Schools are swapping English and maths for lessons in wellbeing, running interventions akin to those used for drug addicts and setting up “zen dens” to tackle pupils’ worsening mental health and get them back into schools.

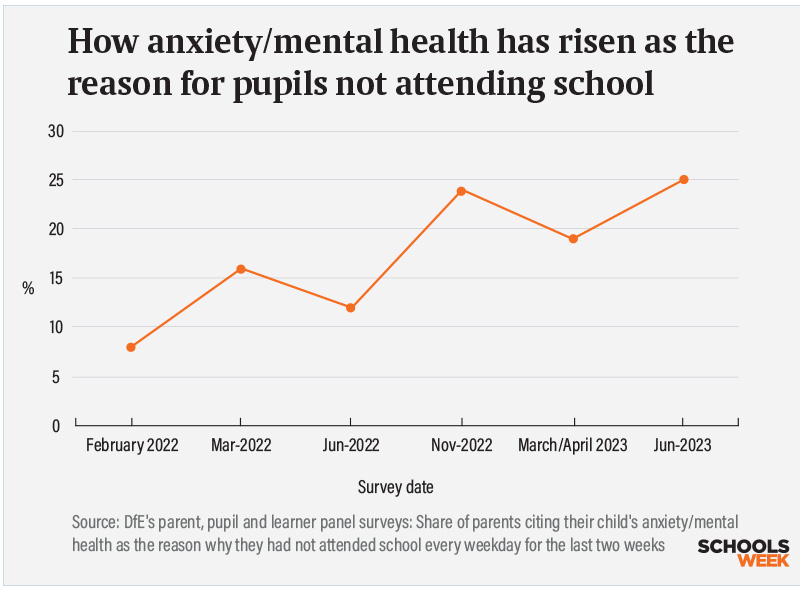

One in four parents cited anxiety or mental health problems as a reason why their child was absent from school, according to a Department for Education parent and pupil panel survey undertaken in June. This is up from just 8 per cent in February 2022.

Heads told Schools Week that the cost-of-living crisis, social media bullying, family breakdown, the Covid legacy and climate change fears were all causing more of their pupils to express feelings of anxiety.

With long waiting lists for mental health services, and only around a third of schools covered by the government’s mental health support teams, Schools Week has looked at the way schools are stepping up to meet the challenge.

Signing attendance contracts

Mahatma Gandhi and his non-violent resistance movement provided the unlikely inspiration for Oasis Community Learning’s new approach to non-attendance. Jon Needham, director of safeguarding for the 54-school trust, says it sets up “family interventions” in the style of those intended for drug and alcohol addicts.

“Parents tell their young person, ‘I love you, but I’m not going to tolerate this anymore’,” he says. “Kids sign contracts” for a 10-week programme committing to improve attendance and behaviour.

“It’s a massive opportunity to change these family’s lives,” adds Needham. “If we can support parents to be more in control – for parents to parent rather than try to be their kids’ best friend – then you get structure. A kid with structure is more likely to cope, and then more likely to attend.”

The programme also brings parents together in WhatsApp communities to support each other, after the trust found “lonely parents who didn’t realise that [many others were] struggling with the same thing”.

Providing support to families, as well as their pupils, is a common theme.

The London South East Academies Trust, which has nine schools mostly for pupils with social, emotional and mental health difficulties (SEMH) needs, has family liaison officers who visit them at home to understand the barriers to their attendance.

Sometimes their tasks include driving pupils into school, adds deputy chief executive Neil Miller. “Ultimately, whatever it takes.”

Creating calming spaces

But, as more pupils are displaying heightened educational needs, schools are under pressure to become more inclusive – rather than relying on costly external provision.

Many are establishing separate spaces outside of the classroom for pupils to learn, or simply escape to feel less anxious, sometimes called a nurture hub, SEMH zone or “zen den”.

Anna Smee, managing director of Thrive, which helps schools to develop strategies for pupil wellbeing, says it is something that all schools can offer.

“It could involve a large outdoor area with a focus on nature, a quiet corner in a classroom with something soft to sit on and books, or mindfulness activities on hand to promote relaxation,” she adds.

Last summer, Honiton Primary School in Devon built a 40-foot timber and canvas yurt for its SEMH support. It includes a canteen kitchen and fire pit. Headteacher Christopher Tribble describes it as “a breakout space for peace and calm, assemblies and storytelling” in the “lovely forest” grounds.

He says the yurt was inspired by “the success we had using the outdoors style of life to get through Covid”, when “being in our woods and in tents really helped the staff and children”.

Sometimes it can just be the little things. Heartwood CE VC Primary and Nursery School, in Norfolk, uses soft and natural lighting where possible.

Many of its displays use neutral colours rather than the “garish” ones previously on display, said the school’s Thrive lead, higher level teaching assistant Sophie Watson.

The school tries to embed a sense of belonging. There is a wooden dolls house in a corridor, in which all pupils have made wooden peg dolls of themselves. “They can see themselves in there and know that they are part of the Heartwood family.”

