Suicidal children are being turned away from overstretched Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) with schools instead told to “keep them safe”.

Many mental health services are also refusing to see children with a diagnosis of autism and other neurodevelopmental differences on the grounds they do not meet the criteria for therapy, Schools Week can reveal.

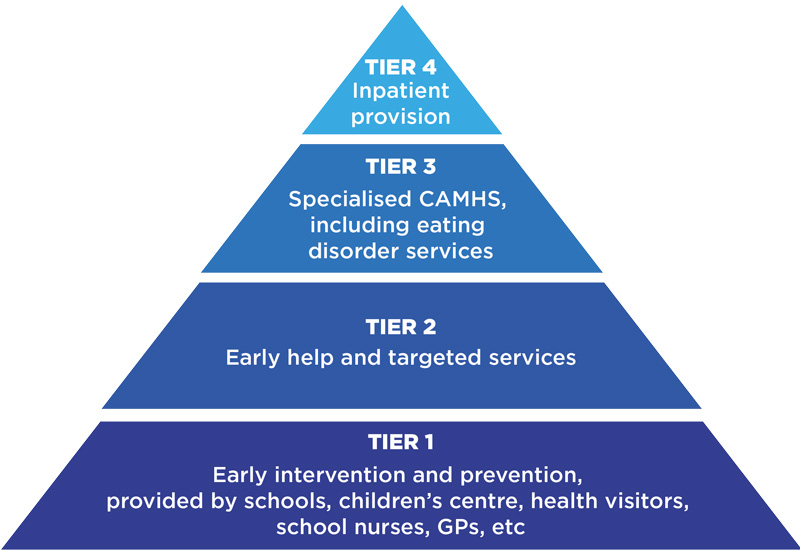

Instead, families say they are left to “keep children alive” as they either wait or are rejected from tier 3 and 4 CAMHS (see diagram below). This leaves schools being left to “plug the gap”.

Suicidal children rejected

One mother in Warwickshire says that her 13-year-old daughter had made four attempts to kill herself in 2018, but CAMHS told the family there was a “two-year wait” for an assessment.

“My husband was sleeping in front of the front door at night, because she’d said she was going to run out in front of a car in the middle of the night,” she says.

Instead, her daughter ended up in A&E five times after suicide attempts. The ward was “half full of teenage girls waiting for CAMHS”, says the mother.

Even when a child repeatedly tries to kill themselves – we’re told to just ‘keep them safe’

Meanwhile Emily, a mother in the Midlands, says her daughter was referred to CAMHS by a paediatrician in January 2016, but was only seen in August 2017.

However, when CAMHS assessed her daughter, they felt her suicidal feelings “were to do with her autism” and no therapy was offered. In the same week CAMHS wrote to say they intended to discharge her daughter, the girl was taken to A&E for self-harm, says Emily.

“Then they had to keep her on after that, because of the [A&E] admission.”

Schools told to ‘keep kids safe’

Schools corroborate parent stories, reporting that CAMHS thresholds are too high.

Kent Catholic Schools Partnership said CAMHS referrals “are frequently rejected […] even for some pupils who have attempted to take their own lives”.

Academy Transformation Trust said “if the child is not in crisis at that exact moment but has told us that they want to kill themselves – and tries repeatedly even when in school – […] the school is told to ‘keep them safe’.”

Caroline Barlow, headteacher at Heathfield Community School in East Sussex, adds schools are expected to “plug that gap but we do not have the expertise at a CAMHS level to be able to do that.”

Our FOI request found of 17 NHS trusts who provided data, on average 18 per cent of CAMHS referrals have been rejected or deemed inappropriate so far since April, up from 17 per cent last year.

At Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust, rejections since April sit at 32 per cent, up from 28 per cent in 2018-19. A spokesperson said they review and signpost parents to services.

The number of referrals to CAMHS last year was 50 per cent higher than in 2020 (409,347 referrals), analysis by the Royal College of Psychiatrists also shows.

CAMHS adds hurdles to access support

To filter referrals, CAMHS are placing extra non-statutory requirements on schools and parents, academy trusts have warned.

An educational psychologist assessment must be completed before CAMHS will see a child, according to the Creative Education Trust. Similarly, Anglian Learning Trust says parents must do “a parenting course before their application is accepted”.

