Excluded children in a third of areas are stuck on waiting lists for specialist provision, as exclusions appear to be rising faster than councils can keep up with, our Schools Week investigation shows.

Pupil referral units have expanded official capacity to keep up with demand in two in five councils – 25 places on average each, freedom of information request responses from 98 councils show.

But over a third of councils still had waiting lists this summer for PRU places, with an average of 20 children on each list, some receiving no education at all or just online tutoring.

Leaders say an increase in exclusions is leaving their PRU overstretched and unable to provide the tailored support needed to meet the needs of their pupils. A sample of council responses appears to back this up.

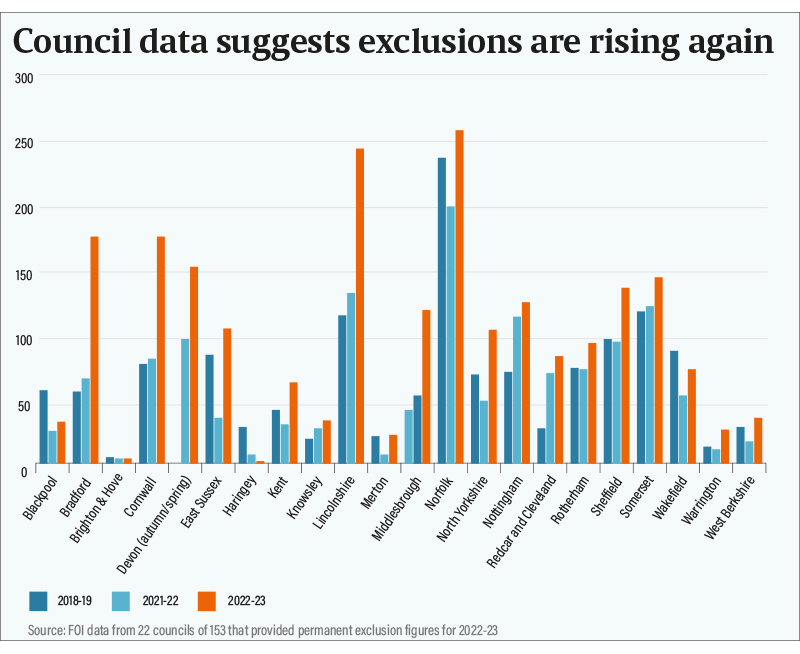

The 22 councils that provided exclusion data for last year saw rises of 61 per cent following a pandemic lull.

Sarah Johnson, president of PrusAp, a body representing that sector, says there needs to be swift action to prevent a crisis.

“While some local authorities have taken steps to increase capacity, the reliance on online provision … is still a pressing issue.”

Lack of capacity to meet demand

Leaders say their success in turning excluded children’s lives around is down to smaller classes and the ability to provide more tailored support.

National figures show 13,191 pupils in PRUS last year, up 13 per cent from 11,684 in 2021-22. This works out as an average 39 pupils per unit this year, compared with 35 the year before.

However, this is still below pre-pandemic 2019-20, when there were just over 15,000 in PRUs – an average of 44 pupils in each unit.

But some PRUs have converted into alternative provision academies in the past decade, which could impact the figures.

We asked all 153 councils for data relating to PRU capacity last year. Of the two in five who increased provision beyond official capacity numbers, Sandwell had the largest rise of 80 places. Its PRU had 66 pupils at the last census..

Fifty-nine pupils also went to alternative provision outside the local authority area.

The lack of available provision is also evident in schools’ use of Code E, indicating when a pupil has been excluded but no alternative provision made for them.

According to data provided by school management information provider Arbor from its 5,471 schools, the use of Code E in secondaries rose from 0.11 per cent in 2022 to 0.15 per cent in 2023.

Where capacity is not increased, Steve Howell, PrusAp’s representative for school participation, says others are “just expected to shoehorn kids in or they’re putting them on waiting lists for provision, and giving them a limited offer of online tutoring in the meantime”.

Pupils on waiting lists

Councils have legal duties to arrange suitable full-time education for permanently excluded pupils within six days of their exclusion. But current pressures hinder this.