In his latest book, leading education policy thinker Doug Lemov writes: “It is possible to combat the effects of the pandemic, the epidemic [of rising screen time and social media] and the rising tide of mistrust that our students are facing, and to help them feel and sense of belonging in their school.”

Pupils as mental health champions

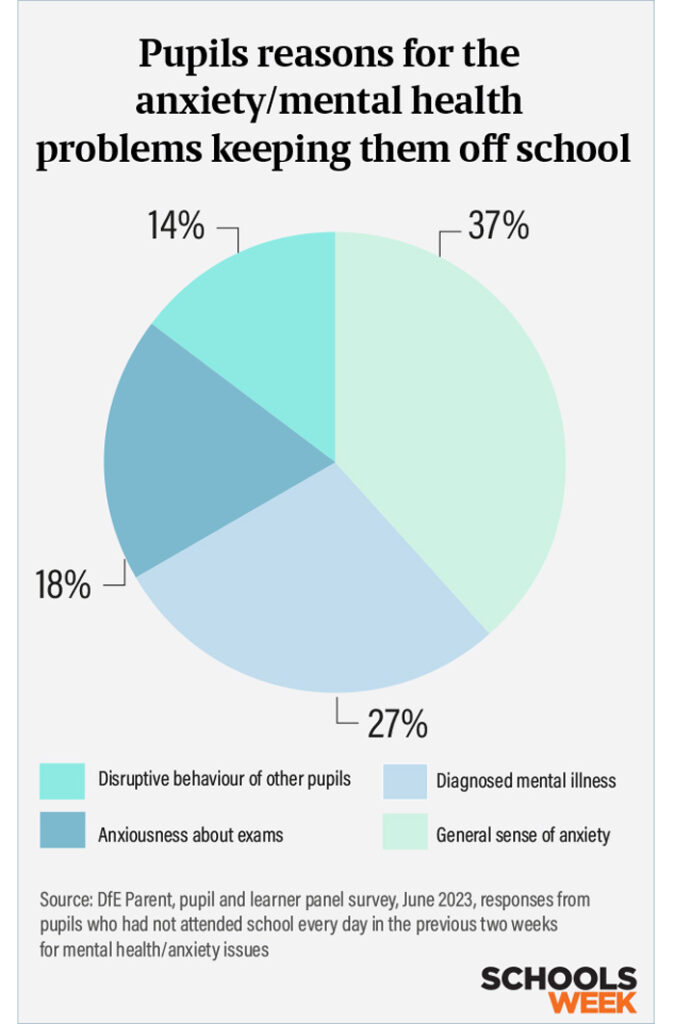

Three out of five parents of children who missed school because of a mental health issue said the problem was a “general feeling of anxiety or anxiousness not specifically attached to any one thing”. Schools and councils are surveying their pupils to understand what the issues are, before seeking a solution.

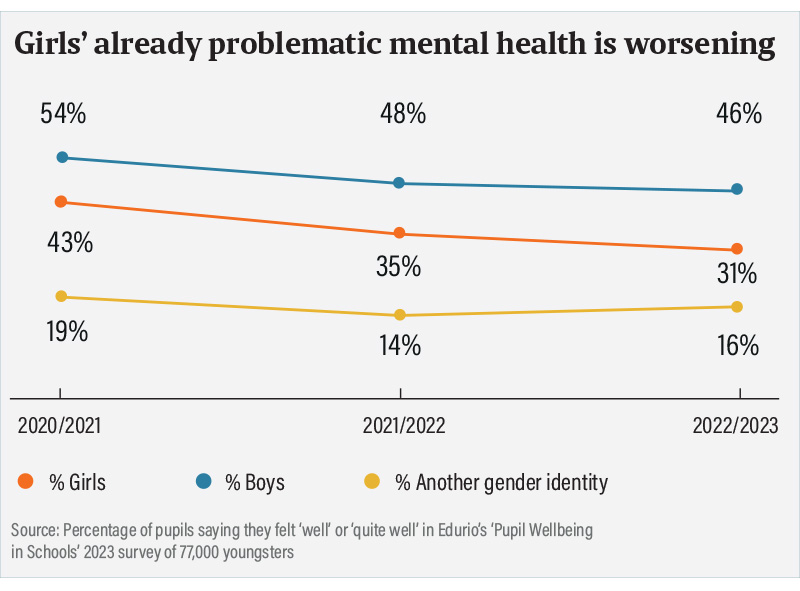

A survey of almost 13,000 year 11 pupils by UCL and the Sutton Trust last year found more than half of teenage girls are suffering from poor mental health. Almost a quarter said they had self-harmed in the past year while one in 10 said they had attempted suicide.

A survey of more than 70,000 pupils by Edurio found the problem is getting worse. The proportion of girls saying they felt “well” fell from 43 per cent in 2020-21 to 31 per cent last year. Scores for boys fell from 54 per cent to 46 per cent over the same period.