Another common reason for a pupil being rejected for therapy is having a diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental difference. Five out of 12 families Schools Week spoke to had experienced this issue, even if their child self-harmed, was suicidal or had an eating disorder.

One mother in Cheshire, whose 7-year-old daughter is diagnosed with autism, ADHD, and anxiety disorder, was rejected from CAMHS three times in 2019 and 2020 even though her daughter was harming herself.

Only when the mum paid £500 for a private psychiatrist who had previously worked in CAMHS did the referral go through “within weeks”.

Tasha, a parent with a 12-year-old son in Warwickshire, said: “As soon as you have that diagnosis of autism, they say it’s all part of his autism. No it isn’t, not all autistic people are like this.”

A booklet from the Coventry & Warwickshire Partnership NHS Trust lists its ‘exclusionary criteria’ for the home mental health support team, saying it is “less likely to offer a service for the following conditions […] patients with mental illness secondary to physical, organic or neurological conditions”.

The Community Academies Trust told Schools Week its CAMHS was “only offering a diagnostic service for ASD and ADHD at the moment, which is hard for families”.

Rejections putting more children in hospital

Emily and her husband have had to fight two tribunals in 2020 and 2021 against the local authority, eventually getting a special educational needs school placement for their daughter this year.

But Emily says the delay over six years means “the damage has been done”, and her daughter was back in A&E before Christmas after a self-harm incident.

Jon Goldin, a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, said this can end up with children instead being sent to tier 4 inpatient wards later down the line.

This can be “disturbing” for children to witness others unwell, adding there is also a “lack of capacity. It’s often very hard to get a bed.”

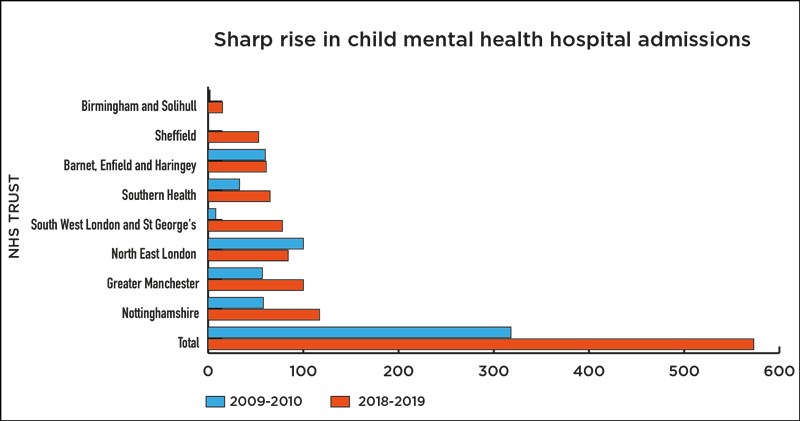

Eleven of 12 NHS trusts that answered our FOI saw inpatient admissions increased between 2009 and 2019 – before Covid hit.

South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust had 70 more children.

Meanwhile, of the nine trusts with data, eight saw an increase in admissions for 10 to 15-year-olds.

But this rise tailed off after Covid hit, although this could be because pupils are falling through the cracks with fewer referrals – as schools were closed – and the pandemic further stretching services.

For instance, NHS data shows that one in six children now have a probable mental health condition in 2021, up from one in nine in 2017.

Data collected by the children’s commissioner office also shows over a third of children accepted onto waiting lists in 2020-21 are still waiting for treatment to begin.

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said it is “expanding and transforming NHS services backed by an extra £2.3 billion per year by 2024, to allow hundreds of thousands more children to access support”.

A Department for Education spokesperson said the government has “made an unprecedented investment in mental health services, both through the NHS and tailored support available in schools”.

Schools Week spoke to 12 families whose children suffered from self-harm, suicidal feelings or eating disorders after contacting groups such as Not Fine in School, Square Peg and Autistic Girls Network. To protect their anonymity we have not included full names as requested by parents.

Samaritans are available 365 days a year. You can reach them on free call number 116 123, email them at jo@samaritans.org or visit www.samaritans.org to find your nearest branch.

Your thoughts