Government has listened to desperate pleas of leaders for more funding. But an extra £2.3 billion a year is unlikely to solve all of schools’ funding woes.

Schools Week looks at whether a ‘magic formula’ to link finances and curriculum can bring savings while also increasing standards …

Integrated curriculum financial planning has been around for years. But with schools having to hack away at their spend during times of austerity, the government has increasingly seized on its benefits.

Lord Agnew, the former academies minister, made it his “personal priority”. Its use is now baked into the system, with the academy handbook encouraging trusts to adopt it.

Put simply, integrated curriculum financial planning (ICFP) lets schools work out the core costs of running their curriculum.

There are several models, but most focus on a few key metrics, such as teacher contact ratio and class size.

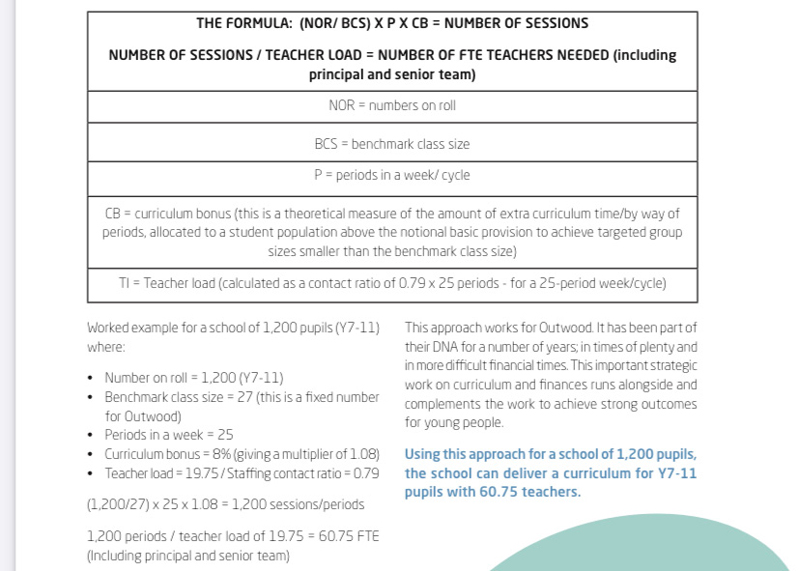

Outwood Grange Academies Trust’s model, now used and adapted more widely, involves planning the curriculum first – the ideal number of maths classes, class sizes, etc – and adapting finances to achieve it.

If the model is too expensive, you can toggle the key metrics, such as increasing staffing contact ratios, to see what is affordable.

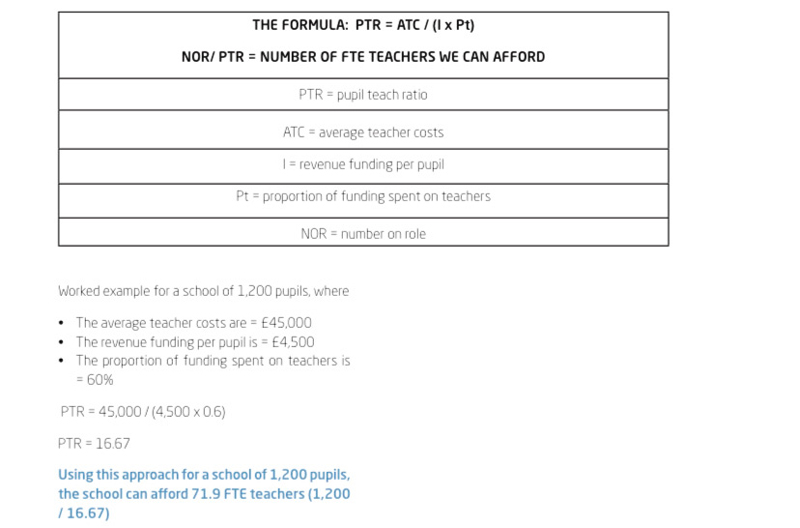

A second popular “Equation of Life” model, developed by the Association of School and College Leaders, starts with what is affordable and fits the curriculum to that.

Sam Ellis, its developer, says it helps schools “make the most of what you’ve got by working in the most efficient way… even if it’s far short of what you want to do”.