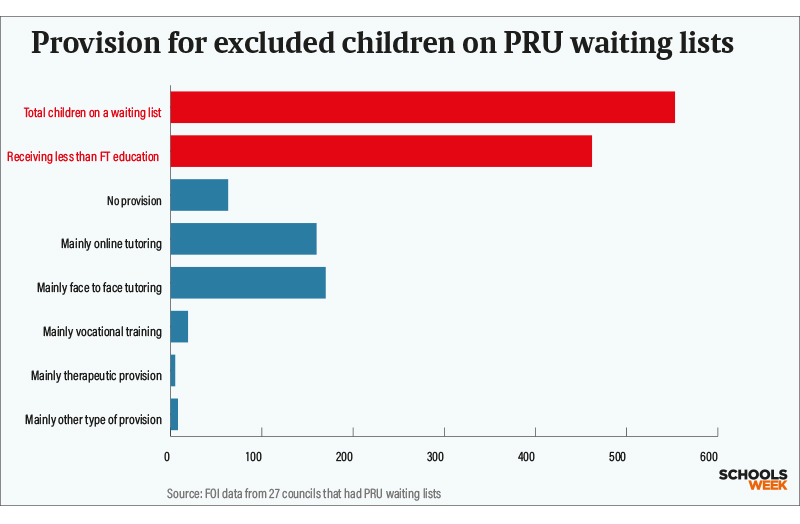

Our FOI found 27 councils had 553 pupils in total on waiting lists. However just 78 councils were able to respond, meaning extrapolated nationally the real figure could be double.

There were just under 7,500 pupils in PRUs last year.

Nine in ten (92 per cent) on waiting lists were receiving less than full-time education, while 12 per cent of councils admit that some children (63 in total) have been left with no provision at all.

In almost one in ten areas, children have been offered mainly online tutoring.

Lincolnshire, which no longer has a PRU, went out to the market “multiple times” to find provision for its 80 children currently without placements.

But providers were “unable to offer further capacity in or around” the county, says Martin Smith, its assistant director for education.

The council has commissioned online home tutoring for these children as an “interim arrangement”.

‘They’re just sat at home’

The Archway Academy PRU in Redcar and Cleveland reached capacity by February in the 2021-22 school year, with 69 permanent exclusions. It established home tuition with weekly council home visits.

Blackpool’s PRU, Educational Diversity had 140 pupils on roll in May, but places for only 110. And Essex in May required an extra 82 places.

Some children in Essex are understood to have waited for up to a year for educational provision after being excluded, and even now they are only receiving 15 hours a week of home tuition.

The council says it currently has 176 children on a waiting list for a PRU place, more than any other area.

Michaela Davies’s two sons, aged 6 and 8, who both have special educational needs, were both permanently excluded on the same day just two weeks before the end of last term from two schools in Warwickshire.

She claims to have been offered no provision of any sort for either of them.

“They’re just sat at home with no education. Where is the support for these children with disabilities?”

‘We can’t cope with the demand’

Philomena Cozens, the chief executive of the Keys Co-operative trust of three AP schools in Essex, says one of her schools took in almost 50 per cent more pupils than its official capacity of 115.

While PRUs would normally start a school year with small numbers of short-stay children, she says this year they will be “up to PAN” this month, with others still awaiting placement.

“I’ve never known anything like it. We still do a good job. But we can’t cope with the numbers of referrals.”

In Sheffield, the numbers excluded surpassed the PRU’s commissioned place numbers at Easter and the council agreed to increase capacity from 250 to 300.

While PRU numbers are down on pre-pandemic, Howell says it is now high waiting lists and high exclusion numbers. “The exclusions are happening at a faster pace than areas can keep up with.”

The latest DfE exclusions data, lagged to 2021-22, shows while permanent exclusions began rising after a pandemic lull, they were still lower than in 2018-19. But suspensions have rocketed.

Most councils were unable to provide exclusion figures for last year – but there were rises in 21 of the 22 that did.

Exclusions on the rise

Overall, the councils recorded a 61 per cent rise in exclusions between 2021-22 and 2022-23. Their overall exclusions figure was 50 per cent higher than in 2018-19.

Furthermore, council reports for Surrey, Lancashire, Essex and Bristol indicate rising permanent exclusions, while sources in Birmingham, Suffolk and Plymouth tell Schools Week of rising exclusions too.

For the first time, behaviour and exclusions are among the top three challenges cited by secondary school governors in the National Governance Association’s annual survey.

Many local authorities are responding by building new AP provision and specialist resource bases for schools. Some large trusts are opening their own AP.

But a briefing earlier this year by Schools North East warns that new AP being built in the region is expected to “reach capacity quickly” due to “large numbers of students coming out of mainstream”.