Camden has put on workshops in body image and self-esteem in response to surveys of pupils showing this was a growing issue in the borough. It also trained 133 pupils from 10 schools to become wellbeing champions, supporting peers with poor mental health.

A survey of parents, students and staff by academy trust E-Act found youngsters were “feeling isolated and alienated” due to “fractured families”, according to regional executive headteacher for the West Midlands Michelle Scott. This was “compounded by a lack of aspirations, because they can’t see a way out”.

Every school must now sign up at least two staff for whole-trust training in mental health throughout the year. But Scott says it is “a little easier” to find support in big cities like Birmingham, where many of its schools are based and more specialist groups are available.

The trust worked with one group focused on “toxic masculinity”, which helped pupils considered to be potential targets for gangs. It was “supporting anxieties in the context that these pupils live in” which was “really powerful for those kids. But those groups don’t exist everywhere, and the quality is very varied,” says Scott.

Early findings from a government study indicate a “causal link between mental health problems and absence” from school, according to minutes from the October meeting of the national Attendance Action Alliance.

Russell Viner, the Department for Education’s chief scientific advisor who is leading the study, says a “calm, safe and supportive school environment is important for increasing confidence and attendance”.

More specialist boots on the ground

Government-funded mental health support teams, launched in 2018, have reached only a third of pupils while just 58 per cent of schools have staff who have undergone the senior mental health lead training, promised to all schools by 2025.

But almost half of the mental health leads say they lack time to provide the required support on top of their day jobs. Where budgets stretch, schools and trusts are hiring their own specialists.

Oasis is spending £1 million a year on employing 13 mental health workers. Needham says the team is “improving the quality of referrals to CAMHS services, because young people have already started therapy while they wait for their assessment.

“A lot of stuff – anxiety, bereavement, self-harm – is no longer being addressed by CAMHS services. Somebody’s got to do it, so we’re doing it.”

Similarly, the Harris Federation of 55 schools in and around London has its own central mental health team of four councillors and a senior practitioner. But, because “everybody wants people trained in mental health work … finding specialists was really difficult”, says chief executive Dan Moynihan.

That fact is reflected in the number of roles on the jobs site Indeed relating to children’s mental health in the UK, which jumped by 72 per cent from September 2021 to 2023.

While larger trusts may find cash to fund such teams, many others cannot. A survey of more than 1,000 school staff last year found fewer than a quarter had been able to access regular specialist mental health support for pupils.

Brookvale Groby Learning Campus, in Leicestershire, trained staff to become emotional literacy support assistants – using part of its recovery premium funding to employ a mindfulness coach. The coach works on wellbeing with pupils and staff who are feeling anxious and the initiative has received positive feedback.

Swapping maths for wellbeing lessons

While personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) studies have always involved educating pupils about mental health, some schools are putting the issue front and centre.

Kensington Primary School designed a new curriculum which headteacher Ben Levinson says “goes much broader and deeper in teaching children to understand their emotions, and strategies to deal with them”.

That has meant teaching fewer hours of English and maths (which normally takes up 60 to 70 per cent of primary timetables) to allow more time for wellbeing lessons.

Kensington’s pupils also wear trainers and tracksuits throughout the day so they can take part in “active learning breaks”. The sporty uniform also reduces the time taken to get changed after PE lessons – the focus of which is “much more about being physically fit than learning to play hockey or tennis”.

“There’s no point in children getting great academic qualifications if ultimately they’re destined to drop out because they mentally cannot cope,” says Levinson, who is also chair of the WellSchools network of almost 2,000 schools.

“When we look at children who find learning challenging, so often it’s a mental health problem driven by anxiety and lack of confidence.”

Claire Garnett, head of Juniper Hill Primary School in Buckinghamshire, was moved to write a life skills curriculum after seeing a year six pupil “lose a third of her body weight” with anxiety. Pupils now get weekly lessons in life skills using 12 themes, exploring “the opportunities of adversity”.

Garett says the school, which has a play therapist and plans to open an SEMH hub next year, tries to “create a culture in which it’s OK to have a wobble”.

She says” “Adversity is going to happen, so we try to reframe it to make things positive. We’ve got to normalise some of the stuff that’s making people anxious, because this is life.”

Finally we find there are leaders, heads, teachers, support staff starting from where the children and young people are in their lives. The idea of trying to ram a square peg into a round hole deserves to be discarded entirely. The professionals named in this article deserve so much support. I just hope the Labour Party Shadow Education Minister sees the utter logic of the approach of these ‘pioneers’ and consequently invests substantially in such programmes in order that they can be rolled out across the country. It’s a powerful way to address and evidently arrest the terrible impact that 13 years of Gove’s influence on the educational environment, together with the deprivations of austerity, general social pressures, the power of social media’s aggressive and cynical exploitation and manipulation of young people. The negative attitude of the Tory Party, especially the Department of Education, towards children and young people has been one of the major scandals of the last 14 years.