Companies backed by private equity investors and a Middle East sovereign wealth fund running private SEND schools have made millions in profits amid a state capacity crisis.

The firms – many of which also run children’s homes – said they provide high quality education filling a “significant shortfall” in provision, meaning pupils with special needs are not left behind.

But, average independent special school costs are double that of the state sector, analysis suggests, with some councils unable to afford recent increases.

One analysis estimates some companies are making tens of millions of pounds in profit, with one director paid £1.1 million last year. Some are registered in tax havens.

While government is telling some cash-strapped councils to rein in their spend on private schools, the state’s sluggish response to demand means they are locked into a “circle of financial doom”, said national SEND leader Warren Carratt.

“The government’s failure to effectively plan for – and adequately invest in – the increased demand has left some providers in the independent sector making eye-watering profits at the expense of already hugely overspent high needs budgets,” he added.

“Meanwhile, government guidance is in turn allowing and enabling state special schools to have their budgets reduced – leaving an ever-increasing role for the independent sector.

“It is a damning indictment of the free market principles that – as with independent children’s homes – are holding our public sector budgets to ransom and moving our councils and state special schools toward bankruptcy,” he said.

Private school spend soars

The combined deficit for councils with high needs funding blackholes was £1.59 billion as of March 2023, according to analysis from the Special Needs Jungle website.

Yet councils spent £1.3 billion on independent and non-maintained special schools (NMSS) in 2021-22, more than double the £576 million spent in 2015-16, government data shows.

The number of pupils at these schools has risen by 52 per cent over that time, as an explosion in pupils with additional needs outstripped capacity in the state sector.

However, the average cost of an independent and NMSS place in 2021-22 was £56,710 – more than double the £23,224 average cost of a place at a state special school, Schools Week analysis found.

In its 2022 SEND green paper, the Department for Education said this was because such schools often cater for pupils “with very complex needs”.

But they also said capacity pressures in the SEND sector mean more children are being placed in private special schools “even when this may not be the most effective setting for them, resulting in poor value for money”.

Government has recently told some councils to rein in such spend as part of its “safety valve” scheme. Thirty-four councils with the largest high needs deficit blackholes have been given government bailouts totalling nearly £1 billion.

Spending on private SEND schools among the 23 safety valve councils that responded to our freedom of information request rose by 43 per cent from £210 million in 2018-19, to £301 million in 2021-22.

Surrey’s costs rose from £48 million to £74 million in that period. In 2022-23, they topped £86 million. Kent’s has risen from £34 million to £67 million this year.

Sluggish state creates gap in market

In January, Bury council said its specialist provisions “are full” meaning “we have been forced to place significant numbers” in the independent sector, where its spend rose from £5.3 million in 2018-19, to £10.6 million in 2022-23.

Nationally, the number of youngsters with education, health and care plans – a legal document that sets out extra support a pupil must receive – has risen by 46 per cent since 2018-19, from about 354,000 to 517,000.

However, delivery of new state special schools has not kept up. Schools Week revealed last year how just one of 37 new free schools announced in 2020 had opened in its permanent home. Six first approved in 2017 were still yet to open.

There were 712 independent and NMSS schools in 2022-23, up from 547 in 2018-19.

SEND consultant Barney Angliss said companies have been given “an opportunity to step in where the system is failing”.

Firms ‘agile and responsive’

Firms can set up new provision within 12 to 15 months and are “very agile and responsive” to demand, said Claire Dorer, chief executive of the sector body the National Association of Special Schools (NASS).

Outcomes First Group, one of the largest private SEND school providers, is working with councils that had bids for new special free schools rejected. Last year, government approved fewer than half of the 85 applications by local authorities.

A spokesperson for the firm said its work “helps LAs meet the significant shortfall in provision for the children that we educate, who without our specialist provision, would be left with no option but to remain out of education … Without this provision, LAs would not be able to educate these children, which they are legally mandated to do.”

Government is investing £2.6 billion between 2022 and 2025 to increase special school and alternative provision capacity. But SEND specialist Matt Keer said it’s still “not happening fast enough”.

Councils ‘unprepared’ to pay fee rises

Schools forum documents for Bury council state the average independent special school fee increased by approximately 10 per cent in the last year “as these schools look to pass on cost increases”.

September schools forum documents for Merton, Southwest London, reveal that their non-maintained special schools are “asking for very high fee uplifts, many of which we are unprepared to pay”.

Sheffield, which is not in a safety valve agreement, said this year that the average independent place now costs £70,000, with the highest £111,000. This was a “significant pressure” on high needs allocations and a seven per cent increase in a year.

Our analysis found the average cost of a private school placement rose by eight per cent between 2018-19 and 2021-22. However, the average state school cost rose by 15 per cent – although they remain significantly lower overall.

But Dorer said independent special schools “are still the placement of last resort … too much of the time”.