It undoubtedly saves money…

ICFP was not developed as a cost-cutting tool. Outwood Grange (OGAT) says it has been “part of its DNA” for years, “in times of plenty and in more difficult financial times”.

But it undoubtedly helps schools to deliver their curriculum for less, essentially by ensuring efficient staffing.

For instance, a key plank of OGAT’s model sets the contact ratio for all teachers at 0.79. But headteachers and deputies must be included in the average – everyone has to do some teaching for it to work.

Essentially, 79 per cent of teachers will be teaching at any one time, with the other 21 per cent off timetable.

Paul Tarn, who helped to pioneer the approach at OGAT but who now leads the Delta Academies Trust, says it has delivered “great success financially”. with in-year surpluses peaking at almost 10 per cent of funding during Covid.

He credits this partly to delayed capital works, but mainly to using ICFP across its secondaries.

Writing for Schools Week in 2019, Tarn estimated using Delta’s metrics nationally – classes averaging 27 pupils, salaries averaging £50,000, including on-costs, and staff teaching just under four days a week – could save secondaries at least £1 billion.

A more recent calculation shows similar findings.

Jonny Uttley, the chief executive of The Education Alliance Trust, says the approach has “underpinned” the trust’s strong financial health for some time.

It returned a secondary in special measures with a projected £2.5 million deficit to surplus by “realigning the timetable and better financial planning”. Teacher numbers fell, but through staff “leaving naturally”.

The Department for Education does not collect evidence on such savings as it would be “difficult to attribute to the use of ICFP alone”, however.

…But is it just cuts? (And what about standards?)

Lee Miller, a government troubleshooter and deputy chief executive of the Thinking Schools Academy Trust (TSAT), says “reducing costs and raising standards may seem like opposing forces to some”, but they can “work in a mutually-supportive way”.

Before it joined TSAT in 2015, the government issued The Victory Academy’s predecessor school a financial warning amid “significant concerns” over its deficit.

Miller says problems were “almost entirely down to a staffing structure that did not match its curriculum”. The trust, which uses its own ICFP model, reduced costs by more than £2 million in three years.

But it also improved standards – with the former ‘requires improvement’ school now rated ‘good’.

Others also point to OGAT’s and Delta’s track records turning around failing schools as evidence ICFP does not conflict with boosting standards.

‘It’s not painless – and is prescriptive’

Core Education Trust cut nearly 18 teaching posts – saving just over £1 million – after implementing curriculum financial planning across its four Birmingham schools.

“If we hadn’t gone down this route, we would have been in big trouble now,” says Jo Tyler, its chief operating officer. Rather than a projected £3 million deficit, the trust has balanced the books.

She describes the approach as planning based on “what you need first, rather than ‘here’s what I’ve got’”. While it allowed “equity” across schools, she admits it was “not painless”.

The trust had to be “more prescriptive”. For instance, it now mandates minimum class sizes of 26. The number of GCSE subjects has been cut to eight.

“It is restrictive,” she says. “In an ideal world we wouldn’t have to. But some classes had just six children… we are sustainable now.”

Fears schools are treated like ‘supermarkets’

Micon Metcalfe, the chief finance officer at the Diocese of Westminster Academy Trust, says said while leaders “may not want to put ourselves in that commercial mindset, it’s discipline about looking at possibilities: tweaking your class size, or the number of classes, teachers with less management responsibilities”.

But Tyler said she’s not sure whether this approach would deter a strong school from joining her trust now and having to give up a “Rolls-Royce” curriculum.

Another trust leader, who uses the model for benchmarking, questions whether it treats schools like “a supermarket”.

Standardised formulas strip heads of autonomy and flexibility, he says, while acknowledging its effectiveness turning around failing schools.

Metcalfe says the direction of travel does pose the question of “what do we want from our public services?” and does this mean government is “saying we’re happy to have less spent on education – and for it to be much more standardised, with less flexibility and innovation?”

However, Miller says it’s not a one-size-fits-all. “But it helps headteachers and timetablers understand the core costs of their timetable.”

Builds in extra curriculum time

Sir David Carter, the former national schools commissioner, says ICFP can become “unhelpful” if it is run too rigidly. “You end up saying that subjects at GCSE with small numbers should be cut.”

But he says the “curriculum bonus” metric in OGAT’s model helps resolve this, building in extra curriculum time.

