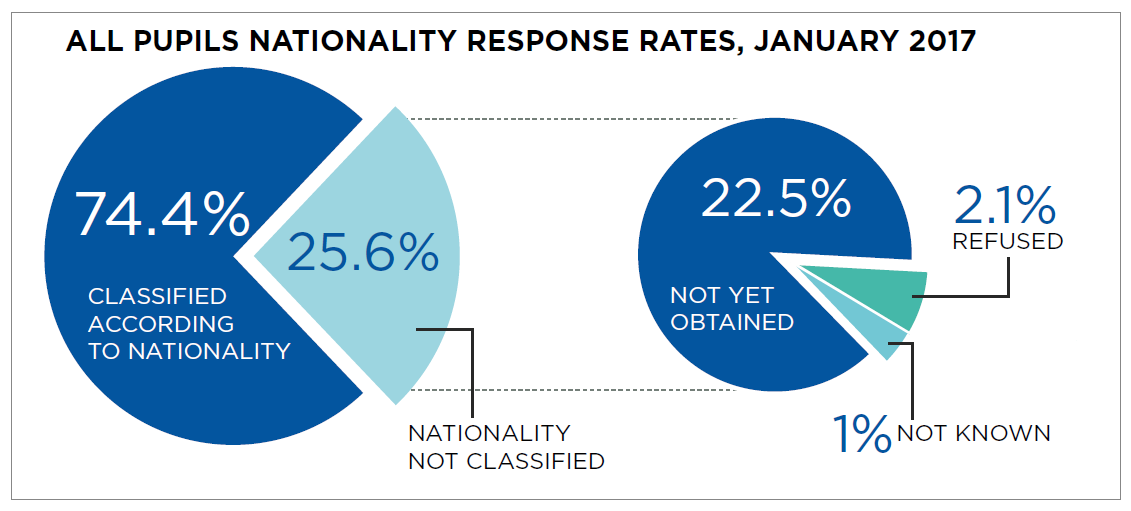

Schools failed to obtain nationality data for a quarter of their pupils this year, indicating a significant resistance to the controversial new requirement to collect it from school staff, parents and pupils.

New government data shows the information was successfully collected from around three quarters of the 8.1 million pupils who were registered in January.

But data for 22.5 per cent of pupils – around 1.8 million children – was “not obtained” – meaning it had not been collected by schools when the forms were submitted. In 2.1 per cent of cases, parents or pupils pointedly refused to provide the data.

The release is based on data taken during the spring census in January, and shows that the government now holds nationality data on more than six million pupils, and birth country data for almost 6.2 million.

Schools have a duty to ask parents and pupils for the data, but they are allowed to refuse to provide it.

Where data is listed as “not yet obtained”, it could be either because the school refused to or failed to collect the data. Country-of-birth data is yet to be collected for 20.6 per cent of pupils. However, these figures decreased between the autumn and spring census, and Schools Week understands the government expects them to decrease further as schools become more used to the collection.

Campaigners last year asked schools and parents to resist the controversial data collection, which began last October after legislation was rushed through parliament during the summer recess.

Even though it initially claimed the scheme had nothing to do with monitoring immigrants, the Department for Education was forced to admit it had planned to share the data with the Home Office for immigration control purposes. It subsequently dropped this aim amid the backlash.

The response-rate data was released on the same day that campaigners seeking to halt schools from collecting it requested a judicial review of the policy in the High Court.

The campaign group Against Borders for Children, represented by the human rights charity Liberty, will focus its legal argument on whether the policy infringes the rights of pupils. The groups also argue the policy serves no “educational purpose”.

The change to the school census sparked a huge backlash from parents after some schools overreacted to their new duty, demanding copies of pupils’ birth certificates and passports.

In one notorious instance, only non-white pupils were chased for their data, while in other cases, parents were told they had a legal duty to provide the information, when no such requirement exists. Vague government guidance, which was recently criticised by the Information Commissioner’s Office, has been blamed.

Against Borders for Children launched a crowdfunding campaign for its legal bid last month, and has so far raised £4,000.

Lara ten Caten, a lawyer for Liberty, said the process was “toxic” and turned “sanctuaries of learning and development into places of fear”.

“The government cannot even explain why it needs to know children’s nationality and country of birth in order to educate them,” she said.

Your thoughts