“When you place a young person at 13 or 14 who has just seen needs go unaddressed for year after year, it is going to be more difficult and more expensive to affect a change with them.”

Meanwhile, at Outcomes First Group, they have class sizes of between three to 10 pupils, with one teacher to every two children. The ratio is about one teacher for every six pupils in state special schools and pupil referral units, according to government workforce data.

Carratt, chief executive officer of Nexus MAT, added most state schools have been “hand to mouth for the best part of the last decade”.

However, 89 per cent of state special schools are currently ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ – above the 81 per cent of special independent schools that are inspected by Ofsted.

Firms make millions from ‘fragmented’ sector

To get an idea of the main providers of independent SEND provision, we asked the “safety valve” councils for their individual placement costs.

Of the ten providers that received the most money from the 22 councils that responded to our FOI, five were owned by offshore companies. Three are owned by private equity.

Another is owned by an Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund. A further three were charities.

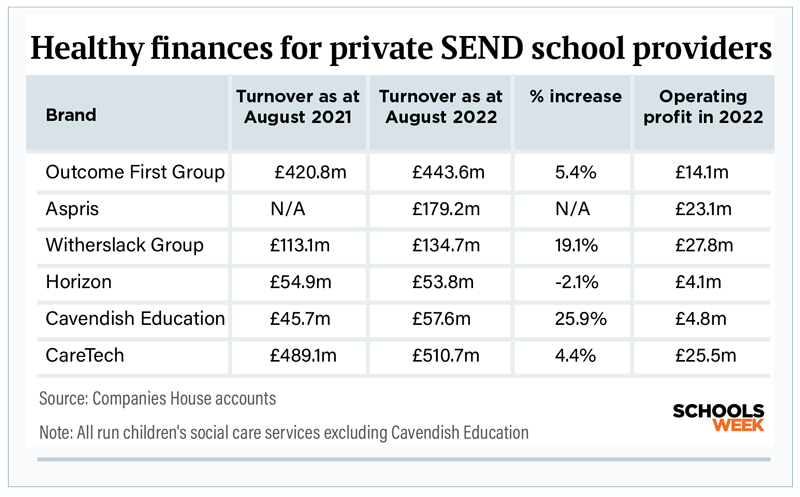

It is difficult to establish how much profit firms are making from the SEND sector alone, as many also provide children’s social care placements.

But, a report commissioned by the Local Government Association on children’s social care this year estimated four of the companies in our analysis made £184 million in profit in the last reporting period alone (see box out).

The profits relate to wider children’s services income, but would include SEND provision.

Dorer said while companies are making profit, they “all have to bear a loss while they are setting up new provision, and they are bearing a considerable risk”.

However, John Pearce, Association of Directors of Children’s Services’ president, said there are similar “concerns” to the “profiteering, costs spiralling and lack of control the local authorities have over the whole system” as seen in the children’s home sector.

Who are the firms making millions?

Outcomes First

Outcomes First Group recorded £445 million children’s services income across its last two sets of accounts, according to LGA’s analysis, put together by Revolution Consulting in September.

The company’s EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) figure was £93 million, the analysis claimed.

Andrew Rome, the report author, said EBITDA is one of the most widely used measures of profitability. His analysis found Outcomes had a profit margin of 20.9 per cent.

According to our FOI figures, Outcomes First Group and its brand Acorn Education received a combined estimate of £81 million within the last six years from the 22 safety valve councils that responded.

The group, which has 56 schools in England and also runs children’s homes, was acquired by private equity firm Stirling Square Capital Partners in 2019. Its ultimate controlling party is in Jersey.

A spokesperson said they have “never paid a dividend to any shareholder, reinvests all profits into opening new schools and all taxes due are paid in the UK”.

Witherslack

Witherslack, which runs 24 schools as well as therapeutic learning centres and children’s homes, recorded the largest profit margin of 26.5 per cent, according to the LGA report. It had an income of £148 million.

Mubadala Capital, a subsidiary of Abu Dhabi’s second-largest sovereign wealth fund, owns the company. It was acquired from private equity firm Charme Capital Partners in 2021. Witherslack received an estimated £30 million from the councils within the last six years, our FOI found.

The company did not respond to requests for comment. But a 2021-22 annual report from the Witherslack Group said all profits are reinvested as capital expenditure. The company told The Times last year that “its structure was not designed to avoid paying tax”.

Aspris

Aspris was set up by Waterland, a Dutch private equity firm, when it bought The Priory Group in 2021 for £1.1 billion. It runs 34 specialist schools and colleges in the UK as well as children’s homes.

The most recent accounts for Aspris Holdco Limited show that the highest paid director received £1.1 million, including a one-off award of £305,000 “relating to the exceptionally high level of corporate transactions and reorganisation activity successfully completed during the period”.

