Schools in the poorest areas are getting better Ofsted grades, but there is still a huge gap with their wealthier counterparts, new analysis suggests.

Experts also point out it is not possible to say how much of the rise is simply because of more ‘good’ grades now being issued – and poorer schools are now actually less likely to get ‘outstanding’.

Chief inspector Amanda Spielman pledged at the start of her tenure that the 2019 inspection framework would “reward schools in challenging circumstances that are raising standards through strong curricula”.

She had said the old framework, which focused more on results, had made it “harder to get a good or outstanding grade if your test scores are low” as a result of a “challenging or deprived intake”.

As Spielman nears her final month in office, Schools Week looks at whether she’s followed through on that promise…

‘Tentative signs’ of change…

In a December 2019 blog, Ofsted admitted schools with more deprived intakes were less likely to be rated ‘good’ – despite the inspection changes.

But has it changed since? Schools Week replicated the analysis, which compared grades issued to schools broken down by their income deprivation affecting children index (IDACI) quintile.

In 2018-19, there was a 17 percentage point difference between the proportion of the most and least deprived schools deemed ‘good’. But last year, the gap was just four percentage points.

But IDACI is based on the postcode in which children live, which might not necessarily reflect their disadvantage levels.

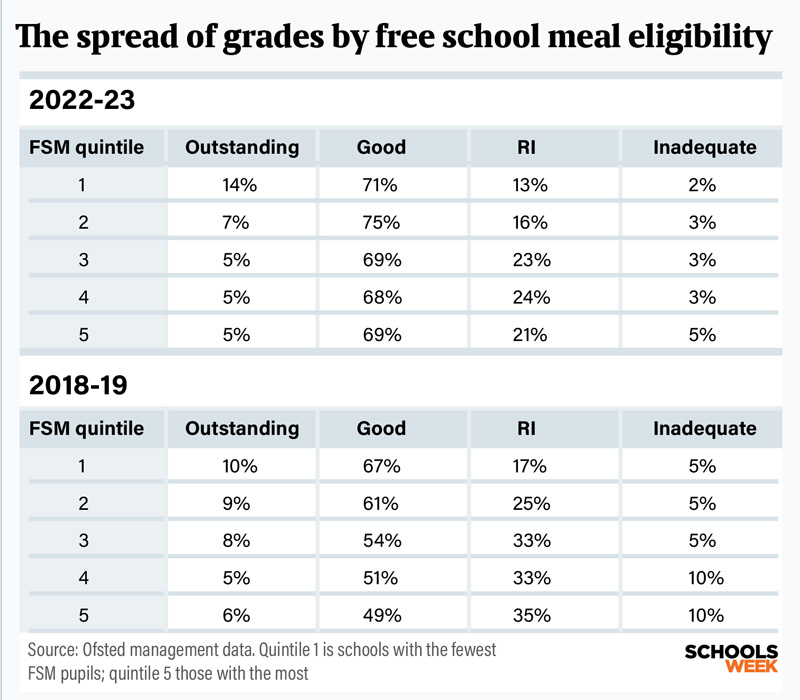

However, analysis of Ofsted grades versus the percentage of pupils known to be eligible for free school meals also shows a similar trend.

John Jerrim, professor of education and social statistics at UCL’s Institute of Education, said the analysis showed “tentative signs that the link between Ofsted judgments and disadvantage may be weakening”.

…but all grades are improving

But he urged caution on drawing any firm conclusions.

One complication is that ‘outstanding’ schools have only recently started being inspected again – meaning the cohort of schools visited by inspectors last year is different to 2018-19.

In autumn 2021, when inspections resumed post-Covid, Spielman said halving the number of outstanding schools to one in ten was a “more realistic starting point for the system”.

However, when we re-ran the analysis with previously ‘outstanding’ schools omitted, the gap between schools with poorer and wealthier pupils still shrank.

Dave Thomson, the chief statistician at FFT Education Datalab, said this supported the finding that schools in poorer areas were getting better grades.

But another issue is the different profile of grades handed out under the current framework compared with pre-2019.