Once leaders know the non-negotiable costs, Miller says, “you can then have a conversation around added value. That could be smaller class sizes, because that’s right for the school. But it means they can say ‘I’m going to run this, and I understand the costs around it’.”

“When times get tough, you can look at the added-value stuff too for where to step back on.”

While admitting it is a “lean” staffing model, Sir Martyn Oliver, OGAT’s chief executive, says it essentially “helps you make intelligent decisions”.

On concerns over flexibility, he says OGAT is “breaking” its own metrics to allow schools to implement catch-up and deal with high staff illness absences.

But the trust is “doing it on purpose. I’m in control, and if I can’t afford the model, I know where to look.”

It does seem more effective at larger trusts, which Oliver says can give a struggling school more leeway because of the savings made at its more stable schools.

Not as effective for primaries, special schools

Many ICFP advocates agree the model is less effective in primary and special schools.

One leader went further to say it also falls short at mainstream schools with larger number of SEND pupils, as it generally means fewer pastoral staff.

A DfE survey found that 90 per cent of all-secondary MATs used financial curriculum planning, compared with 58 per cent of all-primary MATs.

Of maintained schools or single trusts, 78 per cent of secondaries had used it or planned to in the next year, compared with 52 per cent of primaries.

Feedback from leaders visited by one of the government’s cost-cutters back up concerns about the model not working in special schools.

Sudhi Pathak, the chief operating officer at the Eden Academy Trust of special schools, says this is because the teacher-pupil ratio varies.

One of his schools has one teacher and two teaching assistants (TAs) for a class of ten. Another, for pupils with more profound needs, has one teacher and four TAs for six pupils.

“This makes benchmarking extremely difficult as we are not comparing like with like or consistent environments.”

However, the government is “user testing” a model put together by the Esteem MAT, specifically for SEND and alternative provision schools, to “explore” how it can be improved.

The metrics ‘just won’t hold now’

The Pioneer Academy Trust, which has 14 primary schools, has developed its own primary-specific model, now promoted on the DfE website.

It uses it as a “conversation starter” with heads about their provision, says Lee Mason-Ellis, its chief executive.

Savings have allowed it to invest in a cultural capital programme. Staff are also given extra time off-timetable and schools have access to specialist subject teachers.

But, speaking before government committed to extra school funding, he said pressure meant the metrics “just won’t hold now”.

Energy costs have quadrupled to 8 per cent of budget. Unfunded pay rises have pushed salary costs from between 70 and 72 per cent of expenditure to 76 per cent. One school, always previously in surplus, now has a £47,000 deficit.

The trust is dipping into reserves to underwrite losses this year to limit cuts.

Analysis last week by the Confederation of School Trusts shows more than half of its members could fall into deficit within two years. They include some of the country’s biggest trusts, and those that pioneered the ICFP model.

Delta predicts its energy costs could rise from £1.9 million to £9.6 million.

‘No matter what magic formula, it’s just not going to work’

Even Stephen Morales, the chief executive of the Institute of School Business Leadership that runs the school resource management adviser programme, thinks it’s impossible to balance the books.

“There is variability, but it doesn’t matter how well you’re doing with staff costs. No matter what magic formula we have, it’s just not going to work.”

Leaders are hopeful the additional £2.3 billion school funding per annum will help alleviate these pressures, although there is no news yet on further support with energy costs.

Baroness Barran, the academies minister, said in the Lords last week that the school resource management strategy aimed to help schools “save” another £1 billion.

She claimed £1 billion had already been saved since the scheme launched in 2018, but a funding expert said “cuts” was a more accurate term.

However, Metcalfe says there’s “not going to be much to spare” for those that have been through the ICFP process. “The next savings are in cutting support staff, admin roles – but we need those.

“We can’t take more cuts if we’re also picking up everything that has been cut from elsewhere.”

Management by excel is not the way forward- poor organisational leadership & Management created the huge deficits the article contributors are referencing. It shouldn’t take an overly complicated spreadsheet for school leaders to recognise they haven’t got a ‘balanced’ staffing structure – 5 minutes reviewing the teaching staffing structure or 5 hours aimlessly plugging numbers into a spreadsheet the answer will be the same. Oh well at least it gives these school leaders the air of authority and certainty in the decisions they make – relying on excel is not a substitute for strong effective leadership or is that what these contributors are advocating?!