According to the FOI figures, it has received an estimated £33.7 million from cash-strapped councils. The LGA report suggests the firm has an EBITDA of £47 million, a 25.1 per cent margin. The firm declined to comment.

The Cambian Group

The Cambian Group, owned by CareTech, runs 34 schools in England and Wales. Last year, The Times reported CareTech sent more than £2 million to its founders’ offshore company in the Caribbean while accepting government Covid support.

Lawyers for two brothers who founded the company told the newspaper they “pay all their UK tax due” and make “significant social and economic contributions to charitable causes”.

Last year’s LGA report found CareTech’s EBITDA to be £83.8 million, a margin of 27.3 per cent. But this year’s analysis doesn’t include the firm, partly because it delisted from the stock market. The company’s ultimate controlling party is incorporated in Jersey.

The most recent accounts for CareTech Holdings Limited show an operating profit of £25.5 million and a net profit of £6.5 million.

Using just the net profit, it means the profit margin was 1.3 per cent, a spokesperson said. They added that CareTech “provides a much-needed education for children” with SEND.

But Anne Longfield, former children’s commissioner, said these “eye-watering levels of profit” are “indefensible, in my view. It’s taking money out of our statutory services at an alarming rate.”

Councils ‘hamstrung in their efforts’

The Competition and Markets Authority said in 2021 that the UK had “sleepwalked” into a “dysfunctional children’s social care market” with councils “hamstrung in their efforts to find suitable and affordable placements” in children’s homes or foster care.

It said the largest private providers were “making materially higher profits, and charging materially higher prices, than we would expect if this market were functioning effectively”.

Independent SEND school provider Aspris – set up by Dutch private equity firm Waterland – stated on its website that “surging demand” is “undersupplied by the existing and fragmented capacity, which in many cases is also dated, under-invested and not fit for purpose”.

The most recent accounts for Witherslack Group added it is continuing to “expand successfully” with new school and children’s home openings “well received” by councils.

It is “particularly strengthened” by its expansion into new areas, “much of which has taken place in response to requests by local authorities”, although it’s not clear if this is just for schools.

A £7.1 million rise in profit after tax was “reflecting the increased capacity of the company”, its latest annual accounts state.

Outcomes First Group has opened 18 new schools or extended others with 1,800 new desks in the last year alone. It plans to deliver the same expansion again over the next two years.

So what next?

But Meg Hillier, chair of the public accounts committee, said pressures on local authority spending for independent places “remain prohibitive” and leave councils facing “impossible choices and, too often, leaving children without the full support they need”.

Ministers’ SEND and alternative provision implementation plan, published in March, pledges to “re-examine the state’s relationship with independent special schools to ensure we set comparable expectations for all state-funded specialist providers”.

A “fragmented” management based on councils’ individual pupil placements “is inefficient” and “makes it difficult to assess the overall impact of independent special schools”.

The Department for Education is now considering how these schools should be aligned with new national SEND standards to “define the provision they offer and bring consistency and transparency to their costs”.

Carratt added the “biggest risk” for state schools is that councils “can’t control what independent schools charge”.

He said this risks councils directing more state schools to take children they cannot accommodate – to avoid the costs of an independent place – and state schools get reduced funding because of “independent placements negatively impacting” the high needs funding “bottom line”.

Councils ‘need powers’

The green paper did propose independent schools would be included in the new national tariffs – rules on prices that commissioners would use to pay providers. But it is not known if this will go ahead.

An LGA spokesperson added councils “need to be given powers to lead local SEND systems effectively and hold schools to account for levels of inclusion”.

In the meantime, several councils have been told to reduce their spend.

In return for £142 million to eliminate its deficit in 2027-28, Kent must “implement models of reintegration of children from special/independent schools to mainstream where needs have been met”. Norfolk has been told to agree an “inclusion charter” with schools in return for £70 million by 2028-29.

It should help mainstream schools to support “a greater complexity of need” so they are “stepping back from the over reliance” on the costly independent sector.

Firms step in as SEMH needs soar

Some of the biggest children’s social care providers are stepping in to meet soaring demand for specialist social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) schools amid a mental health crisis and increased behaviour challenges, writes Jessica Hill.

SEMH is a relatively new subset of SEND, which replaced the term emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD) in the 2014 reforms.

There are 1,015 SEMH schools in England, including 339 academies, 396 maintained schools and 229 independent SEMH schools.

Public data on these schools doesn’t include open dates. But analysis found around 50 of the 63 independent education settings, which includes alternative provision, proposed to open and pre-inspected by Ofsted since 2021 cater for children with SEMH needs.

Meanwhile, the state sector has been opening fewer SEMH schools every year, dropping from 17 opened in 2016 to six so far this year.

The top five biggest children’s social care providers now operate 104 SEMH-associated schools.

All five – Outcomes First, Polaris, Aspris, CareTech and Witherslack – have a majority or minority private equity or sovereign wealth fund owner.

Your thoughts