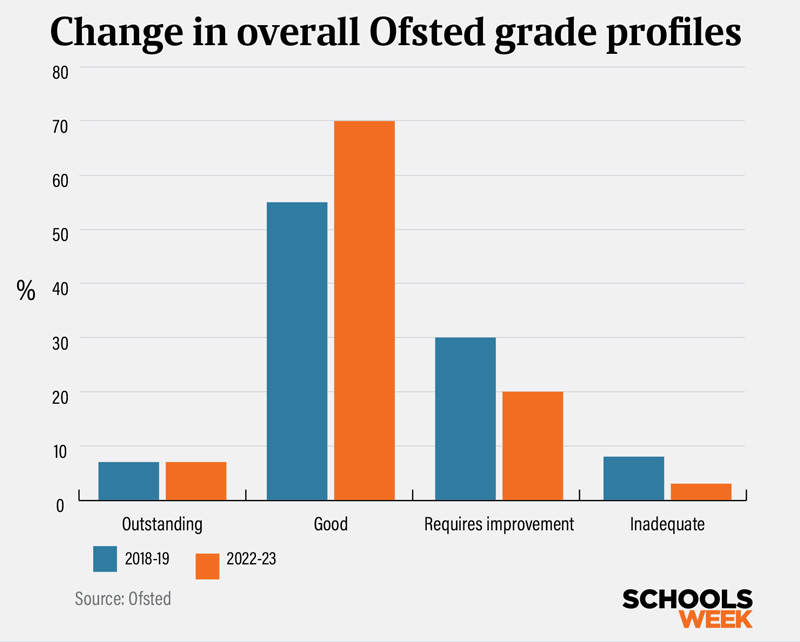

For instance, across all inspections in 2018-19, just 55 per cent of schools were rated ‘good’ and 38 per cent were below ‘good’.

But last year, 70 per cent of schools were rated ‘good’ and just 23 per cent were less than ‘good’.

Thomson said this meant we won’t know if “the schools that were judged ‘requires improvement’ or ‘inadequate’ in the past would have fared any better had they been inspected under the current framework.

“In other words, has the standard Ofsted expects changed?”

And ‘outstanding’ gap gets bigger

But while more ‘good’ grades are given out, far fewer ‘outstanding’ grades are now awarded.

This has resulted in a growing gap in the top grade between schools with the poorest and wealthiest pupils.

Our analysis shows 14 per cent of the schools with the least free school meal pupils got ‘outstanding’ last year, compared with 5 per cent of those with the most.

This is a much wider gap than in 2018-19 (10 per cent versus 6 per cent respectively).

Jerrim said this finding was “worrying”. When broken down by phases, the change at primary is minimal.

But at secondary level, the gap has ballooned. In 2018-19, just 2 per cent of secondaries with the poorest pupils got ‘outstanding’, compared with 17 per cent with the fewest.

Last year, this had changed to 5 per cent and 36 per cent, respectively.

What does it mean for deprived schools?

Paul Tarn, the chief executive at Delta Academies Trust, suggested that “middle-class cohort[s]” were still “much better placed” to gain the top grades because they were “better able to articulate their learning” to inspectors.

Tom Campbell, the chief executive of E-ACT, said he was concerned inspectors were still failing to “understand the impact a school is making despite the challenges”, which included acute recruitment issues.

Chris Zarraga, the director of Schools North East, said most leaders in the region thought the framework was “an improvement”.

“However, the persistence of the gap is a reminder that the impact of long-term deprivation, which the north east has higher rates of, is not adequately being taken into account.”

In response to our analysis, an Ofsted spokesperson said it “always” took a “school’s circumstances into account on inspection, including its deprivation level”.

“In 2019, our new education inspection framework put greater emphasis on the substance of education – the curriculum.

“Many schools are now more focused on providing their pupils with a broad and rich curriculum, and this is reflected in recent positive inspection outcomes.”

Keegan’s Ofsted grade boast is ‘cynical’, says academic

Gillian Keegan’s claim that a rise in Ofsted grades since 2010 shows the Conservatives are “relentlessly driving up standards” is “a complete red-herring”, says a London academic.

As of August 31, 89 per cent of schools were rated ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’, a one percentage increase on the year before.

On social media, Keegan highlighted that “only” 68 per cent of schools were rated ‘good’ or better under Labour in 2010, when the Conservatives came to power.

“This progress is thanks to the dedication of our hard-working teachers and the reforms that we have introduced since 2010 that have made a lasting impact on the quality of education received by young people,” a spokesperson said.

But John Jerrim, professor of education and social statistics at UCL’s Institute of Education, described the education secretary’s claim as “a complete red-herring and pretty cynical”.

Schools rated as ‘outstanding’ were exempt from inspection for eight years until 2020, meaning the proportion of top-rated schools “couldn’t decline – it could only stay still or go up”, he said.

Four in five previously ‘outstanding’ schools have lost their top grade in the past two years.

The introduction of ungraded inspections for ‘good’ and ‘outstanding’ schools in 2015 had “made it quite hard for a school rated as good to be downgraded”, Jerrim said.

“Hence, again, this has driven the [percentage of] good and outstanding to increase.”

Ofsted data up to August shows that 2 per cent of ungraded inspections of ‘good’ schools end up being converted into graded inspections, where the outcome may change.

The proportion of ‘good’ schools in Ofsted’s analysis has risen from 66 per cent in August 2019 to 73 per cent last year.

Your thoughts