There are moments as Nick Brook talks about narrowing the opportunity gap for disadvantaged youngsters when he becomes so animated it’s as though he’s delivering a rousing speech to union delegates.

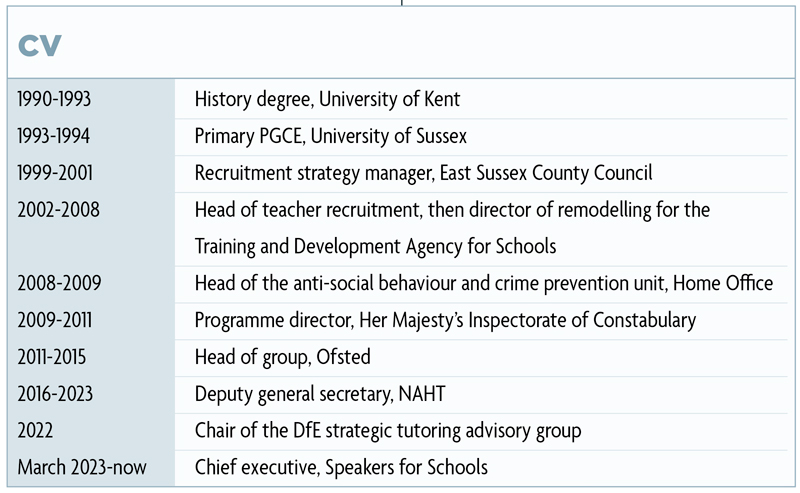

This infectious passion served him well as deputy general secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT) – a role he held for seven years before joining the social mobility charity Speakers for Schools as its chief executive in March.

But it was not a quality his bosses appreciated during his ten years in the civil service.

After two hours of psychometric tests for the Home Office, Brook was told the results were “broadly in line” with expectations of a senior civil servant. However he “appeared to seek excitement” more than they would expect.

“I should have seen the warning signs,” he says.

Gaining ‘real power’

Brook believes his ability to “do good and influence” was “so much greater” at the NAHT than while leading the Home Office’s anti-social behaviour and crime prevention unit or as programme director of Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary a few years later.

His union job gave him a “seat at every table” and “real power” to his words, which wasn’t the case then. “There was so little scope to actually move things in a positive direction. You’re always at the whim of the minister.”

He says the union is “interested in finding solutions to problems rather than just shout at walls”, as opposed to others who are “all about the soundbite”.

“Then they think themselves successful because they’ve got the column inches the next day.” (When asked which unions, he says it’s not a criticism of any in particular, more a reflection on “how easy it is to poke holes rather than try fix them”.)

Brook’s civil service experience gave him an appreciation of the hard work that goes into shaping policy. It was “better to be close” to those in government, “assuming you’re on the same side and then able to take the edges off bad policy, than on the outside shouting at them. You know you’ve lost when it starts turning into a slanging match.”

He pushed the government hard on its response to reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete after picking up concerns about the true scale of the problem late last year.

The fear inside government was “not necessarily the concrete falling on your head”, but that any collapse could “release a plume of asbestos fumes…so if the concrete doesn’t kill you, the asbestos will get you”.

He raised the issue with MPs at the time, but was confused at the lack of interest.

“Everyone just wanted to talk about ‘is this enough money to see off strike action’? They completely underestimated the significance.”

Speaking at schools

During his 20 years of leadership positions in education, Brook has got used to being “the only one in the room” who didn’t attend a private school or Russell Group university.

Levelling the playing field is a key reason he joined Speakers for Schools. Founded in 2010 by journalist Robert Peston, the charity gets leaders from sectors such as business, politics and the arts to deliver inspirational talks in state schools.

It now has 1,600 speakers and 120 staff, with a remit that’s expanded more recently into finding work experience for pupils at the 2,300 secondary schools and colleges it works with.

Funding comes primarily from the Law Family Charitable Foundation, run by hedge fund manager Andrew Law, and is topped up through donations.

Peston’s journalistic connections have helped bag speakers that include politicians David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband, Dragons’ Den business guru Deborah Meaden and chef Tom Kerridge.

When Microsoft founder Bill Gates visited a school in a deprived part of London, some parents were “in tears because they said ‘people like that don’t come to places like this’. His visit showed them, ‘you do matter’,” says Brook.

Student pretence

Brook can resonate with the experiences of the disadvantaged pupils he talks to. He attended an “awful” Coventry comprehensive where “despondency hung in the air”.

He was the only pupil in his year – and the first in his family – to go to university.

He puts academic success down to regularly taking two buses to the University of Warwick and “hiding out in the library reading books, pretending to be a student”.

After completing a PGCE at the University of Sussex, he became a primary teacher in Eastbourne.

Although he loved teaching, he was seconded to become a council teacher recruitment manager and never returned to the classroom. He “failed abysmally” in his initial recruitment remit – encouraging more men into primary teaching – but later set up a successful teacher training programme in Hastings.

In 2002 he moved to The Training and Development Agency for Schools, a now defunct teacher training quango, where he led on teacher recruitment with sentimental TV campaigns such as “No one forgets a good teacher”.

After stints at the Home Office and police inspectorate, Brook returned to education in 2011 with Ofsted, leading on thematic and subject inspections under Sir Michael Wilshaw.

The plan was for “visits from a local HMI who would know their schools, have a cup of tea with the head and walk around. Any HMI worth their salt could very quickly determine if they should call in their team for a proper inspection”.

But Wilshaw was “very rapidly told” that “an inspectorate…needs to go in and inspect’”.

They ended up rolling out “short inspections”, which “didn’t lower the stakes anything like it should. One of the most frustrating things about Michael Wilshaw is that a lot of the time, his instincts were great.”

Reaching for the stars

Brook has been critical of Ofsted since. Just last month he wrote for Schools Week about how the inspectorate needed to get its house in order.

Careers education in schools also needs a fix, which is why Speakers for Schools has “reorientated” itself in the past five years to meet an ambition that by 2028 every youngster in state education will get access to high-quality work experience.

Brook says school career leads “lack capacity”, while employers are beset by competing work placement requests for T-level students and apprentices.

He wants pupils to reach for the stars, a nod to his own quirky side story of being an acting extra – something he plans to return to after he retires.

After challenging himself to appear in a film (he has “no acting skills whatsoever”), he nabbed a role as a tie fighter in Solo: A Star Wars Story. It was a “blink and you’d miss it” scene, but scooped dad-kudos because a Lego model was made of his character.

‘We’ve got a race on our hands’

Brook is also passionate about improving tutoring. He now leads the government’s tutoring advisory group to ensure the National Tutoring Programme has a lasting legacy in schools.

He says the government is “obsessive” about delivering its promise of six million tutoring programmes, but with “no conversation whatsoever about the impact. It was at risk of hitting its target, but missing the point.”

With a year of the programme left and almost four million programmes delivered, “we are none the wiser” on what makes good tutoring.

“We’ve got a race on our hands to get as much learning out of it now as possible.”

If tutoring can narrow the attainment gap and work experience the opportunity gap – then Brook believes more youngsters will be able to climb the social ladder, as he did.

“It was not lack of talent in my school year that meant I was the only one who went to university. It was lack of opportunity.”

Your thoughts