Cozens says pupils are also staying in provision longer because they are unable to get back into mainstream schools.

Her year 11 cohort were at the PRU for an average of three academic years – leaving her school without the capacity to offer short-term placements.

Creaking support services leave schools short

The most common reason (35 per cent) for permanent exclusion in 2021-22 was persistent disruptive behaviour.

A report out this week from the Who’s Losing Learning Commission found that last year children with special needs were four times more likely to be suspended and those with education, health and care plans (EHCPs) were 3.7 times more likely.

The DfE’s SEND and AP improvement plan admits that AP (including PRUs) “is increasingly being used to supplement local SEND systems”.

Cozens notes a rise in children with unidentified learning needs being excluded because mainstream schools were unable to get their needs assessed in a “timely fashion.

Almost half of children needing SEND support waited beyond the legal deadline of 20 weeks for an EHCP to be issued last year.

“When that’s left too long, very often the child makes a choice to be naughty rather than look stupid,” Cozens adds.

Sheffield’s school forum raised concerns that its PRU was “receiving children with special needs that shouldn’t be” there.

Its will now turn the facility into a “learning centre”, rather than “simply looking after” its cohort.

Budget cuts cause problems

Budget cuts are also hampering tackling behaviour issues, with slashed support services.

The notional SEND support budget of £6,000 per pupil, which has not risen since it was introduced 10 years ago, also “penalises inclusive schools at the expense of those less welcoming to children needing additional support”, says John Pearce, the president of the Association of Children’s Services.

Exclusions also have cost implications for councils; Lancashire’s predicted budget spend on excluded pupils almost tripled from £0.4 million to £1.1 million in 2022-23.

But there are fears that DfE’s plans to rein in councils’ spending, by reducing EHCPs and accommodating more children in mainstream, will only accelerate the pace of exclusions.

Cash-strapped Kent, where a recent Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman (LGO) investigation uncovered a backlog of 170 unanswered complaints over delayed SEND support, is now attempting closer collaboration between its PRU, inclusion, attendance and SEND services to “examine the correlation between pupils with SEN[D] and suspensions, and to set up robust action plans”.

Concern over illegal exclusions

PRU pupil numbers in 2021-22 (11,684) were almost double that of DfE data for permanent exclusions (6,500). Jenny Graham, director of research at inclusion charity the Difference, says this is a sign that exclusions are taking place via unofficial routes.

Ofsted said in December that part-time timetables are being used “too often” to manage pupils’ behaviour, sometimes as an alternative to exclusion.

DfE guidance in February warned schools against this, but Datalab analysis in June found 34,000 pupils could be on part-time timetables.

John Coughlan, the commissioner sent in by ministers to resolve failing SEND services in Birmingham, earlier this year found “unhelpful and even illegal practices” around “exclusions and part-time provision”.

In Wakefield, a recent council committee suggested “some schools” used “partial timetables as an alternative to exclusion, which could lead to misleading statistics”.

Analysis of Arbor data showed schools appear to be using the attendance C Code, partly used to indicate part-time timetables, 12 per cent more frequently than they were a year ago.

Trust-council clashes

The rise again in exclusions and lack of specialist provision is causing system issues, too.

Ofsted has highlighted what it says are high exclusion rates, including at schools belonging to the Outwood Grange Academies Trust, run by the incoming new chief inspector Sir Martyn Oliver.

But the DfE’s own behaviour tsar, Tom Bennett, says the inspectorate was “flat out wrong” for saying exclusions are “too high” at another turnaround trust, Astrea.

“If we can’t exclude when absolutely necessary, then we cannot keep children safe, or teach them in calm, dignified environments,” he says.

“Otherwise we force children who have been, for example, sexually abused, to share the school with their attackers, or bullies… Schools that exclude legally should be supported, not censured, for performing their duty to the children and staff in their communities.”

Every council has a fair access panel that helps to match pupils with school places outside the usual admissions round.

But local authorities lack powers to compel trusts to accept the panels’ decisions, and Pearce says trusts often arrange exclusions and managed moves outside that process.

That means schools that are “under capacity or [choose to] work with councils get disproportionately impacted”.

But trusts say they have little choice but to exclude to restore classroom discipline. Howell says with needs now “more extreme” he “understands why” all the kids in his PRU, City of Birmingham School, have been excluded.

In Plymouth, MATs have refused to share data around exclusions and have had to be compelled to do so by their regional commissioner.

