.

“We want to focus more on leadership, and how we help our people on that journey through both into school leadership positions and into other positions of influence in society as well,” Hobby adds.

‘Depth not breadth’

The charity is delivering the full suite of national professional qualifications (NPQs) for leaders and is also designing its own development programmes using increased charitable donations from partners.

These include Leading Together, a two-year development programme that is free for schools.

It plans to deliver 35,000 NPQs and coach and support nearly 400 school leadership teams by 2030.

Hobby says the greater emphasis on professional development is not a return to the “breadth” of its past offer. “I’m talking about depth. This growth is stacking up on top of itself rather than diversifying out in that sense of it.”

Like the sector more widely, Teach First faces recruitment issues. This year it recruited 1,335 trainees, missing its government target by more than a fifth. However, recruitment on all routes into teaching was 38 per cent short of the target.

It has done things like trialling £2,000 cost-of-living grants for trainees. It also intends to offer the government’s new teaching apprenticeship for non-graduates to widen its recruitment pool.

‘Freedom to speak truth to power’

More widely, Hobby sees Teach First’s mission as a “pillar” which “begins with great teaching”, then moves on to leadership in schools, with its ambassadors becoming a “community that works together” both inside and outside education to influence policy.

“Those are the four strands of what we do and I think they are all built on top of each other, because it’s the teacher who becomes the leader who joins the community – and it’s the community that influences the system.”

While many ambassadors did not want to speak about the strategy, Loic Menzies believes the strands of impact are a “welcome acknowledgement that Teach First can’t deliver on its mission around educational equity solely through classroom teaching”.

“Now that the charity has reduced its dependence on its core government contract, it should have a bit more room for manoeuvre in pursuing those priorities – as well as some more freedom to speak truth to power,” he says.

Teach First’s strategy gives a nod to that. The charity wants to influence a “significant increase” in funding for schools in low-income areas, “push the needs” of pupils and teachers in these schools and support ambassadors and teachers to “engage with campaigns so that policy reflects the needs of pupils growing up in poverty”.

Hobby adds: “What the government wants is people who will be brilliant teachers who would not otherwise teach. I am pretty confident that, if it gets them, everybody will be happy.”

Your thoughts