Tudor Williams, Plymouth’s leader, says: “We called them out on that and they’re starting to give us the data – ironically, so we can kick them up the arse.”

Pearce describes it as “ludicrous that councils can’t access information about children’s education on their patch, when we’ve statutory duties to follow through. If that school is part of a MAT that doesn’t want to play, you’ve got to go through a convoluted process to get them to. You wouldn’t invent a system like that.”

Exclusions cited in serious case reviews

The prospects for children excluded from school are bleak. Only 4 per cent go on to pass their English and maths GCSEs, and half fail to sustain employment, education or training post-16.

Three serious case reviews in the past two years – held when a child or vulnerable adult dies or is seriously injured in circumstances involving abuse or neglect – cite exclusions as contributing factors.

A 2021 review into “Daniel”, who was shot in a revenge attack and had a leg amputated when 17, stated the “real problems” started four years earlier when anti-social behaviour led his recently academised school in Redcar and Cleveland to permanently exclude him under “‘new’ behaviour management procedures”.

He joined a PRU under investigation over its leadership, a failed managed move to another school and then tuition sessions, which were stopped because he was seen as “unlikely to pass his exams”.

Another two case reviews of young male stabbings (one fatal) in 2021 and 2022 also highlight school exclusions. One describes how things “quickly went wrong” for Harry in Wokingham after his permanent exclusion aged 11 left him outside education for a “number of months”.

Had a specialist placement been commissioned then, his mum feels his outcomes would have been very different. Instead he “drifted into criminality”, two years later being sentenced for a knife attack.

A group of parents in Brighton and Hove this week told the council how a lack of full-time alternative provision had led to a “disturbing situation” where children were “exposed to child criminal exploitation in the community”.

They said some children have been offered a “part-time package” that is “not sufficient to prevent the risk of negative behaviours in the community and child criminal exploitation. There is little aspiration for our children, and their future feels uncertain.”

Disagreement on the way forward

Mayor Sadiq Khan’s Violence Reduction Unit in London has drawn up an inclusion charter with councils and schools to bring down exclusion rates.

He has recruited Maureen McKenna, who oversaw a reduction in permanent exclusions after a similar scheme in Glasgow.

But Bennett says the decrease in exclusions is down to schools being told to stop using them, rather than reflecting an improvement in pupil behaviour.

The government’s first national behaviour survey in June found 50 minutes a day are already lost to dealing with poor behaviour.

A survey by the NASUWT union of 6,500 members published this week reveals what general secretary Dr Patrick Roach says is an “alarming increase in violent and defiant behaviour”.

Thirty-seven per cent of respondents reported physical abuse from pupils in the past 12 months, including furniture thrown at them, being bitten, spat at, headbutted, punched and kicked.

The Scottish government also this month hosted an emergency summit after reports of rising violence in its schools.

A recent UN report called for a prohibition of exclusions in UK primaries, with former children’s commissioner Anne Longfield saying this should be in place by 2026.

But a 2018 Teacher Tapp survey found 56 per cent of respondents strongly disagree with any ban.

Johnson says PRU heads remain “deeply concerned” about the growing number of children waiting for EHCP assessments or specialised provision, many of whom have “faced repeated exclusions”.

The government’s SEND and AP improvement plan proposed changes included a statutory framework for pupil movements, three-year AP budgets and cutting long-term placements.

But the bulk of the focus is on mainstream schools being more inclusive, which leaders say won’t work without more funding or better support services.

“While the SEND and AP green paper outlined a clear desire for support at the right time and place, it’s disheartening to see that this vision has yet to materialise for many children who find themselves waiting for provision,” Johnson says.

Amendment: We added exclusion data from two additional councils that responded shortly after the article was first published in our Friday digital edition and amended the copy accordingly

We also changed the Arbor data on the use of code E from 11% going to 15%, to 0.11% going to 0.15%

Fill up the PRUs and exclusively staff them with the CEOs and Executive Heads – who can use their amazing expertise and skills to stop letting the system leave behind these poor children and their families.

My son is in this position. Perm ex in year 11, 9 weeks ago for a one off incident. No history of bad behaviour . Been refused by schools. Pupil admissions are useless. Why are these schools allowed to say No? He gets an hour each week of English and maths and that’s classed as suitable, alternative education. The Fair access policy is not followed and he has become one of these forgotten children. I feel useless as I have tried everything and no-one is interested or bothered.